Mac History 85.10 - Welcome to Macintosh

The creation of the original Macintosh has been extensively studied and written about, not least by Andy Hertzfeld, but what happened after it launched? What was it like to own a Macintosh in the mid-eighties? How did users and developers adapt to the graphical user interface?

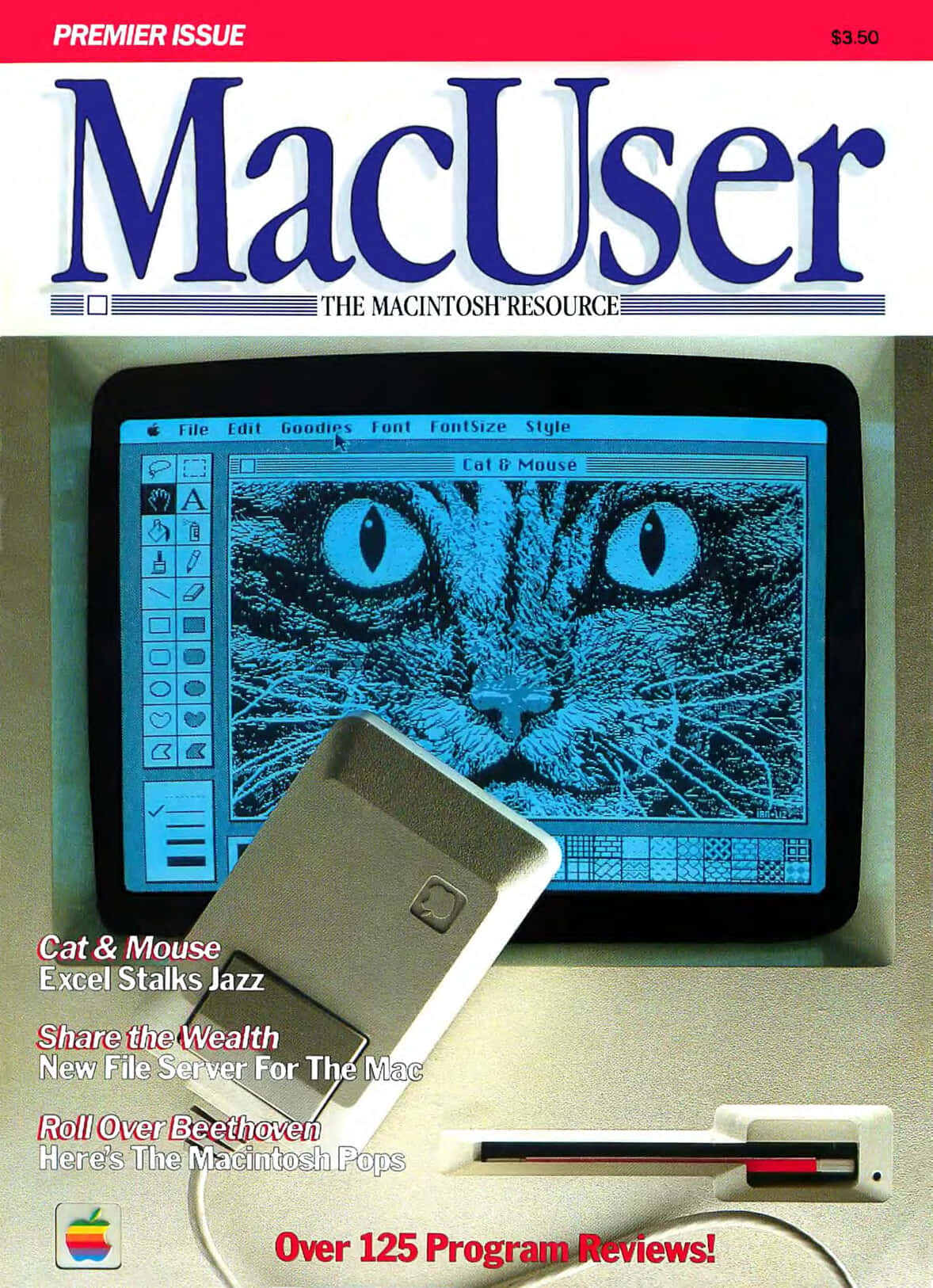

I intend to tell this story of the Macintosh through the pages of MacUser. I chose this magazine because of its broad perspective and entertaining writing style. It’s undoubtedly a nostalgia trip, but one with important lessons for today’s software and hardware designers.

