Mac History 86.09 - SCSI Harder and Faster

This month is the twelfth issue of MacUser US and our twelfth SystemTalk post. Dig into the latest sexy hard drives, the indispensable Fedit Plus, outlining with MORE, and the first surgery sim. Plus another DTP supplement, another terrifying adventure game, and Oscar the Grouch.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the September 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

September 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser September 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

Special System Update

Some relief for System 3.0 users living in fear for their files (page 20).

In early June Apple released yet another version of the System (3.2), Finder (5.3) and related files. Problems with earlier versions had led to two previous releases, but neither fixed all of the original problems.

The story started in January 1986 when Apple released System version 3.0 to go with the Mac Plus. This was the first system software to fully support HFS — and it had serious file-eating bugs. System version 3.0 should not be used by anyone! It will (still) destroy files.

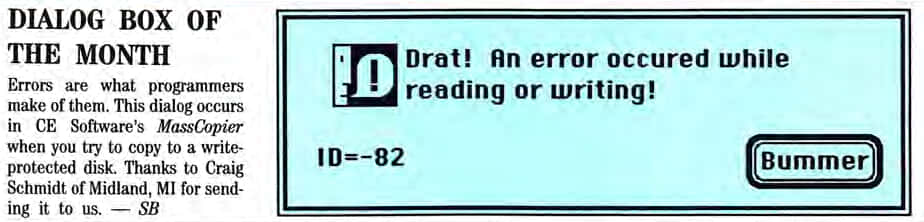

Dialog Box of the Month

Entertaining, if unhelpful dialog boxes were common in the 80s (page 26).

Errors are what programmers make of them. This dialog occurs in CE Software’s MassCopier when you try to copy to a write-protected disk.

Little Companies, Big Compilers

Doug Clapp considers the past and future of Pascal on page 35.

Tom Leonard is a personable young man who, these days, is shipping thousands and thousands of copies of TML Pascal. It’s boffo. It’s a hit. It’s a home run. Tom Leonard will soon go from being merely a bright, personable young man to being a rich, bright, personable young man.

The why’s of all this are interesting. Pascal is the Lingua Franca of Macintosh. More than that, Pascal has been, up to now, Apple’s Language of Choice.

One of Apple’s first employees believed Apple should offer a language better suited to program development. Over the initial objections of Steve Jobs, the employee convinced Apple management to make USCD Pascal an Apple product, after renaming it Apple Pascal, not surprisingly. That employee was Bill Atkinson.

And today we have Macintosh, a machine built upon QuickDraw. And QuickDraw was designed, thought-through, and specified in Pascal. So was MacPaint, a fact that neatly skewers snobs who insist that Pascal is antiquated, clunky, slow and not suitable for developing fast graphic applications.

Why didn’t third-party developers release Pascal compilers capable of creating applications? Because of Apple, which would release its own Pascal development system. Soon. Trust us.

But while Tom Leonard is reaping just rewards, clouds are gathering. Borland International has announced Turbo Pascal for the Mac. As I write this column in early June, Borland hasn’t yet shipped a product, but they might.

Then there’s Apple. And MPW, which stands for “Macintosh Programmer’s Workshop.” And part of it is a real, live Pascal compiler.

For Tom Leonard, there’s good news and bad news in this. The good news is that Apple’s effort sounds baroque and pricey and poor for novices. The bad news is that it may be a powerful, object-oriented, hot-damn affair; the kind of thing that makes programmers swoon.

Soon after, Borland took out big adverts for Turbo Pascal (Nov ‘86).

See also: Seeking the Perfect Pascal (Jun ‘86) and Pascal tutorial (Jul ‘86).

