Mac History 86.02 - Rogue and 68K Assembler

This month, Neil Shapiro talks slots, the Apple Hard Disk 20 arrives with HFS, and we create a function key with 68K assembler. If that wasn’t enough, we take on slime monsters in Rogue, put your Mac in touch with the world, look at free software, and find a desk designed specifically for the Mac.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the February 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

February 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser February 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

If It Were Up To Me

Neil Shapiro has another strong editorial on page 9:

In the PC and general-interest magazines there is an abundance of hardware advertised; plug-in boards of every variety, shape, description, function and price. Why, if you’re willing to spend the money on the plug-in boards, you can actually turn the IBM PC into a worthwhile state-of-the-art computer.

Ads in Mac magazines, on the other hand, are almost exclusively software ads or feature such peripherals as hard disk drives, modems and printers. There’s a whole category of advertisers missing because there’s been a whole category of possibility missing from the Mac.

Slots, internal ports; call them what you will, the Mac doesn’t have any. Inside the clamshell-tight case beats a heart as inaccessible as Scrooge’s before the first ghost.

Apple has got to open the Mac.

Why? I don’t know why! But I remember when I first popped the lid off my Apple II in 1978 and looked at all the empty sockets on the motherboard. I had no idea what was ever going to plug into those things. Of course, that idea of slots turned out to be one of the cornerstones that the years of Apple II development were based upon.

I had a bit of a shock when the Macintosh was released with long screws with funny heads holding it together. This, I thought, could be a mistake.

Apple starred calling the RS-422 ports on back of the Mac “virtual slots.” Hardware designers, Apple said, would be using those ports just as if they were slots. So I decided to wait and see.

I waited. I saw. The ports didn’t take the place of slots. There’s not a whole industry connecting to them the way there are industries filling the slots in the Apple IIs (well, let’s not get into the IIc) and IBM PCs of the world.

Apple didn’t announce any slots in 1986 but come 1987, they’d go all out with NuBus in the Macintosh II (stay tuned for coverage).

Color. There are two kinds of color, and I think Apple should announce both kinds. The first is a color-capable Mac. So much has been said about color on the Mac that I don’t want to reiterate it all. I don’t feel color is critical, but I think it would be used if it were available.

Apple would also grant this wish in 1987, once again with the Macintosh II.

The second kind of color may seem silly at first — the color of the case. Already I have a bunch of friends moaning and groaning about the white cases planned; everyone I know seems to hate the color. How about some designer colors? That color choice might seem silly, but it’s really the very last conceptual thing separating the Mac from entering the real consumer marketplace. It’s worth a try!

As for Neil’s final wish, this didn’t come true until the arrival of the iMac in 1998. You can enjoy all iMac G3 colours from The iMac G3 Project at 512 pixels. The 13 colours are: Bondi, Blueberry, Lime, Tangerine, Strawberry, Grape, Graphite, Sage, Ruby, Indigo, Snow, Blue Dalmatian, and Flower Power.