Throughout the series, I have liberally linked to other blogs, magazines, videos, and even research papers to tell the story of this fascinating period and encourage you to run some of this software on an emulator or classic Mac.

This post is based on the first issue of American MacUser1 from October 1985 (85.10). We look at Macintosh models in 1985, before meeting ExperLisp, Microsoft Excel, and the Commodore Amiga. We go on a fantasy adventure, design some icons, and develop a desk accessory. Finally, John Dvorak asks if the Mac is too small to be seen as a serious business computer.

Macintosh Models in 1985

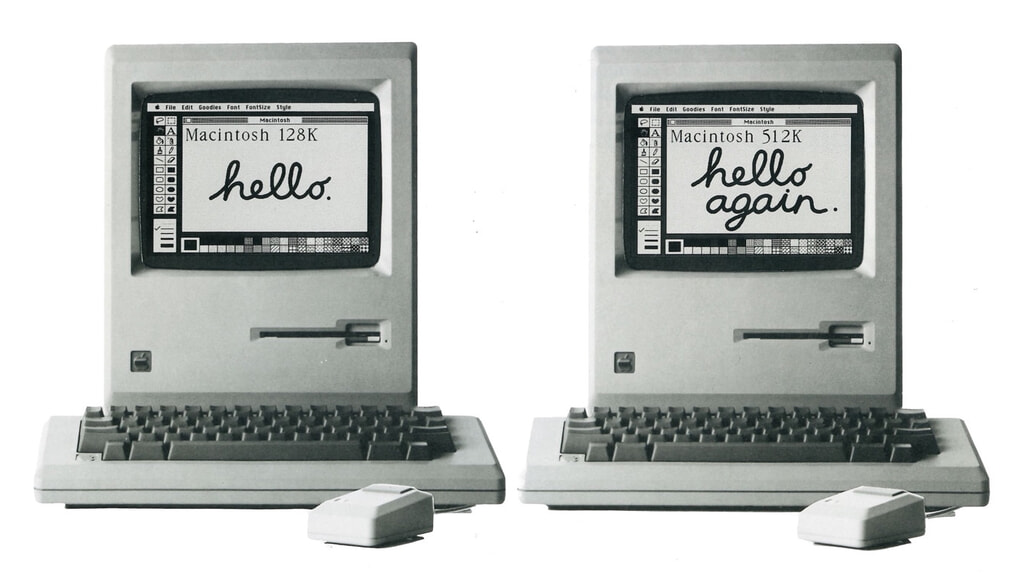

Before we open the magazine, it’s worth taking a quick look at the Macintosh models available in 1985. There were two: the Macintosh 128K and Macintosh 512K (the Fat Mac).

Both models feature an 8 MHz Motorola 68000, 512x342 black & white screen, 400KB 3.5" floppy drive, two serial ports, and a 64KB ROM. There is no hard drive option, neither SCSI nor ADB and definitely no expansion slots. Both models come with MacPaint and MacWrite; the only difference between them is the ram.

Emulating a Macintosh

If you want to emulate a 68K Macintosh, I recommend Mini vMac or Infinite Mac (runs in browser). You can download many of the software packages featured in this series from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

October 1985

Pick up your copy of MacUser October 1985 from the Internet Archive. Be aware that PDF page numbers do diverge from the magazine page numbers.

The Editor’s Desktop

Beginning with page 5, editor Neil Shapiro sets out the magazine’s philosophy:

The Mac is a tool and we are a magazine devoted to that tool. I suppose that we could write about the Mac as if it were a hammer… Or, we could do what MacUser does intend to do, we could teach you how to take that hammer and build a boat with it.

In Memorium: Andrew Fluegelman

On page 12, we learn of the sad death of Andrew Fluegelman in July 1985.

Andrew was simultaneously the editor of PC World and Macworld as well as developing the concept of shareware (which he called freeware).

The Digital Antiquarian has a fascinating series on the development of software distribution that begins with Andrew’s pioneering work: The Shareware Scene.

Programmers are born as much as made. You either feel the intrinsic joy of making a machine carry out your carefully stipulated will or you don’t; the rest is just details. Clearly Fluegelman felt the joy.

