Mac History 86.03 - Macintosh Plus: Packed With Power

The Macintosh Plus is the focus of our sixth issue. Did Apple finally get it right? We also visit COMDEX ‘86, get down to businesses with databases, play chess and MazeWars, and discover why developers are switching to C.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the March 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

March 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser March 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

Macintosh Plus: Packed With Power

Let’s jump straight into the Macintosh Plus coverage on page 39.

What Was

The first Macintosh was never the computer that Apple expected it to be. It did spark a revolution and a new generation of personal computers, but it never made it in its intended market. Instead of selling into the corporate offices of the Fortune 1000, Macintosh found a place among entrepreneurs, small business people, and people in the arts.

Instead of serving as a front end to a Lisa-based network, Mac became the cornerstone of Apple’s 32-bit product line. And instead of appealing to an audience content with the low-end capabilities allowed by its 128K RAM, the Mac has been devoured by users who want easy and fast access to the information revolution.

What Is

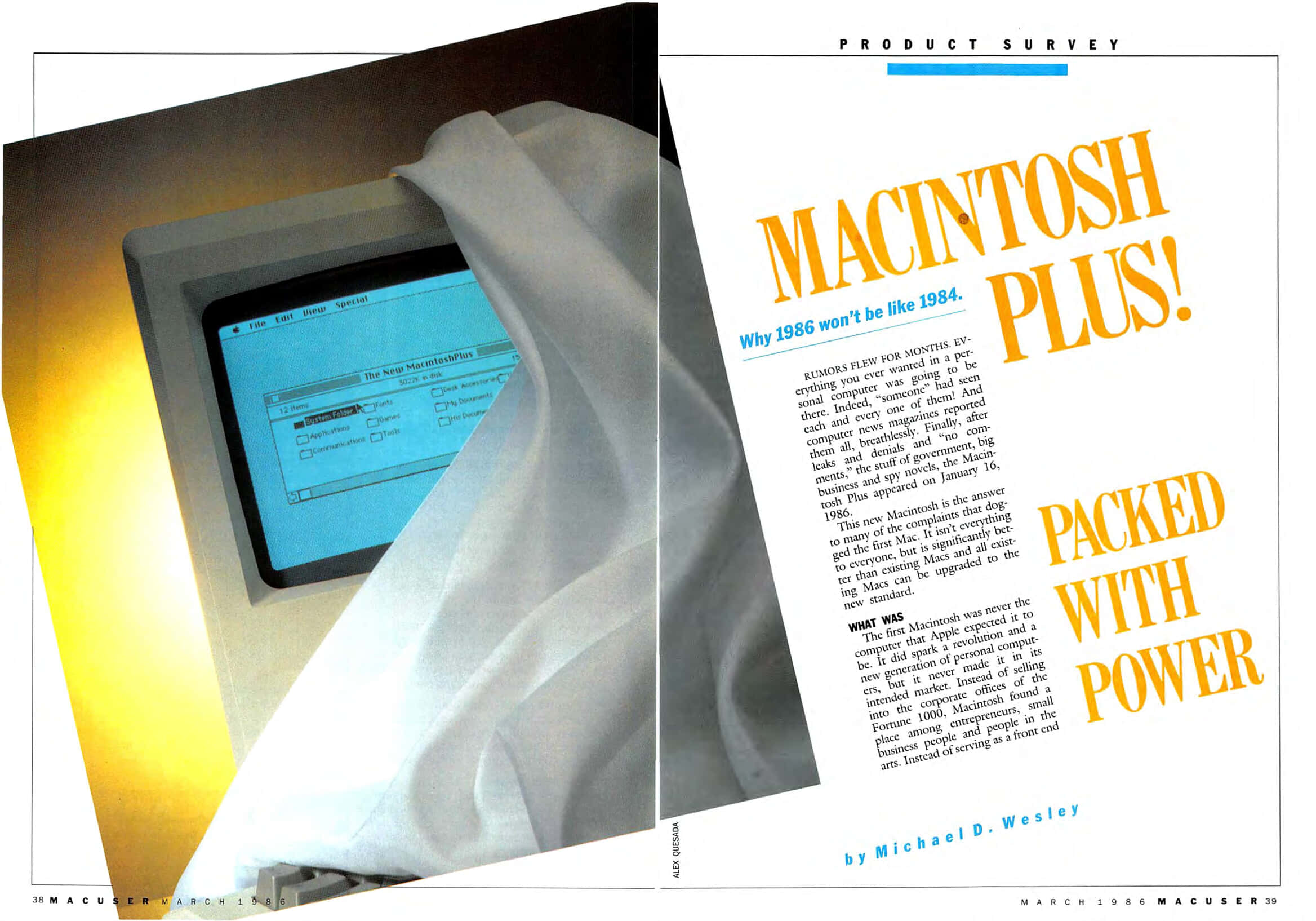

The basic concepts of the Macintosh Plus are enhanced speed, storage and expandability. These concepts are expressed in increased user and system memory, revised and improved System software, larger capacity disk drives, new interfaces, a new keyboard and an upgrade path for existing Mac owners (see The Road to Mac Plus - page 96).