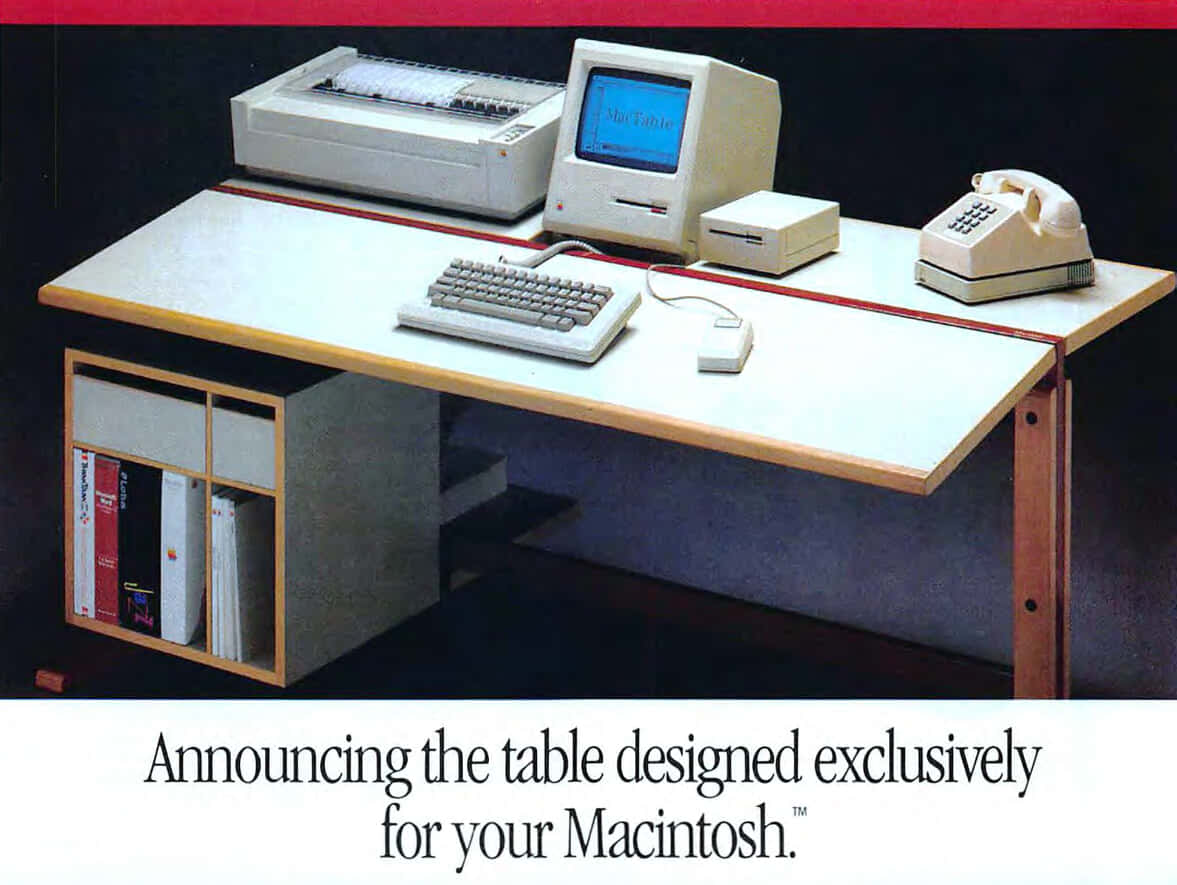

MacTable

The desk your Mac has been waiting for (page 21):

For more interesting furniture, check out MacStation II (Mar ‘86).

Clapp’s Law

The Macintosh Boundary is after your mom (page 29).

Wanting your mom is a noble desire. Anybody can get the nerds. Just give the nerds lots of memory (not that they need it), blinding speed, lots of pixels, and a universe of things to futz with, and they’ll be happy.

Remember the “Steve Jobs telephone analogy”? It goes like this: When computers are as easy to use as telephones, they’ll be as ubiquitous as telephones. I don’t think he said “ubiquitous” but I love that word.

Power User’s Manual

“86 things you’ve just gotta know!” starting on page 38:

Here’s a sample:

6 — Some disks, especially games and other commercially produced software, can only boot from the internal drive. So, don’t get too upset if the machine claims that a heavily copy-protected disk in the external drive is “unreadable.” Try it in the internal drive before tearing your hair.

19 — COMMAND, SHIFT and 3, pressed together, takes a MacPaint “picture” of what’s currently on the screen, if there’s enough disk space to store it. If not, a beep lets you known it can’t be done.

32 — The Font/DA Mover defaults to font mode when launched. To open directly into the desk accessory mode, hold down OPTION while launching the program.

39 — Running out of memory in an application? Reduce the size of the Clipboard as much as possible by copying a single letter into it. Do this procedure twice to ensure that you have removed the original clipboard contents.