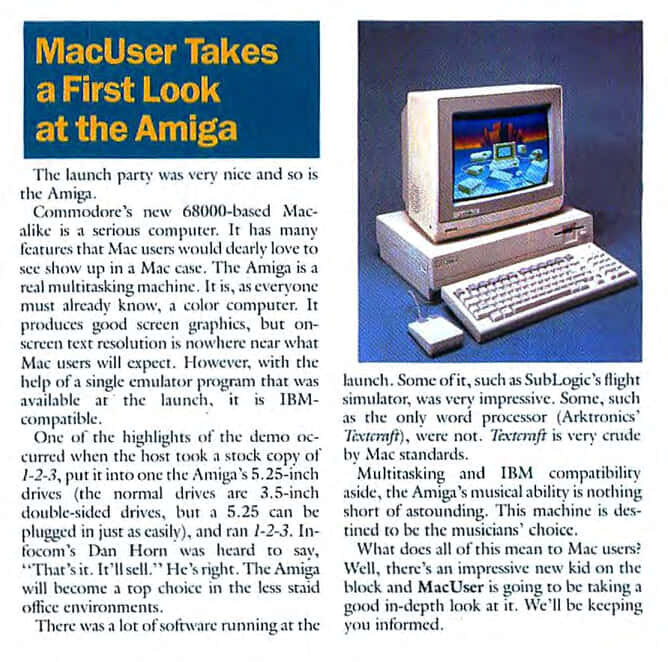

A First Look at the Amiga

Still on page 12, we get our first surprise; a report on the Amiga launch:

Commodore’s new 68000-based Mac alike is a serious computer. It has many features that Mac users would dearly love to see show up in a Mac case. The Amiga is a real multitasking machine. It is, as everyone must already know, a color computer. It produces good screen graphics, but on-screen text resolution is nowhere near what Mac users will expect.

Multitasking and IBM compatibility aside, the Amiga’s musical ability is nothing short of astounding. This machine is destined to be the musicians’ choice.

The first Amigas arrived at American dealers in October 1985. Blake Patterson (ByteCellar) describes the highs and lows of owning an Amiga in 1985.

