Mac History 86.10 - FullPaint and Archon

This month, the editor is missing his mouse, we check our spelling and change our desktop pattern, read reviews of Microsoft Works, FullPaint, and Archon before attempting to defuse a few bombs, or at least identify them.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the October 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

October 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser October 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

MacVision Advert

We begin this month with live action on page 8:

Musings on a Flat Mac

Neil Shapiro is missing his mouse on page 9.

So I figured a CP/M laptop with WordStar would solve my problem. I knew that I would miss my Macintosh, but I didn’t think that withdrawal would be this terrible.

Once in a while, though, you do hear about a laptop portable Mac. But that one never seems to be rumored at anywhere near the same completeness as the other Macs. That’s not very surprising when you consider that all of the other kinds of Macs simply play off on the features and engineering of present Macs. But a laptop Mac (often called a Flat Mac) would certainly have to feature a number of new steps forward.

Even the most basic design principle would have to change - you would not want a mouse on a laptop machine. A trackball, perhaps, or some sort of thumb-operated wheel might do it. An LCD screen is slow and hard to see (take my word for it) and so we might have to go to something like a plasma or electroluminescent display.

We need a Flat Mac (I happen to need one in the next 10 minutes, unfortunately). When will it happen? Soon, I hope. I wouldn’t want to see Apple miss an opportunity that seems to be so great.

Macintosh Portable photo by Rama under CC BY-SA 2.0 FR

Macintosh Portable photo by Rama under CC BY-SA 2.0 FR

Third parties (such as Dynamac) made luggable Macs as early as 1987; see Give Me A Lite — A Mac Lite (Feb ‘87). Apple’s first luggable Macintosh appeared in late 1989 in the guise of the 7 kg (16 lb) Macintosh Portable.

However, a lightweight, portable Macintosh had to await the PowerBook 100 series in late 1991, five years after Neil wrote this. The PowerBook was great, but it was a long time coming.

Neil doesn’t mention which CP/M laptop he has, but an interesting example is 1984’s Epson PX-8 Geneva (oldcomputers.net).

What’s the Disk Worth

How much did software cost to make in 1985? Disks, box, manual, labels… and programmers need to eat. Page 31 has the answer:

Here’s what it costs to make a piece of software: $10.40.

That’s it: $10.40. What you can charge for that piece is up to you. $39.95? $55? $74.95? Up to you. Charge more and you’ll make more, if you sell the same amount as you would with a lower price. But it doesn’t work that way, usually.

Only one cost left, and it’s a killer: royalties.

For books, it goes like this: authors usually get from 10 to 15 percent of the “net” that the publisher receives. If a book costs $20, publishers may net about $10. The author gets a buck. If he or she is a name author, or if the book has already sold a zillion copies, it may be $1.50.

Many software publishers pay programmers the same way, and net about the same percentage. But software usually costs more than books, so programers, the theory, make more a unit. At a retail price of $55, software publishers may net $25 to $30. The programmer may get $2.50 to $3.