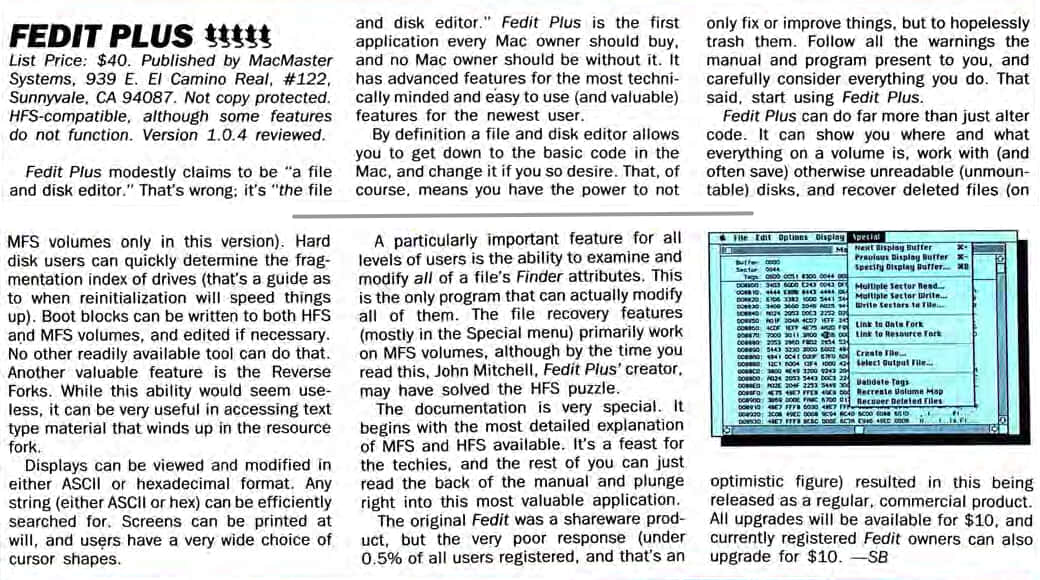

Fedit Plus

On page 40, we find an indispensable utility, but just 0.5% registered when it was shareware.

Fedit Plus modestly claims to be “a file and disk editor.” That’s wrong; it’s “the file and disk editor… Fedit Plus is the first application every Mac owner should buy, and no Mac owner should be without it.

See also: Your First Utilities (Aug ‘86).

More Than Enough

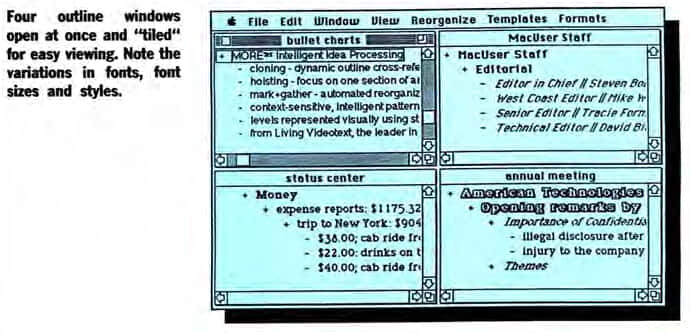

This new outliner, word processor, presentation graphics program is packed full of nifty features (page 44).

It has applications for outlining, of course, but can also be used for desktop publishing and presentation graphics, and it may well be at the forefront of a whole new industry, “Meeting Technology.”

MORE makes outlining very simple, and it contains an incredible richness of features. These include the ability to pick up headlines and move them anywhere in the outline; input graphics, paragraphs, memos or entire letters under a topic; automatically and instantly generate tree charts or bullet charts and incorporate them into an outline or slide show presentation;

Let’s Have Some More

MORE is almost always pleasurable to use, and sometimes tremendously exciting. The power of the tree chart and bullet features is extraordinary. Used to its fullest, this program could single-handedly revolutionize the way meetings are conducted, dramatically speed up time-consuming tasks and result in significant increases in employee and manager productivity.

In the retail trade, every new piece of software is touted as the program that will sell computer systems. It’s a great marketing tool, but nobody pays much attention to it any more because only about two products have ever done it: VisiCalc and Lotus 1-2-3. MORE is a product that could sell MORE Macs (and MORE Mac software) and help Apple make a substantial penetration into the big business market

Find additional MORE coverage in Doing More in Meetings (Jan ‘87).

Harder and Faster

There’s finally a choice of hard disks as SCSI drives hit the marketplace. Head over to page 52 to see six of the latest offerings.