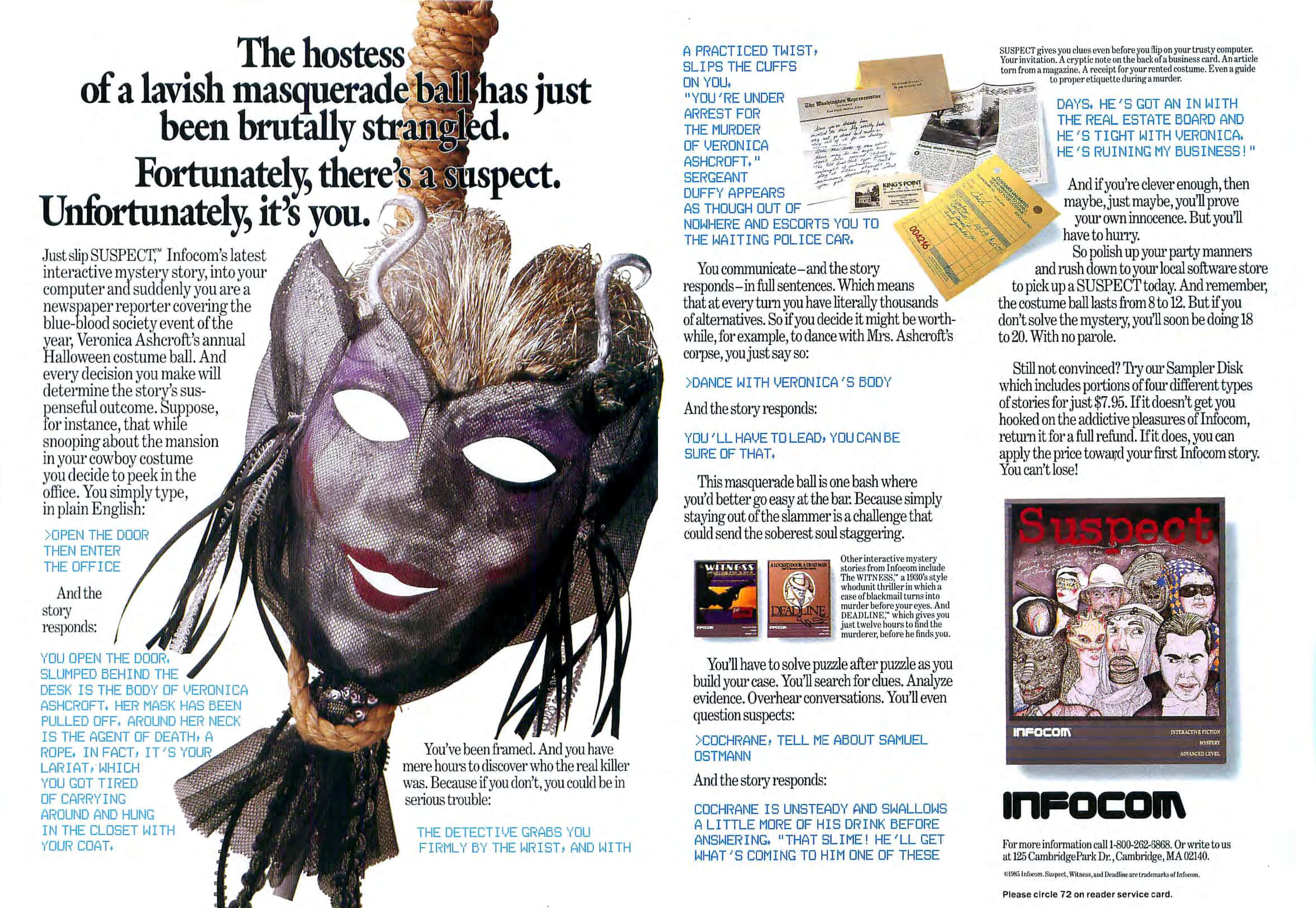

Suspect Advert

A few pages later, after page 14, we find a double-page ad from Infocom:

You open the door. Slumped behind the desk is the body of Veronica Ashcroft. Her mask has been pulled off. Around her neck is the agent of death, a rope. In fact, it’s your lariat, which you got tired of carrying around and hung in the closet with your coat.

The Digital Antiquarian is the place to read more about Suspect and its history:

An inevitable footnote to any discussion of Suspect must be the gala that Infocom held to promote it at the January 1985 CES. It was by far the largest party the company ever gave, yet another marker of the high-water point this period represents.

Text adventures sales were in decline by 1985, and Infocom would be sold to Activision the following year. However, a new generation of graphic adventures was around the corner with Deja Vu: A Nightmare Comes True (Jan ‘86).

You can download Suspect in its early Macintosh form or play it on any computer that can run a Z-code interpreter.

We have more text adventures in Novels of the Mind (Dec ‘85) and Leather Goddesses Of Phobos (Feb ‘87).

Software Isn’t Fragile

So far, we’ve had the Amiga and a game advert? What about serious Macintosh software? There’s plenty of that, starting with a column covering ExperLisp and software fragility on page 27.

ExperLisp is the first Lisp available for Macintosh. At present, it’s the only Lisp available for Macintosh. It costs $495. And it is incredibly buggy. Extraordinarily buggy. Even for Macintosh. Which is saying a lot.

Other languages let you write programs. Lisp lets you create worlds: vast nets of interconnected structures and routines. This takes a lot of memory. ExperLisp won’t deign to sniff at 128K machines. Ideally, you’d have four megabytes or so to romp in.

Even ExperTelligence admits that the language is “fragile.” What a great word. What a great connotation: if it breaks, it’s your fault! After all, it’s “fragile.”

“Hey, Buddy, watch it! It’s fragile, you gorilla! Jeez!”

Software isn’t fragile. Crystal and soap bubbles and hope and butterflies are fragile. If software doesn’t work, it’s not fragile, it’s flawed.

But let’s be honest: everything crashes at one time or another. Everything I use on a regular basis crashes every so often. MacPaint is the only exception. I don’t think MacPaint has ever crashed for me (thank you, Bill).

ExperLisp is just worse, that’s all. But it’s still wonderful.The best analogy is Zork. In Zork, you wander around trying to figure things out and dying frequently. ExperLisp is no different. You try to figure things out and die frequently.