Taking advantage of 256K-bit RAM chips, the Macintosh Plus comes with one megabyte of RAM on its digital (or logic) board. Everything on the logic board of the Mac Plus is soldered into place for the sake of reliability, except the RAM and ROM chips, which are socketed to allow easy upgrading.

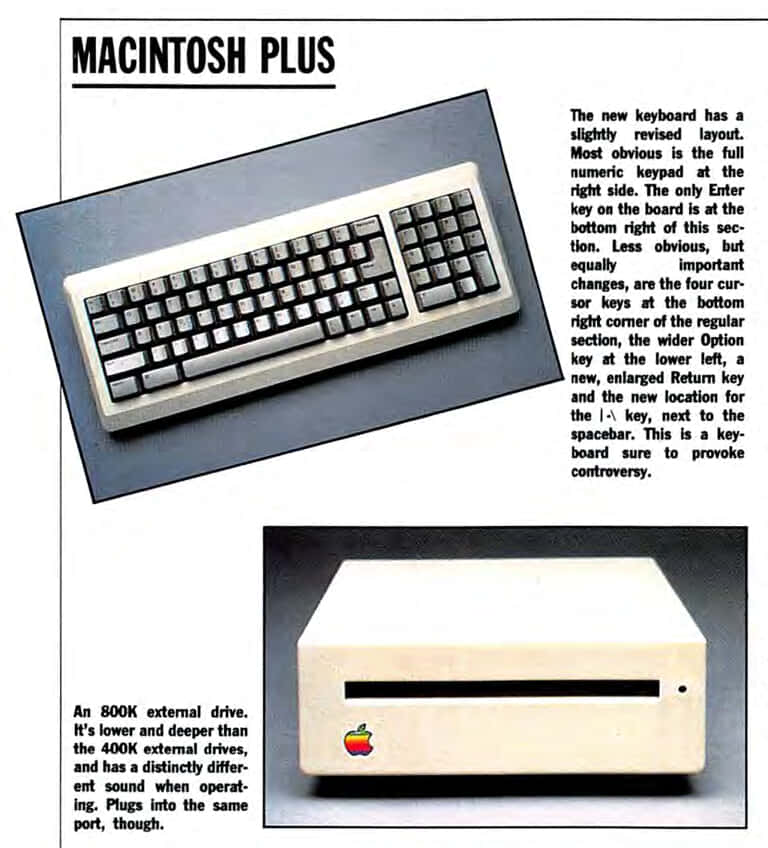

Macintosh Plus will be shipped with the long awaited, double-sided internal disk drive. The new drive can store up to 800K of information, compared to 400K on current Mac drives… Disk access is twice as fast on the new drives, so users can realize as much as a 30% increase in overall speed of operation.

The keyboard of the Mac Plus is a clear sign that Apple has responded to user demand. Many Mac owners have felt frustrated by a lack of a numeric keypad… The Mac Plus keyboard also includes four cursor control keys that allow movement within applications from the keyboard instead of with the mouse.

The final major difference between the Mac Plus and the standard Mac is the inclusion of a new port. The Small Computer Systems Interface (SCSI, or “scuzzy” interface, as it is frequently called) is an industry standard used for hard disks and other peripherals that require high transmission speed.

Mac Plus internals photo by Cody Logan under CC BY-SA 4.0

Mac Plus internals photo by Cody Logan under CC BY-SA 4.0

What to Do

Macintosh Plus is a significant improvement, and reflects the kind of market understanding many hoped to see after Apple’s reorganisation. Although the Mac Plus still does not have slots, Apple still plans to develop its future products along two design paths: “compact” or closed, like the Macintosh and the Apple IIc, and “expandable” like the Apple IIe.

The Mac Plus, with its greatly enhanced speed and capabilities, will be attractive to business users who have so far resisted the Mac. It will also be attractive to current users who need its power.