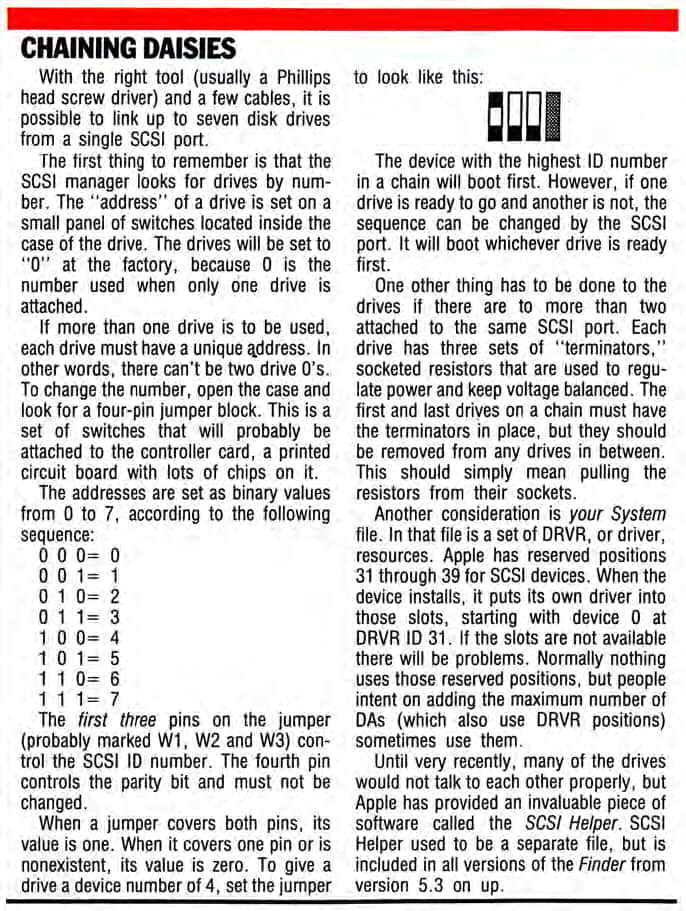

SCSI (pronounced “scuzzy” or, in the Mac community, “sexy”) stands for Small Computer Systems Interface. A SCSI connector port is built into the Mac Plus and can be added to a 512K Mac with the installation of a peripheral card or Mac Plus upgrade. The required control software (the SCSI Manager) is contained in the 128K ROMs. The SCSI port conforms to a set of industry standards. Though mechanically similar to other hard disks, SCSI drives connect to the Mac Plus through this special high-speed port.

Checking out the SCSI

I have had a total of just over 200 megabytes sitting next to my Mac for several weeks now. The drives fall into three basic types: internal SCSI (the MicahDrive AT), affordable external (SuperMac, Peripheral Land, Peak Systems and LoDOWN), and mongo external. The mango drive is the AST-4000, a 74-megabyte drive with 60-meg streaming tape backup. At just under $7000 it’s in a category by itself and will be considered separately (see box).

SCSI in the Suburbs

Once you’ve driven a SCSI hard disk, you’ll be spoiled permanently. About the only other way to seriously increase speed on the Mac Plus is with tons of RAM. Put the two together and your Mac can be the first computer to reach hyperspace by itself.

See also: A Hard Mac is Hard to Find (Feb ‘86) and The Joy of Hard Driving (Jul ‘86).

Desktop Publishing Supplement

I’ve chosen two pieces from this month’s DTP supplement, starting with professional charting on supplement page 4.

The pieces we don’t cover are Power Word Processing (page 12), Desktop Publishing Tip Sheet (page 17), Hot off the Presses: MacPublisher II (page 22), and Desktop Publishing Directory (page 30).

The first DTP Supplement was published in June ‘86.