If you like to hack, you’ll love ExperLisp.

I’ve got mixed feelings. I love Lisp. I hate crashing. $495 is too much for anything. I love Lisp. Where’s Philippe Kahn when you need him?

You’ve likely never used ExperLisp (I haven’t). But if you’ve developed for NeXTSTEP or Mac OS X, you’ve used Interface Builder. Interface Builder started life in ExperLisp. If you know where I can find a copy of ExperLisp, get in touch.

The Long View has an intriguing article on Macintosh Lisp software.

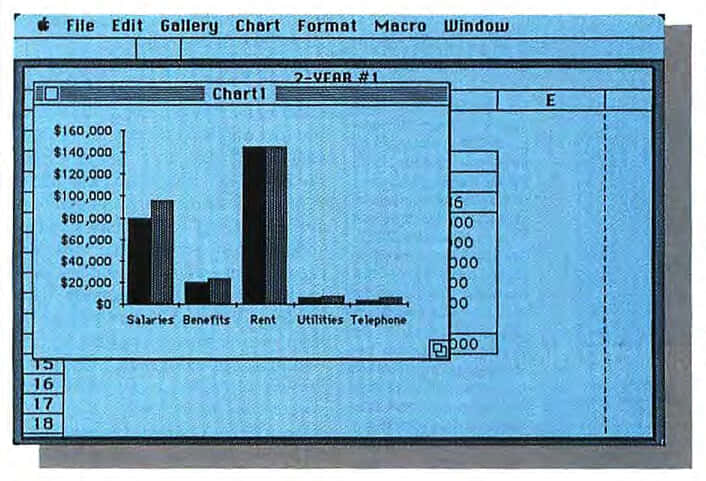

Microsoft Excel 1.0

When you first boot Excel the sheer size of the spreadsheet gives you the feeling of wide open spaces. 16,384 rows are numbered sequentially from top to bottom and 256 columns go from A, around the alphabet eight times, to IV. So the cell in the upper lefthand position is termed A1.

Microsoft Excel makes its first appearance on page 38. The Macintosh version is the original Excel; there was never an MS-DOS version. Lotus Jazz is also featured starting on page 32. You can read MacUser’s comparison of the two starting on page 43, but Mac users did not warm to Jazz, and it flopped.

You can read John Dvorak’s take in Whatever Happened to Lotus Jazz?

Once things settled down, Lotus had sold about 20,000 copies of Jazz, compared to Microsoft’s early sales run of 200,000 copies of Excel.

Learn about Execl macros (Dec ‘85), Excel charting (Sep ‘86), or see a visual history of Excel at the Version Museum.

For the early history of Excel, check out this video from Another Boring Topic:

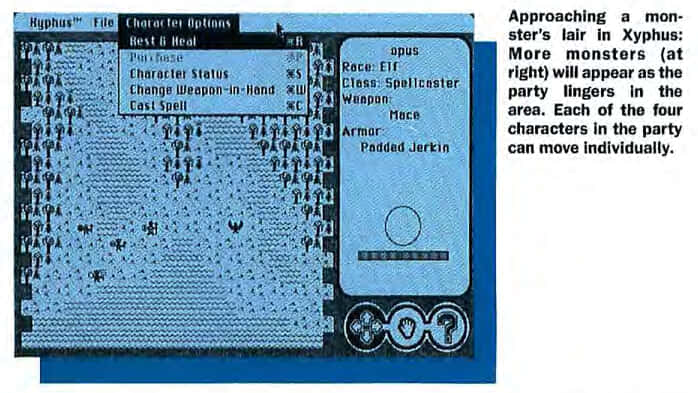

The Wizard Is In

The mid-80s Macintosh doesn’t seem well-suited to games, lacking colour and joystick support. However, that didn’t stop people from creating games for the platform. In this issue, MacUser dedicates a big feature to RPGs. Annoyingly, this feature is spread across three different parts of the magazine (pages 60-63, 124, and 144). I wonder how they did the layout for MacUser in 1985? When did they adopt DTP?

Xyphus might be the first RPG released for the Mac and runs in 128K. You can read the Xyphus manual (PDF).

Of all the role-playing games available for Mac users, Xyphus is the least intimidating, thanks to its sequential structure and icon control.