Plus vs 512K

While superficially similar to the original Macintosh, the Plus was a significant upgrade:

| Feature | Mac 512K | Mac Plus |

|---|---|---|

| Launched | Sep 1984 | Jan 1986 |

| CPU | 7.8 MHz 68000 | 7.8 MHz 68000 |

| Display | 512×342 Mono | 512×342 Mono |

| Ram | 512K | 1M |

| Ram Expansion | N/A | 4M (SIMM) |

| ROM | 64K | 128K |

| Floppy Drive | 3.5" 400K SS | 3.5" 800K DS |

| HFS Support | No | Yes |

| SCSI Port | No | Yes |

| Serial Ports | D-type | Mini-DIN |

| Expansion Slots | No | No |

| Numeric Keypad | No | Yes |

| Latest OS | System 4.1 | System 7.5.5 |

Pricing

Apple introduced the Mac Plus at $2,599 (equivalent to $5,300 in 20201), less than the $2,799 mentioned in MacUser. At the same time, the Mac 512K was reduced to $1,999, and the Mac 128K was discontinued. The Mac 512K seems poor value, but unlike the 512K, the Plus didn’t include MacWrite and MacPaint ($125 each).

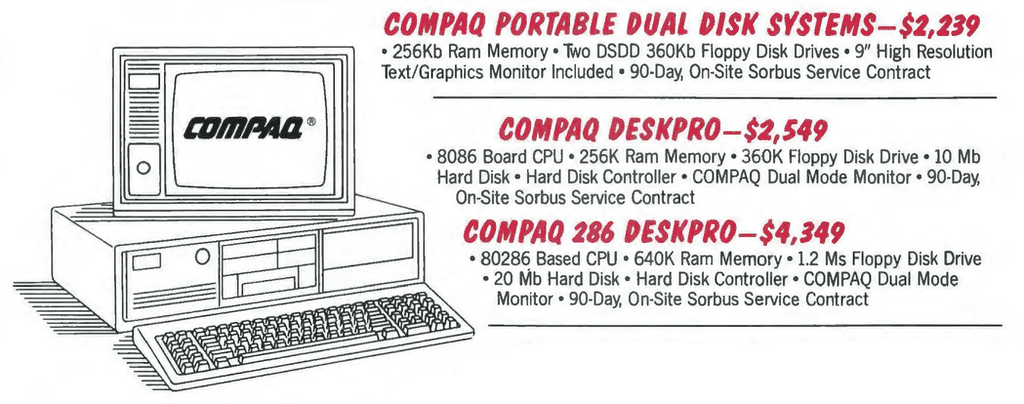

To put Apple’s pricing in context, I looked at Byte Magazine from March 1986. You could buy an XT clone for under $1,000, but an IBM or Compaq system costs significantly more, albeit with a hard disk included.

The Definitive Compact Macintosh?

Mac Plus photo by DualD FlipFlop under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Mac Plus photo by DualD FlipFlop under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Plus retains everything great about the original Macintosh while fixing its most important shortcomings: more (and upgradable) memory, 800K floppies, SCSI expansion, support for HFS. And Apple listened to users, expanding the keyboard with numeric keypad and cursor keys.

On the negative side, the Plus did nothing to tackle the lack of expansion slots and colour. Fixing these limitations required a different sort of computer, which Apple would deliver with the Macintosh II. More reasonable criticisms concerned the continued lack of fan and high price. The Macintosh remained a seriously expensive computer “for the rest of us”.

To quote John Gruber, the SE/30 might be “the pinnacle of the original Mac hardware design”, but the Plus best embodies the compact Macintosh to me. A machine that buttressed the Macintosh line for almost five years and laid a solid foundation for what was to come.

Emulating the Mac Plus

You can emulate the Plus courtesy of Mini vMac by Paul C. Pratt. The Plus is ideal for experimenting with the classic Mac software featured in this series, supporting System 3 to 7.5.5. You can also run Mini vMac in a browser thanks to Infinite Mac.