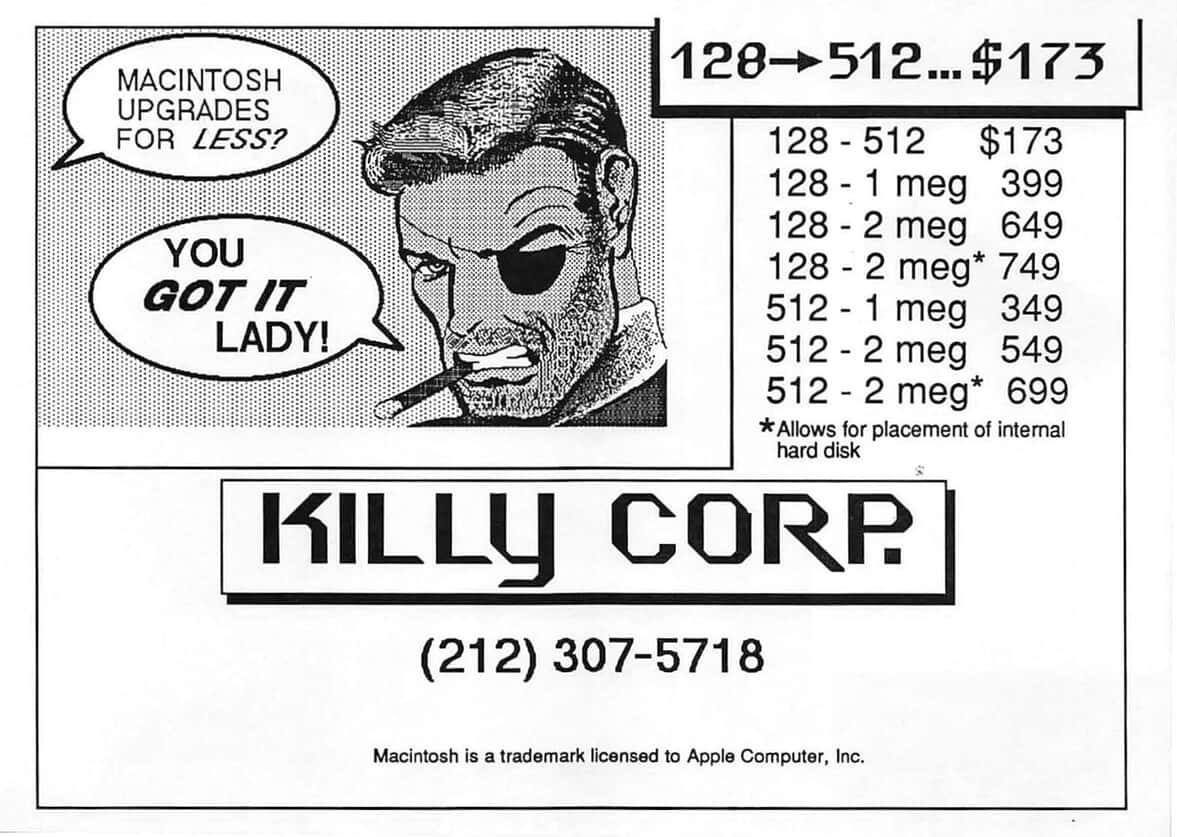

Killy Corp Advert

Memory prices were a significant constraint on computers in the mid-80s. Upgrade your 128K/512K mac to 1 megabyte for only $399/$349 (page 45).