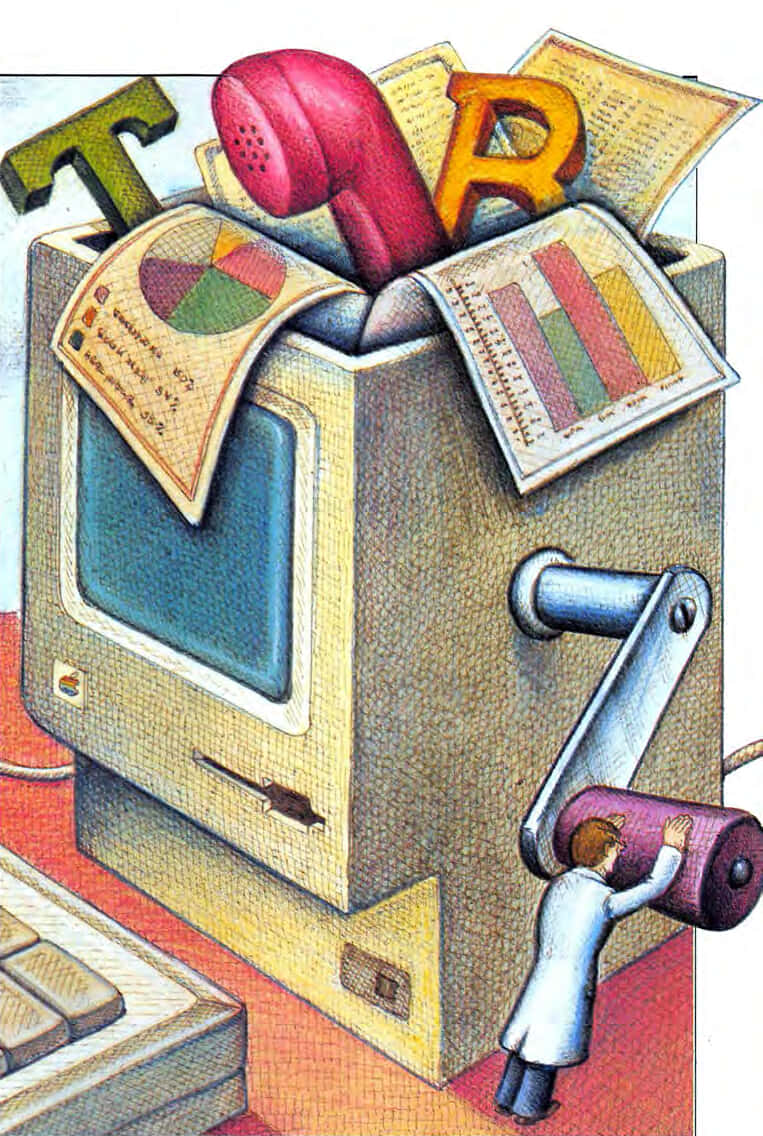

It’s in the Works

Microsoft Works offers an integrated package for $295 (page 42):

You certainly have to hand it to the people at Microsoft; they understand the Macintosh interface and how to design programs for the Mac as well as any company in the world and better than many. The new Microsoft Works program is an integrated and yet introductory package that will have you mousing its word processor, spreadsheet and charting, data base and telecommunications subprograms in a very short time.

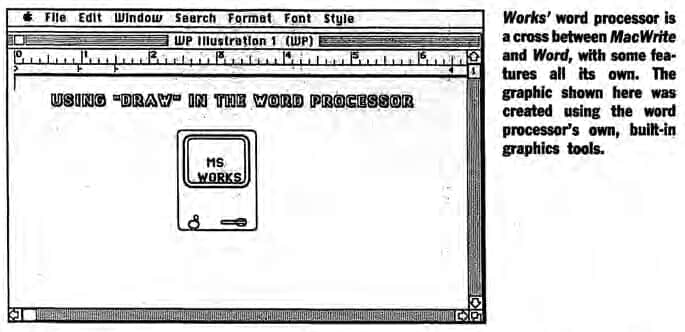

The Word is Not “Word”

Take Microsoft Word, throw in an equal helping of MacWrite and a tiny dollop of MacPaint and skim off all the fat and there you have it, the recipe for the word processor section in MS Works. All the usual text-editing commands work as most Mac owners have come to expect. Double-click on a word to highlight and select it for cutting or copying; drag the mouse cursor through a range of text to select that. Position an insertion point cursor (using the mouse) any place on the page, while you can scroll the text window by dragging the mouse off the top or bottom of the screen. All in all, the word processor in MS Works is more capable than MacWrite 4.5 and, in some respects, easier and more enjoyable to use than Word.

Spreading It On

Let’s get this said right away the spreadsheet in MS Works is not going to keep Excel buffs up all night. Neither will it seriously threaten the positioning of Multiplan. What you get in the spreadsheet and charting subprogram is a very workmanlike spreadsheet that follows the Macintosh interface, coupled to some modest abilities to chart the figures sheeted.

A Lust for Lists

The data base in MS Works is truly intuitive and a pleasure to use. Of course, it does not have many features of more complex data bases such as hierarchical file structures, graphics support and the like. But, again, for the target audience it hits a bullseye.

The Terminal End

Telecommunications has become a way of life — and business — for tens of thousands of Macintosh owners. MS Works also allows the user to utilize his or her modem to access on-line services, networks, BBS systems and other Macs and computers.

The telecommunications subprogram in MS Works is good enough that it will take the user through the first stages of being involved with modems and the exchange of data via the phone lines. Many users may find that it is all that they will need. But unlike the other subprograms in MS Works, the lack of the above features makes this part of MS Works compare as being less than existing standalone products.

All Together Now

MS Works, price point is another of its strong points. In order to come up with a comparable batch of programs running under Switcher it would be necessary to dip deep into a wallet. For many people the most economical way to integration of all of these programs might well prove to be MS Works. This may indeed prove to be the package that changes the way you use your Mac! It’s well worth auditioning it to see if it will really work for you.

Check it Out

In 1986, your word processor didn’t include a spellchecker. Nine spelling checkers reveal their innermost secrets on page 68:

You say you don’t spell real well? Or your fingers don’t type exactly what your brain wants them to? And dictionaries are big, heavy and slow to use. Anyway, how do you find the word if you don’t know how to spell it? The answer is a spelling checker program, a piece of software that will solve all your spelling problems. Or should. Our reviews reveal that some come close, some do specialized checking better than others, and some just don’t make it.