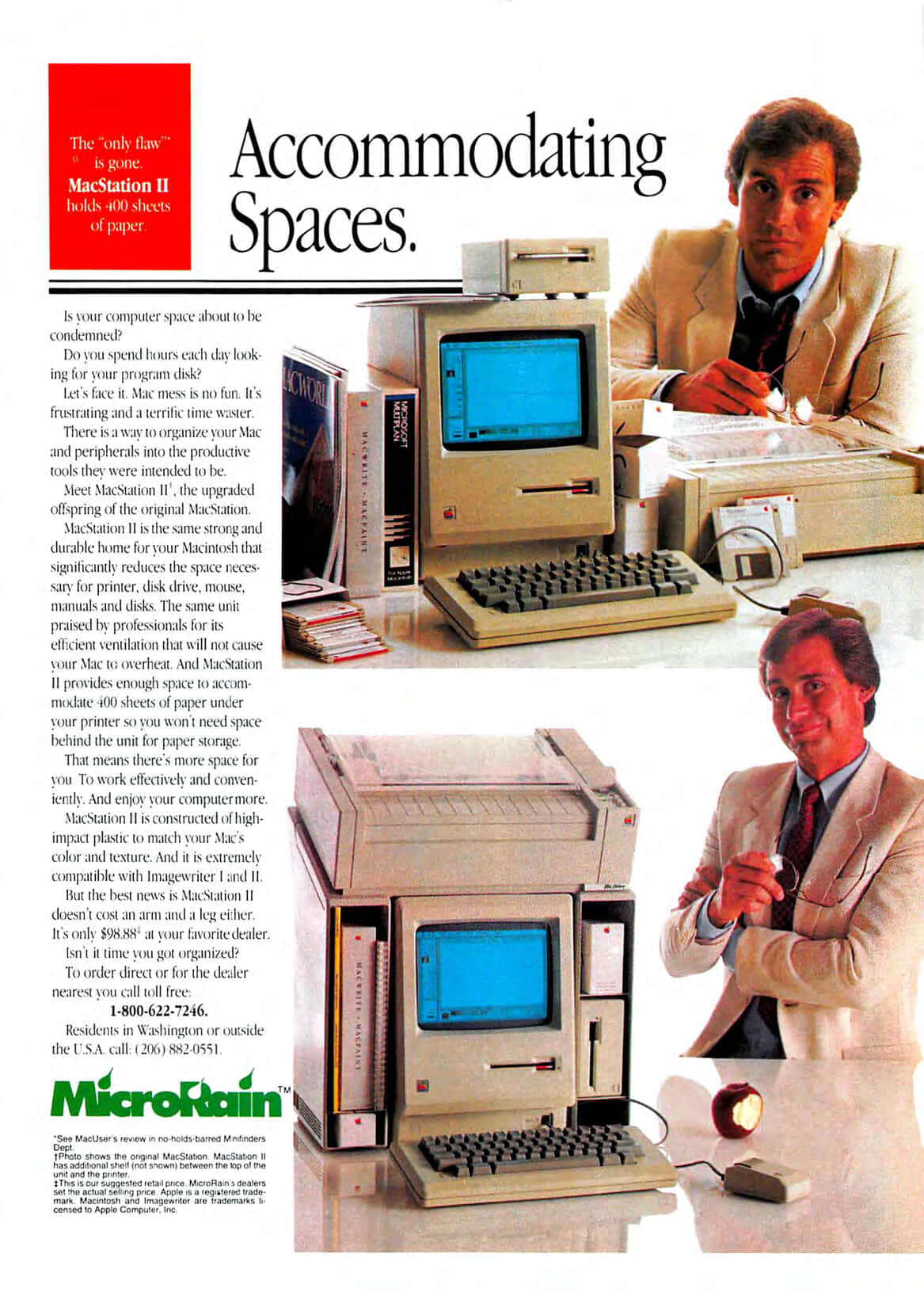

MacStation II Advert

Returning to our regular coverage, we begin with an advert for the MicroRain MacStation II on page 12:

Check out the MacTable (Feb ‘86) and find the MacStation II among The Strangest Classic Mac Peripherals I Have Ever Seen (vintagecomputing.com).

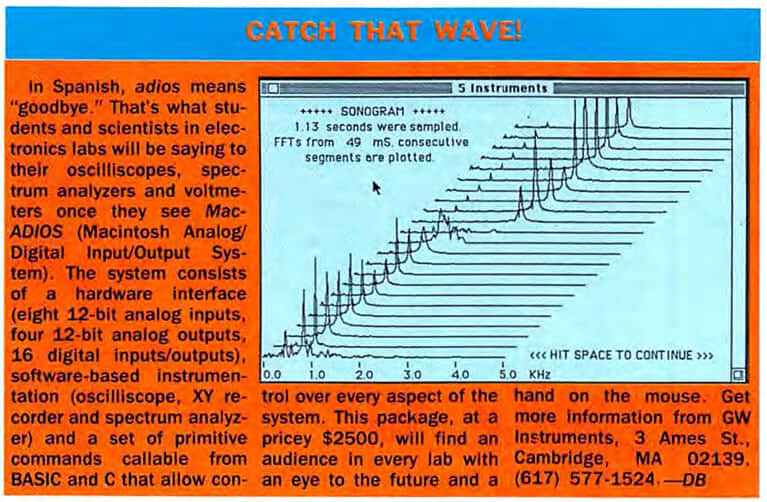

Catch That Wave!

Marc Andreessen famously wrote Why Software is Eating the World (WSJ), and MacUser shares the sentiment with ADIOS (page 18).

In Spanish, adios means “goodbye.” That’s what students and scientists in electronics labs will be saying to their oscilloscopes, spectrum analyzers and voltmeters once they see Mac-ADIOS (Macintosh Analog/Digital Input/Output System).

It’s 2022, and I still own and use a dedicated oscilloscope and suspect most electronics engineers do too, but my logic analyser works over USB with my Mac.

COMDEX Exposed

Michael D. Wesley goes to COMDEX ‘86. Turn to page 25 to read about Apple’s booth, expert systems, and the companies working on optical drives.