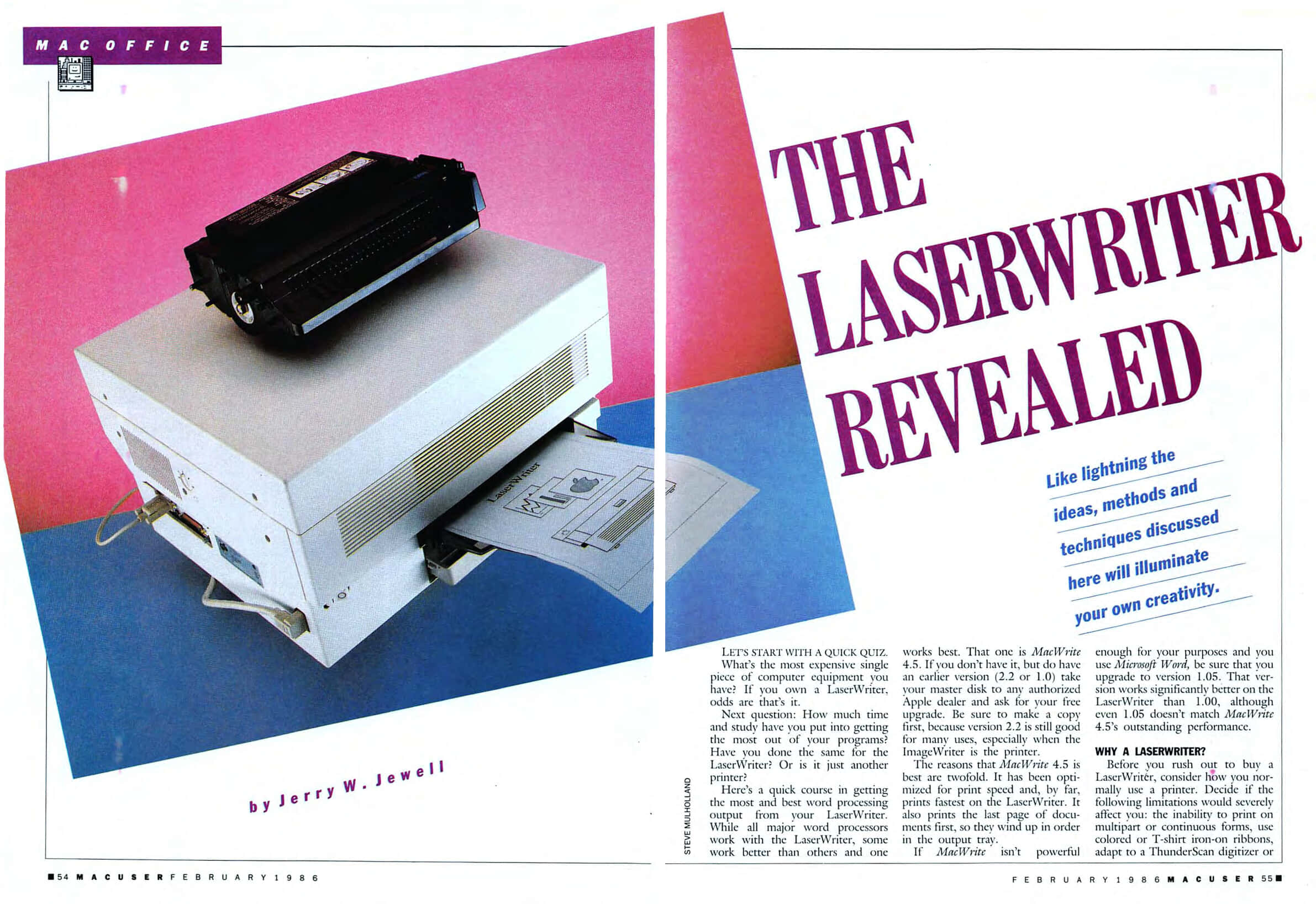

The LaserWriter Revealed

What’s the most expensive single piece of computer equipment you have? If you own a LaserWriter, odds are that’s it.

The feature on page 54 offers advice on getting the most out of your LaserWriter for word processing.

While all major word processors work with the LaserWriter some work better than others and one works best. That one is MacWrite 4.5.

- Always use the built-in fonts (Helvetica, Courier, Times and Symbol) for highest quality. Clicking on the “Font Substitution?” option will foul up page formatting if the document was not written entirely in Times, Helvetica, Courier, Symbol or some combination of these.

- Use simple fonts like Helvetica for large tables of numbers of informal documents.

- Formal fonts like Times are great for letterheads, reports and business proposals.

- Letters and correspondence should use the Courier font for the “typed look.”

The LaserWriter has a suggested retail price of $5,995. Add to this $100 for two AppleTalk connector kits, and more for paper, a spare toner cartridge and a stand, and the total cost will be around $6,500.

See also Printing the Light Fantastic (Jan ‘86), Plus the LaserWriter Plus (Mar ‘86), and Comet LaserWriter (Apr ‘86).

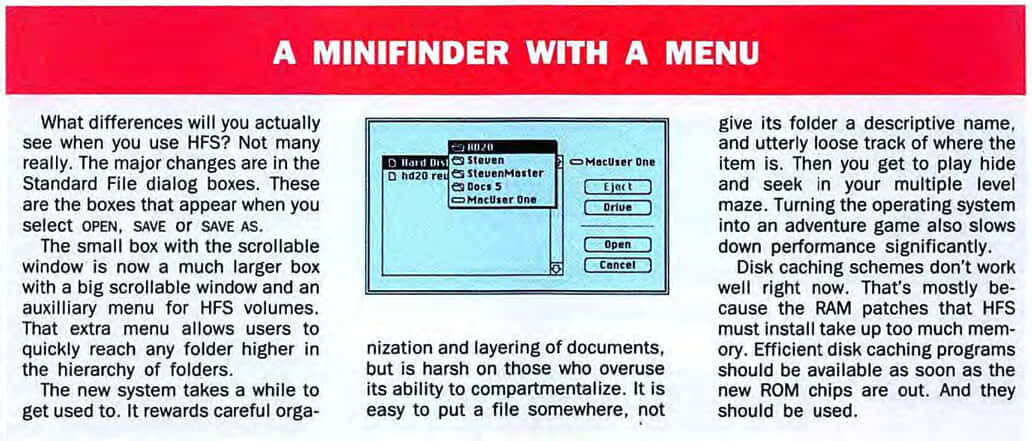

A Hard Mac is Hard to Find

“Apple’s new hierarchical file system opens new hard disk vistas for Mac users” on page 60.