Chart Your Way to the Top

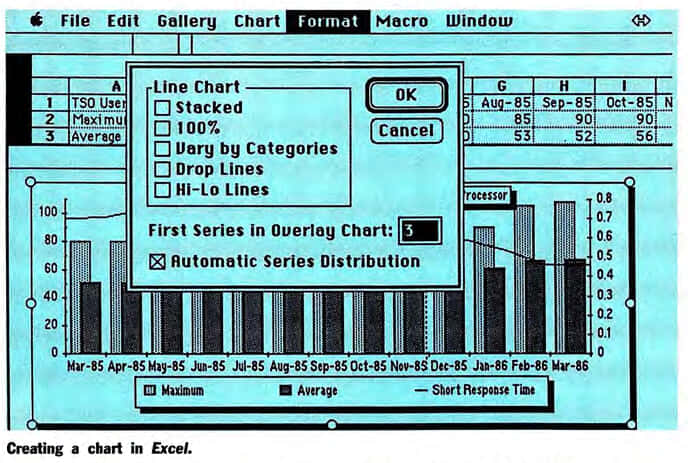

If there’s one thing management likes even more than word “productivity,” it’s business graphics. Charts and graphcs allow busy executives to figure out how their company or department is doing at a glance, without having to add up figures, or even be able to read.

The trick to successful charting with Excel is learning how the menus work. In general, the menu items work on whatever is selected at the time. Click on the Value axis (the vertical one) and the Format menu works on that axis. You can change the font, move or eliminate the tick marks, or change the scale. Click on the legend (after adding one from the Chart menu) and the fonts used and position of the legend can be altered using the Format menu. Choose SELECT CHART from the Chart menu and you can globally change fonts and sizes, or add a border shadow.

We’ve plenty of other Excel coverage, including MacUser’s review of Excel (Oct ‘85) and a guide to creating Excel macros (Dec ‘85).

The Linotronic Connection

On DTP supplement page 20, we learn how to connect your Mac to the world of professional typesetting.

The LaserWriter is a tease. Publishing professionals may love it, but they still need more quality than it can deliver. Camera-ready text and graphics for commercial-quality printing require higher resolution than the LaserWriter’s 300 dots per inch.

One professional-level solution is the new line of typesetters from Allied Linotype, the Linotronic 100 and 300. These are full-featured typesetting machines, and along with the LaserWriter, use Adobe’s PostScript page description language, making linking them to a Macintosh-based desktop publishing system easy.

Operating the Linotronic is fairly straightforward. The output paper is loaded into its holder in a darkroom, or it can be purchased pre-loaded from the paper supplier. (Be prepared to dedicate a room in your facility for loading paper. The paper is photographic, meaning that it should be kept away from light. The room should also contain a sink with running water.)

Linotronic printers are certainly the Rolls Royces of the desktop publishing world. If your publishing needs require commercial quality output, these machines have the power to provide it, without separating you from the Mac and your favorite software.

In 1986, a Linotronic 100, with a resolution of 1270 lines per inch would set you back $28,950 including RIP. The Linotronic 300, with a maximum resolution of 2540 lines per inch went for $49,950 (equivalent to $102,000 in 20201).

You might enjoy this Linotype Presentation from Drupa 1990:

Adobe Advert

At the back of the DTP supplement, we find this advert for Adobe System Type Library. Look at that Adobe logo!

Sometimes it takes the drama of Benguiat to get the message across. Or the immediacy of American Typewriter. Or the authority of Bookman Bold.

See also Plus the LaserWriter Plus (Mar ‘86) and World-Class Fonts (Oct ‘86).

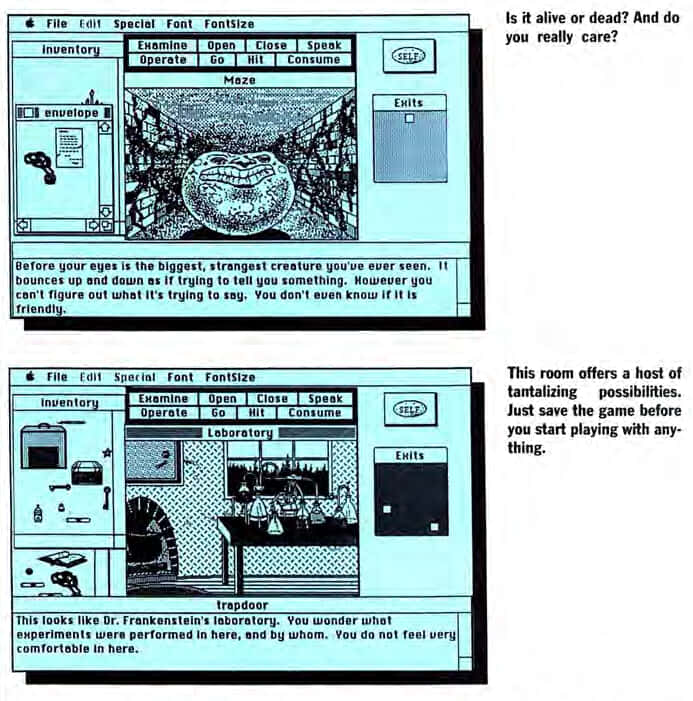

You are Cordially Uninvited

Explore a haunted mansion in Uninvited (page 103).