COMDEX is the stuff of legend: the excitement of new products; the glamour of emerging companies taking on the big boys; the insanity of aftershow parties where all the deals are really made; the lure of the world’s biggest job market for computer people; and the curious debut of new products that will never exist in production form.

Once I had entered the convention center, one of six display areas for products, I found it difficult to maintain the same awed posture that fit so comfortably in anticipation. This COMDEX was big and brash, but decidedly lacking in excitement, wonder and carnival showmanship. Most of the Macintosh products on display were showcased in the Apple booth, with products for all Apple models sharing the space.

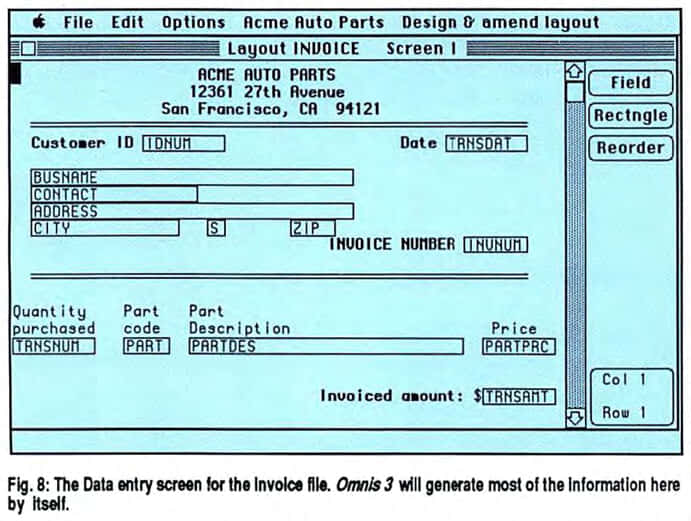

Databases

Databases were a common topic in these early Mac magazines. Databases in this context are more akin to FileMaker rather than backend server applications. MacUser looks at the practical applications of two such tools, starting with Omnis on page 42.

Meaningful Relationships

What can Omnis 3 do? Here, we’ve set up a complex problem that cries out for a relational database solution. The task will be to put together a system to help manage many business functions in a small auto parts store, Acme Auto Parts, including inventory of parts, customer balances and invoicing. The system should be developed in a very short period of time.

On page 48, it’s the turn of Helix.