The old file system, known as MFS or Macintosh File System, was not designed to handle the number of files that rapidly appear on even the smallest hard disks.

MFS is a flat or single-level system. All the files on a disk (regular or hard) are at the same relative level with respect to each other. HFS has multiple, ranked levels; that’s what hierarchical means.

The number of files that can be supported on an HFS disk is extremely large (well over 1000). While each subdirectory is still limited, there’s no reason to ever approach these limits.

Apple Hard Disk 20

The first hard disk to be designed to use the Mac’s new file system is Apple’s own Hard Disk 20. This 7-pound, 3-inch high unit fits neatly under the Mac. The rear view gets a bit tangled, since the unit adds its own connector (to the Mac’s external disk drive port) plus its own power cord to the clutter at the back.

Performance is good, but not spectacular. Most disk operations occur two to three times faster than they do when using floppies. Launching MacWrite from a half full disk takes approximately 11 seconds. That compares to about 25 seconds for a launch from a 3.5-inch disk.

Take a look inside the Hard Disk 20 (oldcrap.org) or read the manual (archive.org). Here’s an extract from the manual:

Now that you have 20 megabytes of storage, you can create hundreds, even thousands, of documents with many applications and store them all in one place. It’s like having a multidrawer filing cabinet instead of a cardboard box.

The Hard Disk 20 connects to the Mac 512K floppy drive port with a pass-through for an external floppy drive. However, SCSI quickly made this approach obsolete: see the Mac Plus launch (Mar ‘86).

See also: The Joy of Hard Driving (Jul ‘86) and Harder and Faster (Sep ‘86).

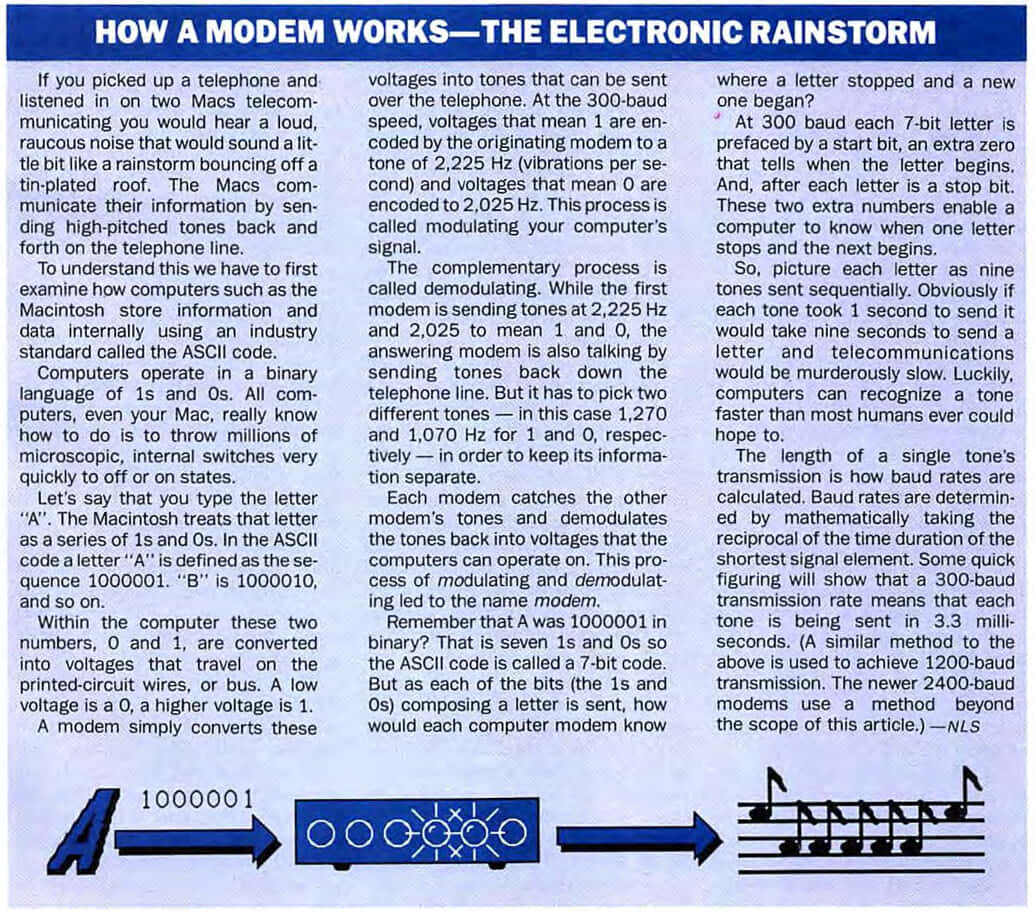

The Modem is the Message

“Put your Mac in touch with the world” on page 74:

Once that first connection is made (see “Your First Connection,” MacUser Vol. I, Issue 3, p. 84), it’s easy to get hooked on telecommunicating and want much more. Calling up your friend with a Mac isn’t enough. You know there’s more out there.

Here we’ll take a first-time explorer through the jungles of telephone lines and expose the hidden mysteries of one national database, Compuserve. The procedures are very similar to those used by both The Source and Delphi, so a new telecommunicator should be able to use this guide to find the way into any of the three services with little difficulty.

Messages can be sent in several ways. A full electronic mail system exists for private messages to individuals. In addition, open messages can be left on bulletin boards and forums. To leave a message, type out what you want to say in your word processor before going on-line. Save it as a text-only file. Then access CompuServe and find the area you want, say a section in MACUS. “Upload” the file by typing L after the function prompt. Reading messages that other people have left is accomplished by typing R.

See also: Talking Heads with VMCO (Dec ‘85).

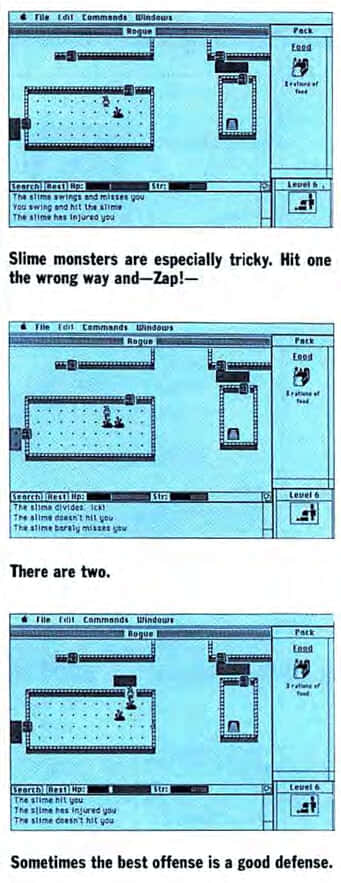

Rogue

“Gloria the great, dungeon explorer extraordinaire, is dead, struck down in her prime by a slime monster” on page 86.

Rogue is the first game of its kind on the Mac: an action-oriented dungeon exploration game in which the object is to kill as many monsters, grab as many treasures, and descend as many levels as possible before the inevitable end comes.

Rogue won’t win any awards for its strategic complexity or lightning-fast action. But it is the kind of game that draws players back for “just one more,” tantalizing adventurers with the possibilities of getting just one level further into the dungeon or discovering just one more type of monster. Players looking for a game that offers lots of replay value and simple, no-frills fun will enjoy spending some time with Rogue. After all, there’s a little bit of larceny in all our hearts.

Wikipedia has a solid article on Rogue and its history.

See also: Fantasy Role-Playing Games (Oct ‘85) and The Dungeon of Doom (Jan ‘87).