Welcome to the haunted mansion. Sorry about that little accident in the road, the one that stranded you on the doorstep of this uninhabited mansion as a storm rolls in. The good news is, you’re just in time for lunch. The bad news is, you could be it — but then, you were cordially Uninvited.

This icon-based adventure was designed by Icom Simulations, the same highly talented group responsible for the groundbreaking Deja Vu: A Nightmare Comes True. Uninvited takes the Deja Vu game style one step further, though, by using limited animation sequences and digitized sound effects to add color and depth to the game. But if you think this game will be any easier than Deja Vu, you’re dead wrong. And probably just plain dead as well.

Each puzzle may seem maddeningly impossible at first, but give yourself a chance to mull over problems before you get too frustrated. There is a simple, usually very logical solution to each mystery. In fact, each step in the puzzle is so logical that we found ourselves wondering how we couldn’t have figured it out immediately — after we had spent two days pondering it, of course.

With Uninvited, Icom Simulations has once again asserted itself as the Mac’s foremost adventure game design team. These guys (yes, they’re all male) can do things with adventure games that you’ve barely even dreamed of. The only bad thing about Uninvited is that, once you’ve solved it, you’ve solved it, and you have to wait until the next release for new adventuring thrills.

Modern critics have been less kind to Uninvited, with The Digital Antiquarian going so far as to use it to illustrate The 14 Deadly Sins of Graphic-Adventure Design (filfre.net).

For ICOM’s first adventure, see Deja Vu: A Nightmare Comes True (Jan ‘86).

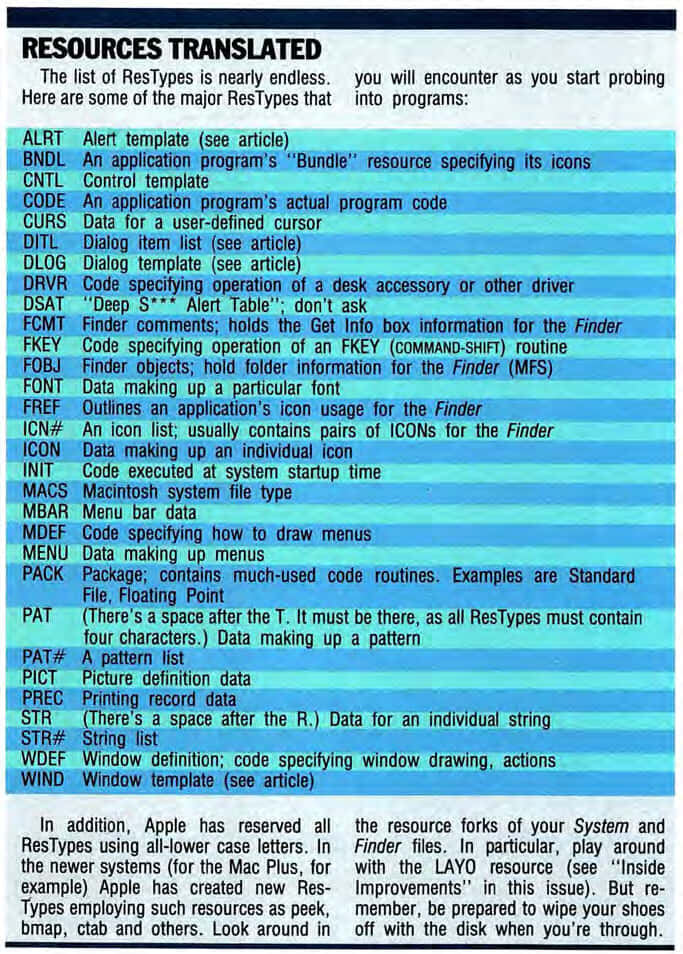

Tapping Mac’s Natural Resources

Uncovering the resources (and monsters) inside Mac applications on page 108.