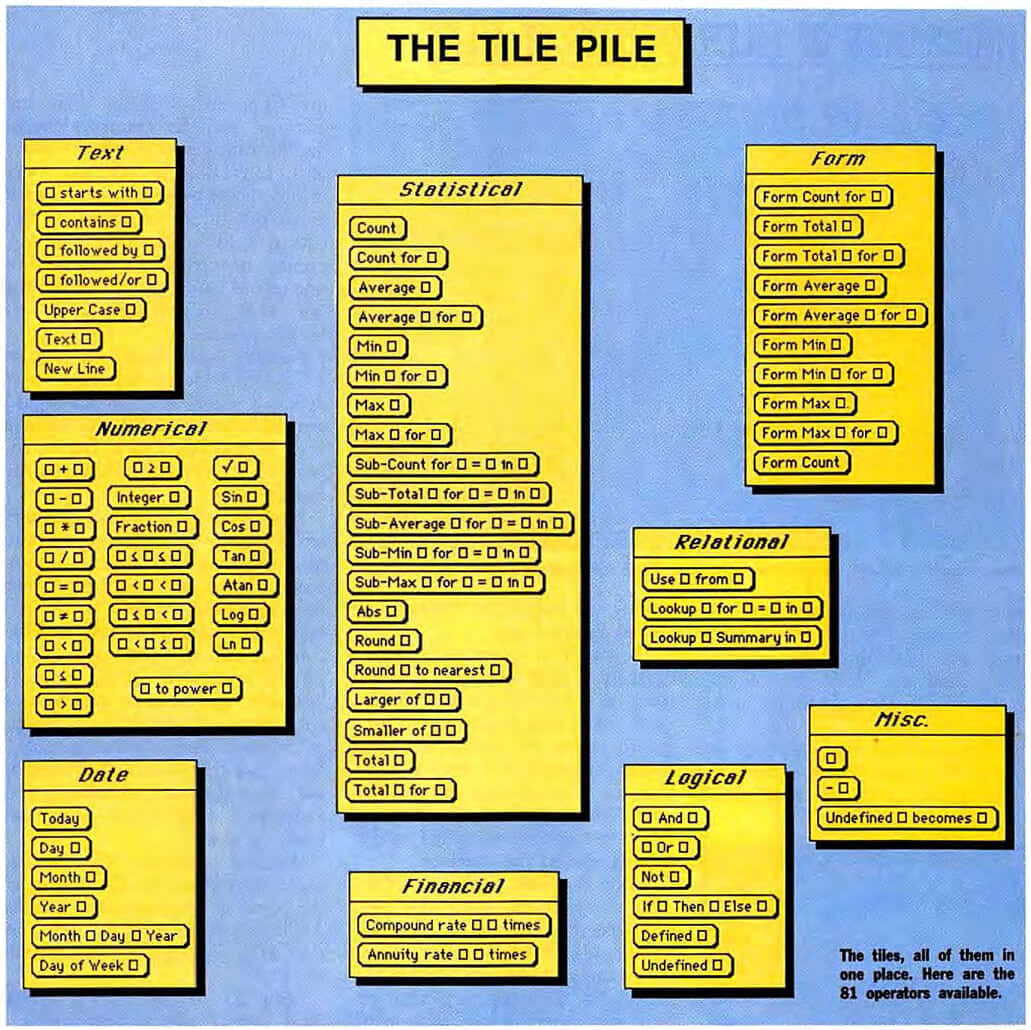

Thousands of Files, Dozens of Tiles

Quite simply, there is nothing comparable to Helix on the Macintosh or, for that matter, on any other microcomputer.

Typically, you can use Helix to build a complex database that can track the sales and monitor the finances of a small to mid-sized company. Helix can provide almost anything that company may need, from analyzing cash flow to managing personnel or controlling inventory.

Odesta describes Helix as an “individualized knowledge base,” and that’s not far from the mark. Helix 2.0 allows you to customize your company or business without having to learn a special programming language to do it.

The Seeds of AppleTalk

High-speed serial ports may have been no substitute for slots (Feb ‘86), but they enabled AppleTalk, a promising technology for the young Macintosh. Alas, in early 1986, AppleTalk was pretty much limited to printing (page 68).

AppleTalk is a local area network (LAN) that can tie up to 32 Macs or peripherals together on a cable up to 1000 feet in length to share resources like the LaserWriter, file and print servers, and other hardware.

Few offices need to push the network to its limits, which is just as well, because while technically capable of serving up to 32 nodes (computers or peripherals), all AppleTalk can realistically handle is between 8 and 10 nodes.

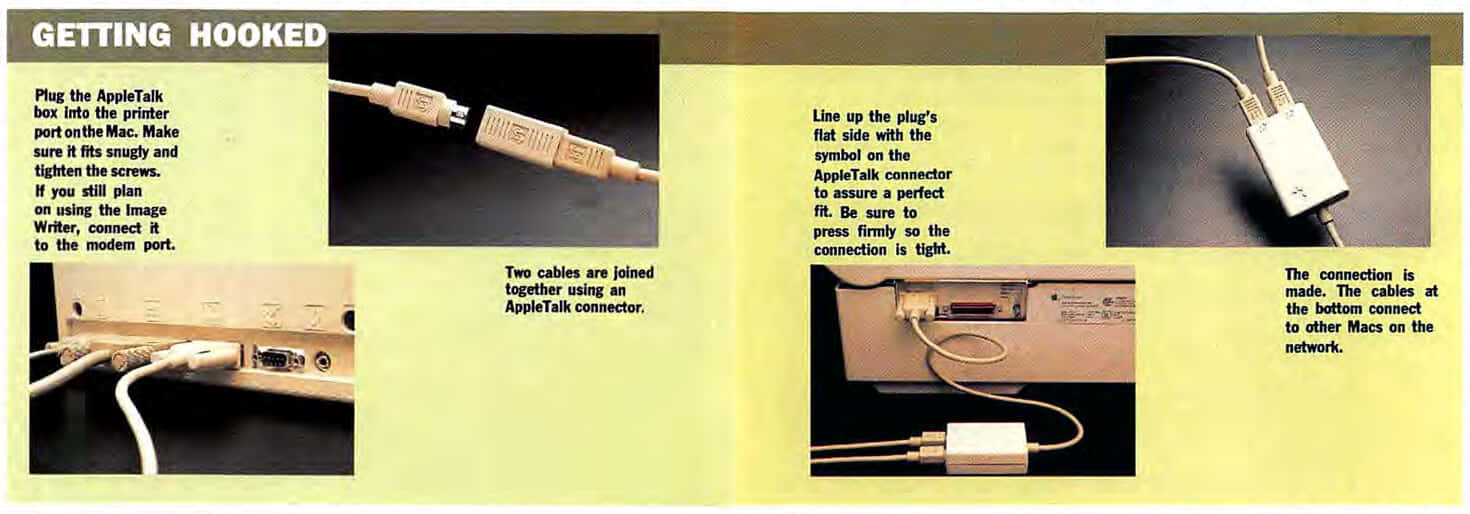

How it Works

An AppleTalk network consists of AppleTalk connectors, AppleTalk cables and cable extenders, each attached to a computer or peripheral via the plug at the end of each AppleTalk connector.