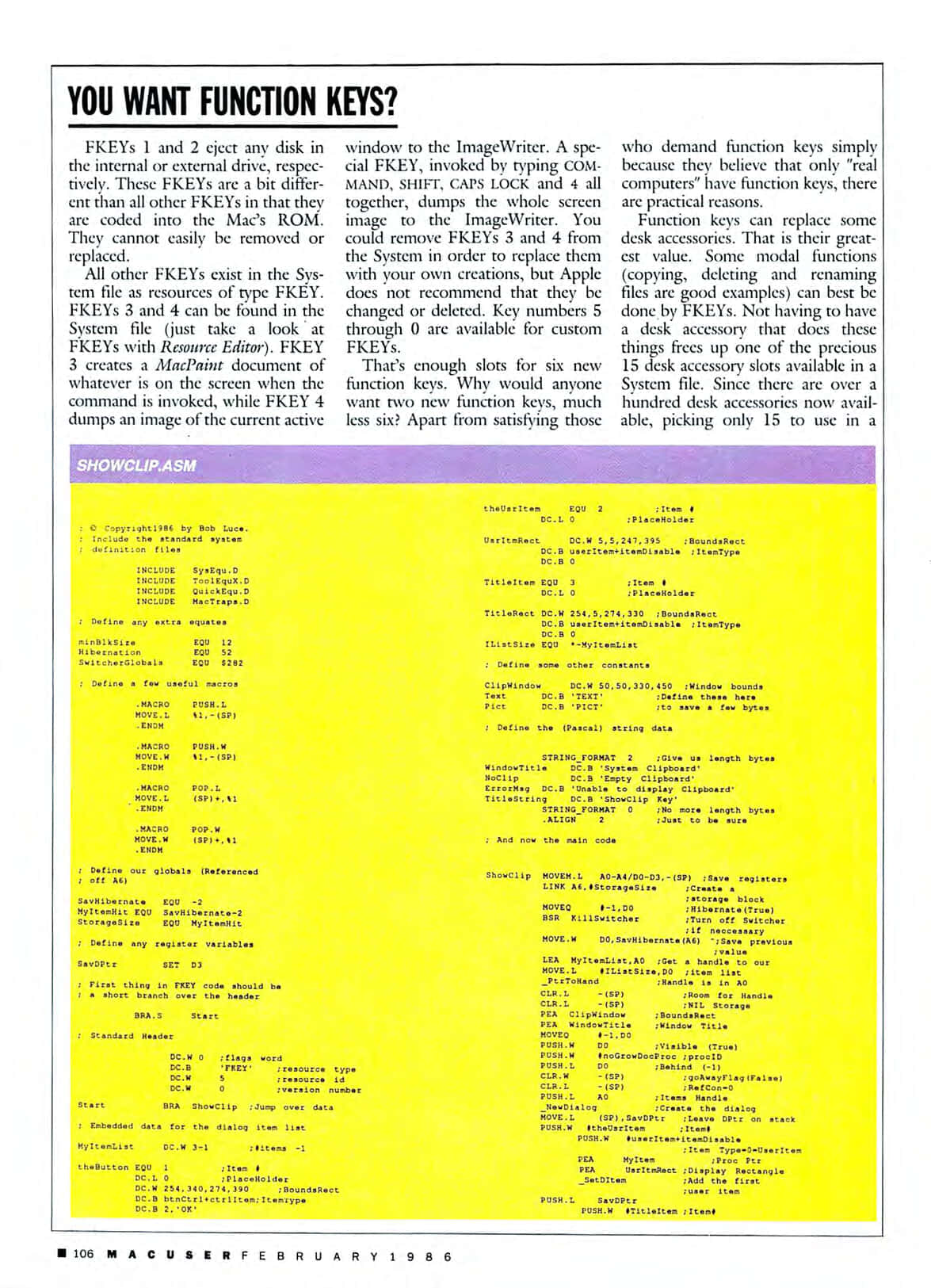

Function Keys? You want Function Keys?

MacUser continues its run of interesting programming projects. We break out the Macintosh Developer System (MDS) and 68000 assembler again, this time to create a function key (page 104).

My mother, an inveterate hacker if there ever was one, claimed that function keys were the cure for almost everything.

There are even a few function keys in the Mac. They’ve been there all along. While they are not physical keys, they are easy to get to. Simply type COMMAND. SHIFT and a number between 1 and 4 to access one of the Mac’s function keys.

FKEYs 1 and 2 eject any disk in the internal or external drive, respectively. These FKEYs are a bit different than all other FKEYs in that they are coded into the Mac’s ROM.

FKEYs 3 and 4 can be found in the System file (just take a look at FKEYs with Resource Editor). FKEY 3 creates a MacPaint document of whatever is on the screen when the command is invoked, while FKEY 4 dumps an image of the current active window to the ImageWriter.

FKEYs are relatively simple programming projects. They are good places for beginners to get their feet wet. We’ll show you how you can write your own FKEYs by describing what you need to know and giving you MDS source code for a sample FKEY called ShowClip Key.

To get the most from this article, you should be familiar with Apple’s MDS 68000 assembly language and have a copy of Inside Macintosh. To install ShowClip Key or your own FKEY into a System file, you’ll need Resource Editor or a new product by one of the authors of this article (Bob Luce) called FKEY Installer.