Oscar at the MontClair Film Festival by Neil Grabowsky under CC BY 2.0

Oscar at the MontClair Film Festival by Neil Grabowsky under CC BY 2.0

And there, down in the corner, is that familiar little trashcan that houses a smiling Oscar the Grouch. Huh? Wait a minute.

“That trashcan. Where’d it come from? What happened to your Mac’s trashcan?”

“It’s no big deal, I just altered it a little with Resource Editor.”

“You mean, you altered the Finder?” you ask, incredulously.

“Sure. It’s not hard.” The salesperson carefully disguises the fact that this is the first time in 3 years that he’s known something that a customer didn’t. He smiles smugly.

“You changed the Finder’s code? How did you know how to change the Finder? How did you know where to look in the program? How did you get so smart, anyway?”

“I didn’t have to change the code,” he replies. “I just altered the trashcan icon in the resource file. You do know about resources, don’t you?”

Check the rest of this article for theoretical and practical advice on resources.

ResEdit is also put to use in Dressing Your Mac For Success (Feb ‘87).

Letters

On page 137, Paul Wilfong wants to bring Lisa 7/7 to the Macintosh.

There are a few points I’d like to make. (1) Many Macintosh systems now typically consist of a megabyte of memory and a 10- to 20-megabyte hard disk. (2) The Mac should have multitasking. (3) Lisa 7/7 is a true multitasking environment designed to run on a machine with 1 megabyte of memory and at least a 5-meg hard disk. The conclusion is obvious: Use Lisa 7/7 to get multitasking on the Mac!

Apple’s Dan Cochran replies:

Paul…I don’t think I’m gonna win any points with my answer, but your question is a good one and deserves attention. I’ll certainly concede to your first three points. There are really three reasons, two technical and one semi-political, why a Macintosh 7/7 port is infeasible.

First, an application (eg., 7/7) does not necessarily nor usually implement multitasking in the true sense. A true multitasking environment must begin at the operating system level…

…The real solution lies in your second statement, “The Mac should have multitasking.” Maybe someday it will.

I’m trying to find a good picture of Lisa 7/7 to include.

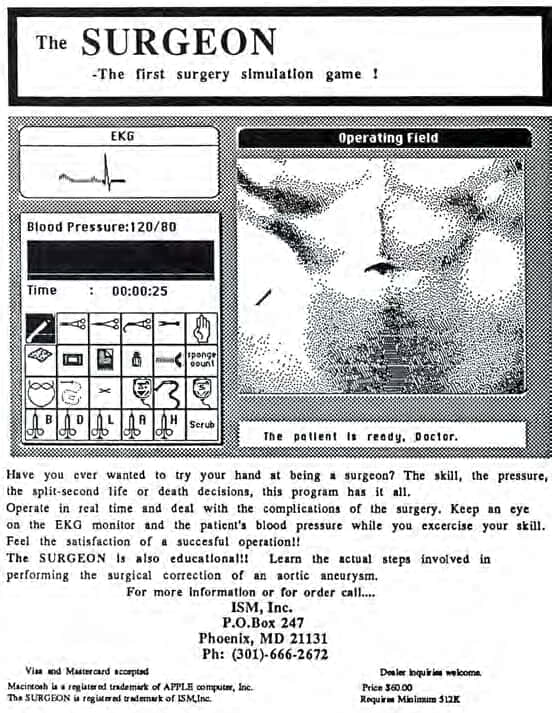

The Surgeon Game

Have you ever wanted to try your hand at being a surgeon? Check out page 152.

Other Features and Reviews

- The Graphics Gallery: PictureBase organises images (page 60)

- Inside Improvements: modifying applications (page 120)

See also DTP Supplement.

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 86.10 travels to October 1986. The editor is missing his mouse, we check our spelling and change our desktop pattern, read reviews of Microsoft Works, FullPaint, and Archon before attempting to defuse a few bombs, or at least identify them. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