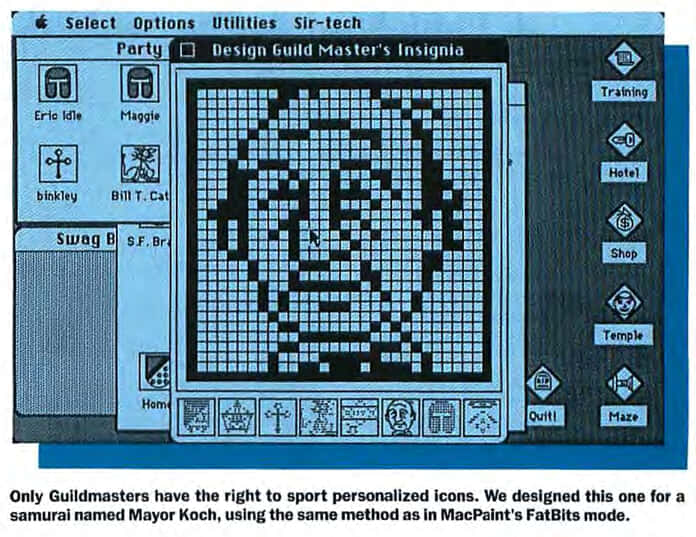

Sir-Tech’s Wizardry started life on the Apple II in 1981, but here it appears in a spruced-up Mac version:

There’s also a discussion of the different versions of Ultima, including the upcoming Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar:

The entire game can be changed, for better or worse, if your character behaves or misbehaves extremely. Since emphasis is placed on how you act, not just that you do something, this game scratches the surface of the next generation of role-playing games: those that reward or penalize characters for acting like they should (or shouldn’t).

The CRPG addict has several posts on Wizardry, including Wizardry: Won! (Seriously!)

See also: Rogue (Feb ‘86) and The Dungeon of Doom (Jan ‘87).

Mac3D Advert

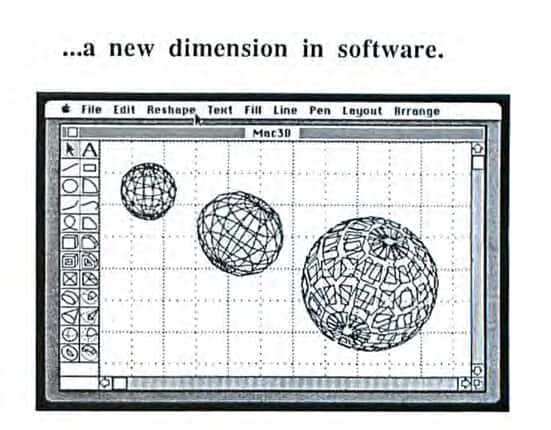

After page 70, we find an advert for Mac3D.

Use it to create technical or free form drawings and designs. Simply select from a palette of basic shapes and then stretch, flip, resize, reshape and/or rotate your drawing along any axis in three dimensions–much like you would shape a globule of clay and examine it in your hand.

Read a quick review of Mac3D 2.0 (Jan ‘87).

The Gourmet’s Icon Cookbook

Page 95 introduces ResEdit and explains how to create your own icons.

The land of icons lies deep, within your files. Getting there is not hard or dangerous if you have a good map and a knowledgeable guide.

We also get an insight into Macintosh files:

A Macintosh file is not like a file found on other computers. A Macintosh file can have two parts, each called a fork. One Is called the data fork, and the other is called the resource fork. The data fork can contain anything, and is not necessary in an application; the resource fork can only contain resources. A MacWrite document, for example, is mostly data fork information. MacWrite itself is resource fork information. A minimal Macintosh application must contain at least CODE resources.

Gourmet’s icons continue in the November ‘85 issue on page 122.