ShowClip Key is written in MDS 68000 assembly language, and should be easily adaptable to almost any compiled high level language. ShowClip Key simply draws any text or picture that is currently on the system Clipboard. It was written to demonstrate methods of overcoming some limitations placed on FKEYs, as well as their overall structure. Several fundamental Mac concepts are also demonstrated, from how to draw a picture in a window, to how to implement your own useritem in a custom dialog box. If a desk accessory can be likened to a “guest in someone else’s home,” then an FKEY might be described as an obnoxious guest who eats and runs.

If you want to give this a go, you can find the original Inside Macintosh courtesy of VintageApple.org.

Open to the Public

“Find your way through the maze of noncommercial software with this handy guide to the classics” from page 110.

Here’s a selection:

- PRAM - Utility: Sets default font, boot drive, etc.

- ProCount - DA: Counts words In any text file

- Big Ben - DA: Put the Tower of London on your desktop

- Catalogger - Utility: MS-BASIC program to catalog your disks

- Dr. Who Finder - Finder: Set of resources for a Dr. Who Finder

- UnWordstar - Utility: Converts WordStar files into MacWrite files

- Resource Editor - Utility: Apple’s Resource Editor

- Bubble Sort - Utility: A very fast bubble sort

- RAMstart - Utility: A full-featured RAM disk

- Uriah Heap - DA: Shows contents of heap area of memory

- Dungeon of Doom - Game: One of the best real-time adventures

See also: In Memorium: Andrew Fluegelman (Oct ‘85).

Programming Adverts

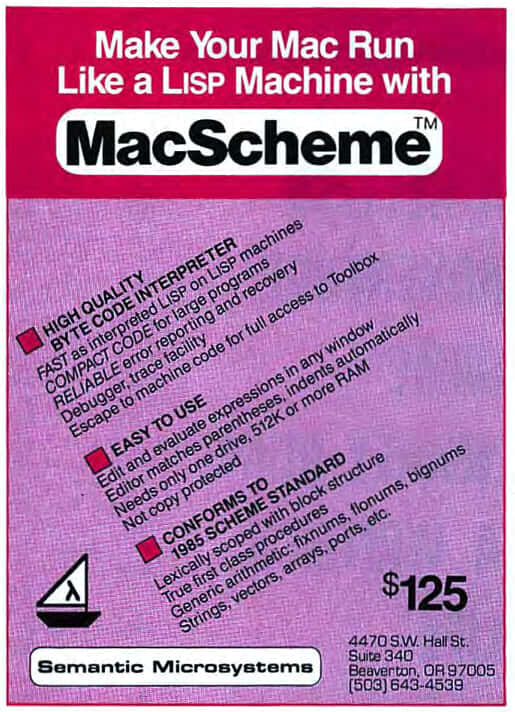

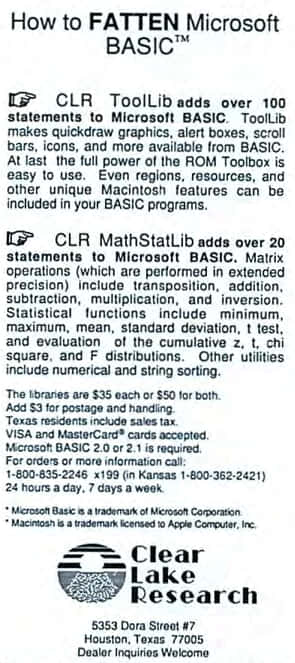

A couple of programming adverts caught my eye on page 139:

I’ve not been able to find a copy of MacScheme, but there is an extensive MacTech article Programming a Text Editor in MacScheme+Toolsmith (archive.org) from January 1987.

You can find an ediotorial on ExperLisp in Software Isn’t Fragile (Oct ‘85) and The Long View has an intriguing article on Macintosh Lisp software.

CLR’s software is reviewed in Beyond Bare BASIC (Jul ‘86). BASIC was a serious programming tool in 1986; see The Great Language Face-Off (Jan ‘86).

Other Features and Reviews

- Get The Picture - Business Filevision: new vistas in databases (page 46)

- The Paper Chase - Office paperwork was never so easy (page 68)

- First Draft - MacDraft: graphic power and some rough edges (page 80)

- If Mice Had Wings - Three flight simulators let you soar high (page 92)

- BASIC: A Dip Into The ROM, Part 4 (page 96) - started Nov ‘85

What’s Next?

The Macintosh Plus is the focus of our sixth issue A Macintosh History 86.03. Did Apple finally get it right? We also visit COMDEX ‘86, play chess and MazeWars, and discover why developers are switching to C. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