When a device wants to send information to another node in the LAN, it addresses its information according to the other machine’s ID number. Data is sent out through the printer port, where it is fed into the connection box, which functions as a silent “broadcast” system.

Beyond the LaserWriter

So what else can you do with AppleTalk besides print? As of this writing, not a whole heckuva lot. Mac watchers have been straining to see file servers, print spoolers and other high-technology goodies on the horizon, but these predictions have just begun to materialize.

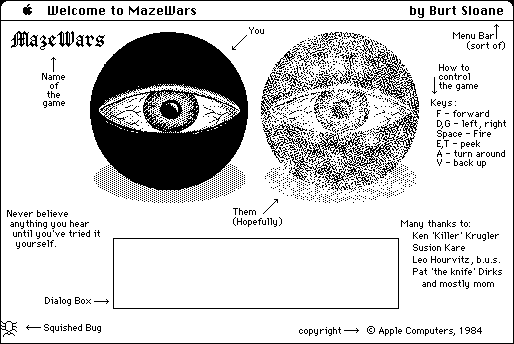

As of press time, about all there is to do with AppleTalk besides share a LaserWriter among terminals is play MazeWars, a multiplayer game in which everyone moves through a maze trying to find everyone else. When you see another player face-to-face (or should we say eye-to-eye, since characters in the game look like gigantic eyeballs with little tails on their backs), shoot first and ask questions later.

We’ll see more of AppleTalk in future issues, including: PhoneNET: Party Line (Dec ‘86).

You can download MazeWars, read Maze War anecdotes and the story of the original Maze War on the Imlac PDS-1 (both from DigiBarn).

MazeWars+ (Nov ‘86) gives you more playing options, including over a modem, but will set you back $50.

Play it Again, Mac!

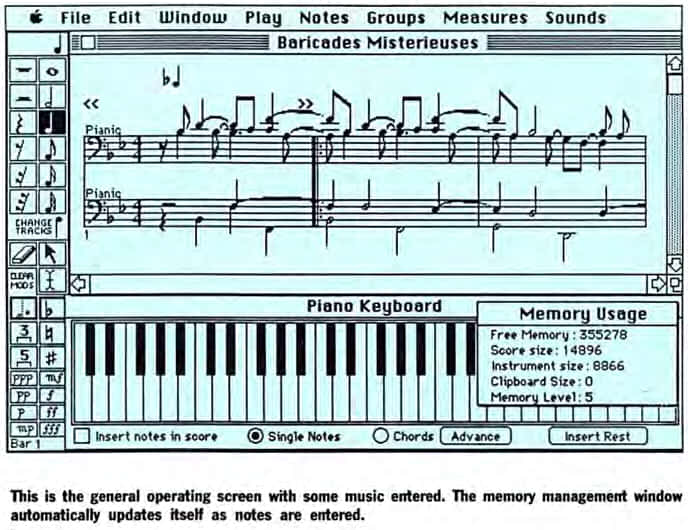

David Barnett brings a whole music studio to your Mac (page 74).

Because the Macintosh has taken the music world by storm. Some of the most interesting and capable programs being crafted for the Mac are designed for writing music. For making exotic sounds.

Deluxe Music Construction Set is a newcomer to the Macintosh music program field, which began with Hayden’s popular MusicWorks and expanded with Great Wave Software’s ConcertWare series.

The main operating screen looks very promising. In the largest window, there’s an empty bar of music staves just begging to be filled in. Bordering it are two other windows that provide most of the ways to enter music into the score. One is the Piano Keyboard, and the other is the Note palette.

Deluxe Music Construction Set hails from Electronic Arts and was also available on the Amiga along with its more famous contemporary, Deluxe Paint. You can download Deluxe Music Construction Set, but it seems to be missing instrument sounds.

I Believe That’s Mate

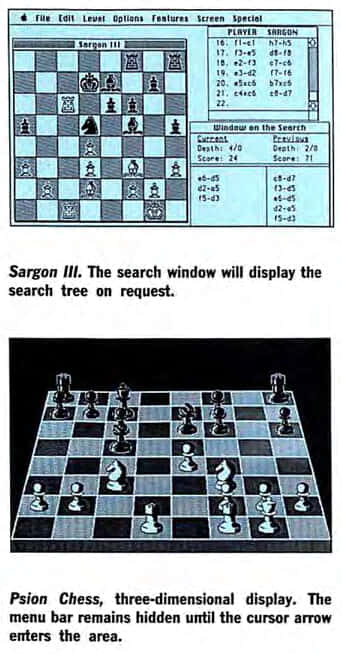

Sargon III faces off against Psion Chess on page 80.