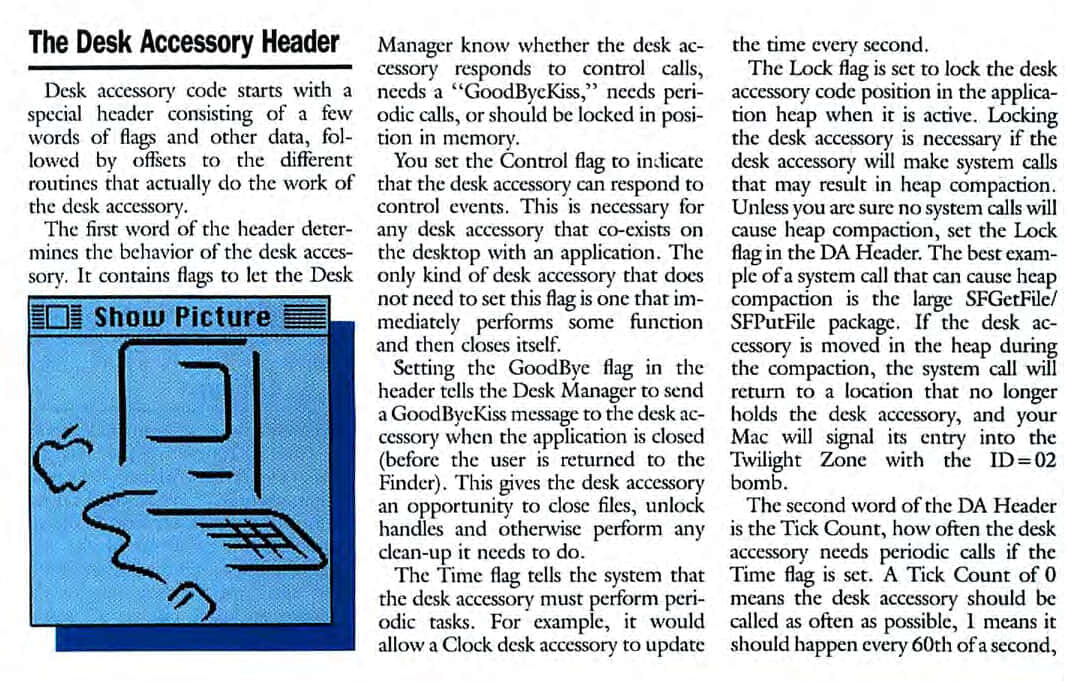

The Art and Craft of Desk Accessories

If designing icons is too tame, how about developing your own desk accessory on page 114? Desk accessories were vital in the early days of the Macintosh as you couldn’t run multiple applications at once.

Want to get in on goodbye kisses and all sorts of other wonderful Mac stuff? All you have to do is write a desk accessory, one of those innovative Mac concepts. And we’ll show you just how to do that using Apple’s MDS 68000 assembly language.

Yes, you read that right; MacUser is going to break out the 68000 assembler.

A desk accessory is a special type of device driver. The application communicates with the desk accessory via the part of the operating system known as the Desk Manager.

Alas, the small source text is hard to read from the PDF. I’ve tried to clean up a sample to give you a flavour:

; Find out the screen size from the Quickdraw globals

; Is it a Mac, a Lisa, or ?