The old master, Sargon III, a classic strategist, took the offensive and maneuvered troops with skill into positions of power. The youthful antagonist, Psion Chess, defended with movements of infinite finesse. As the day closed, soldier after soldier had met with death, and neither commander could find a weakness in the opponent’s position.

Although Psion Chess has an edge over Sargon III in design, both programs offer an excellent game of chess, with enough variations and specialties to inspire long hours of hair-pulling, nail-biting, finger-tapping competition.

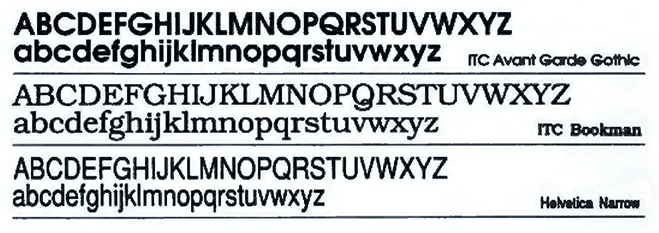

Plus the LaserWriter Plus

Turn to page 98 for a small but significant upgrade to the LaserWriter.

In addition to the Macintosh Plus, Apple announced an enhanced LaserWriter, the LaserWriter Plus, on January 16th. This machine, designed to maintain Apple’s dominant position in the desktop publishing market, has 1 megabyte of ROM, compared to 512K on the standard LaserWriter. The expanded ROM houses seven new font families, for a total of eleven.

MacUser doesn’t mention it, but the new font families are Avant Garde Gothic, Bookman, Helvetica Narrow, New Century Schoolbook, Palatino, Zapf Chancery, and Zapf Dingbats.

The original four LaserWriter fonts are Courier, Helvetica, Symbol, and Times.

For more coverage of the LaserWriter, see Printing the Light Fantastic (Jan ‘86), The LaserWriter Revealed (Feb ‘86), Comet LaserWriter (Apr ‘86). For more fonts for you LaserWriter, check out an Adobe Type Advert (Sep ‘86).

C Programming Series

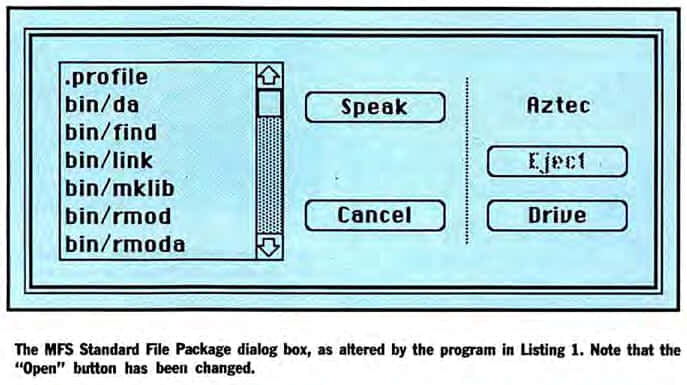

Bob Perez begins a new C series with MacinTalk integration (page 104).

In a recent survey of its Certified Developers, Apple was surprised to learn that these programmers preferred C over Pascal, Apple’s development language of choice and the heart of its Lisa Workshop development system. As a result of these findings, Apple has since included a C compiler in its Lisa Workshop package and has announced plans to produce a native C compiler for the Macintosh itself.

The reasons for C’s popularity among Macintosh developers are many. For one thing, C has become the language of choice for many - if not most - of the developers of software running on other micros.

In this series of articles we’ll present some examples of programming the Macintosh using the C language. We’ll examine many of the Mac’s better known Toolbox calls, of course, but we’ll also look at some of the lesser known routines and show examples of how each can be accessed from C to give your programs a professional, individual look.

This month’s topic is MacinTalk, Apple’s software-only speech synthesizer. There isn’t too much information generally or easily available about MacinTalk, as very little has been done with it by programmers and next to nothing has been written about it. The MacinTalk file itself was shipped to developers in May 1985 and looks like a typical system file, bearing the familiar small-Mac icon. You can obtain MacinTalk from most users’ groups, including some of the on-line groups like CompuServe’s MAUG or Delphi’s ICONtact.

If you’d like to program in C with a 68K Mac, Joshua Stein has a contemporary video series: C Programming on System 6 using THINK C. Applications covered include an IMAP email client, revision control system, and multi-user chat.

Other Features and Reviews

- The Best Laid Plans of Mice and Men - Project Managers (page 54)

- Multiplan, You Look Mahvelous - The original Mac spreadsheet (page 60)

- And In This Corner - Championship Boxing (page 86)

- The Swap Shop - Master the Clipboard, Scrapbook and Note Pad (page 90)

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 86.04 travels to April 1986. We distribute software on paper, get our creative juices flowing, write in Japanese, follow Halley’s Comet, cheat at adventure games, recreate famous battles, and build a calculator.Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