; The Quickdraw global screenBits.bounds has the size

MOVE.L (A5),A0 ; Get pointer to Quickdraw globals

ADD.L #screenBits+bounds,A0 ; Add offset screenBits.bounds

LEA ScreenHeight,A1 ; Save screen height

MOVE.W bottom(A0),A1

LEA ScreenWidth,A1 ; Save screen width

MOVE.W right(A0),A1

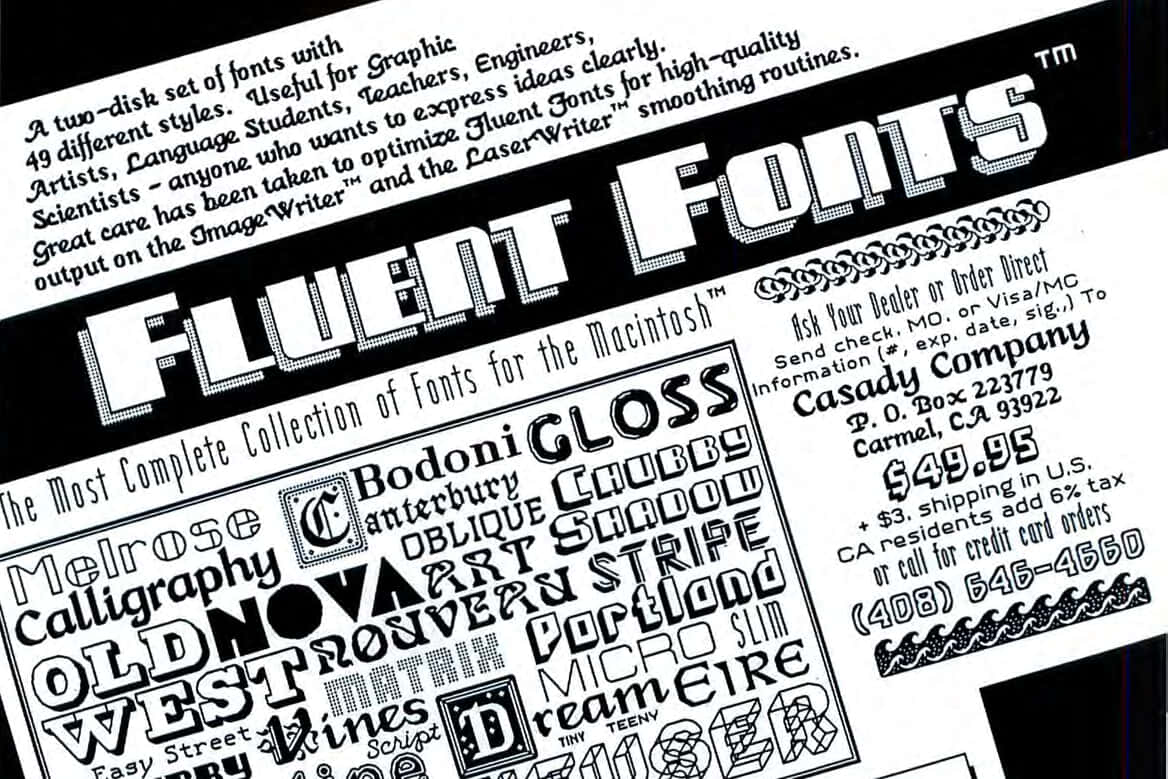

Fluent Fonts Advert

Vector fonts were a significant advance, but it’s hard not to love these early bitmap designs (after page 122). Plus, $1 a font sounds like an excellent deal.

Download Fluent Fonts or check out the Adobe System Type Library (Sep ‘86).

Ask a Hippo?

Before there was Google search or WolframAlpha, there was the Exotic Hippo Almanac. The advert (after page 144) claims: It understands English, thinks fast, and knows over 35,000 useful, intriguing facts.

The NY Times has a scathing take from 1987 (paywall).

The Devil’s Advocate

I associate John Dvorak with PC Magazine, but MacUser gave him a column from issue one. He doesn’t mess around (page 152).

The AT, for example, is big - it looks like a computer should look. It even has some lights on it. By contrast, the Mac looks like a kitchen appliance. Folklore has it that Steve Jobs demanded that the thing be designed to “look Like a Cuisinart machine.”

More than a few people are now recognizing the fact that the original Mac is too small to be perceived as the serious business computer Apple wants to sell.

IBM PC/AT photo by MBlairMartin under CC BY-SA 4.0

IBM PC/AT photo by MBlairMartin under CC BY-SA 4.0

Other Features and Reviews

- File Servers: The Macintosh Office’s Missing Link (page 54)

- The Check is in the Modem: Banking on Your Mac (page 68)

- Terminal Programs You Can Live With (page 74)

- Roll Over Beethoven: Three Musical Programs for Macintosh (page 84)

- T-Shirt Fantasy: Design Your Own T-Shirt (page 46)

- Balance of Power: Game Review (page 50)

- Get It Out Of Your System: Juggle Fonts and Desk Accessories (page 104)

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 85.11 travels to November 1985. We meet PageMaker and the Atari ST, then go shopping for hard disks. We take a MacDraw masterclass, disassemble software with MacNosy, and dive into the ROM with MS BASIC. We hear from Bill Atkinson and ask if Apple has lost its mystique. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏

Postscript: My Early Macintosh Experience

I didn’t own my first Mac until the late ’90s, but thanks to a school friend whose dad worked in the university computing department, I was lucky enough to use Macs during the 80s. I played Dark Castle, designed and printed flyers for our school fête (I spelt it “fate” and had to correct it with Tipp-Ex), and got to see postage-stamp-sized videos in QuickTime v1.

There is an earlier UK Edition from Dennis Publishing. You can download the first UK issue (July/August 1985) from Macintosh Garden. ↩︎