Recommendations

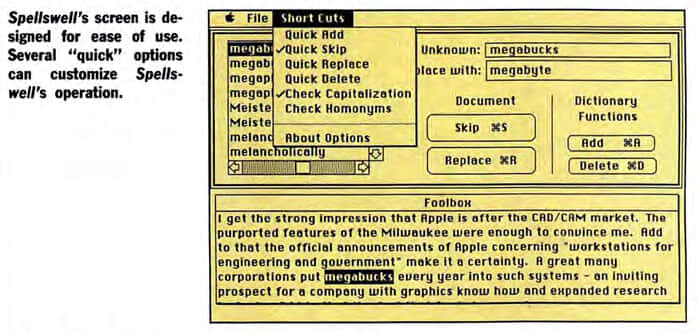

None of the programs we reviewed possessed all the qualities we would like to see. Our highest recommendation goes to Spellswell. Spellswell works with both Word and MacWrite; is not limited to a certain number of unique words, and the price is reasonable. Overall, it is a pretty good value.

Spellchecking is a surprisingly hard problem. Dr Roger Mitton wrote Spellchecking by Computer for The Spelling Society (1996). In 2020, one programmer attempted to rebuild the world’s most popular spellchecker, it didn’t go well.

My Paint Runneth Over

We got a quick review of FullPaint in June ‘86, now we go in-depth on page 78:

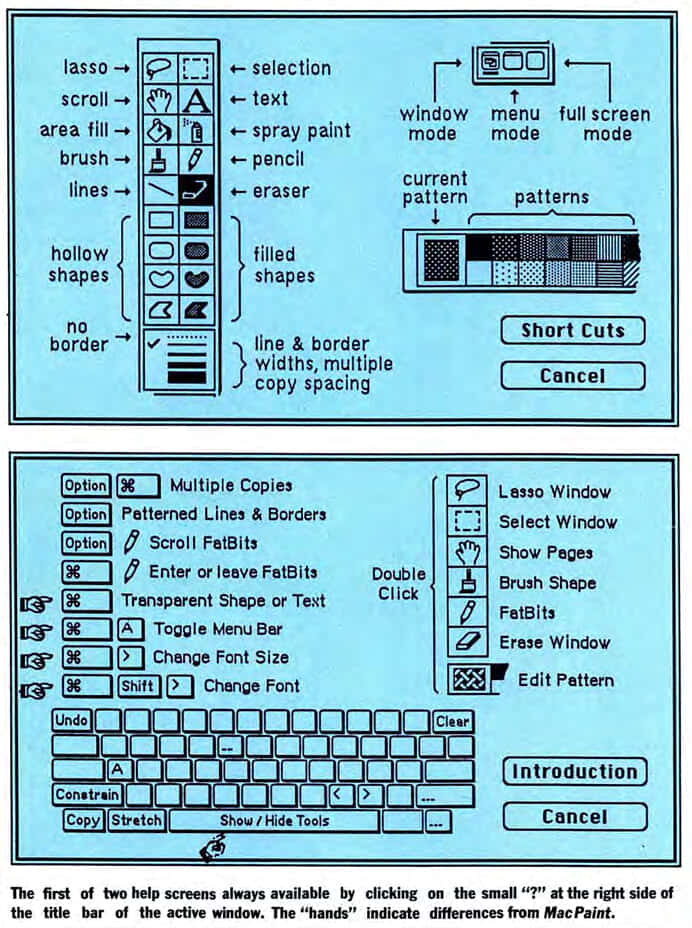

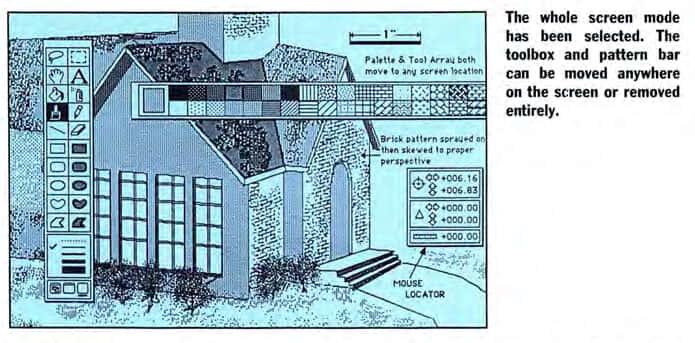

Since the Mac came out, developers have tried to build a better MacPaint by designing desk accessories and add-on “support” programs. Now Ann Arbor Softworks has gone a step further — created a better Macintosh paint program—and has done it well. FullPaint takes MacPaint and extends it in every direction.

The full screen gives you a good 80 percent more work area than the MacPaint screen we’ve come to know and (sometimes) hate. In the full screen mode you have the complete Mac screen area to work in.

All in all, though, the more you use MacPaint the more you’ll appreciate FullPaint. Except for the abominable copy protection—which cost the program a full mouse in overall rating—its few quirks are easily overshadowed by its added functions and added depth.

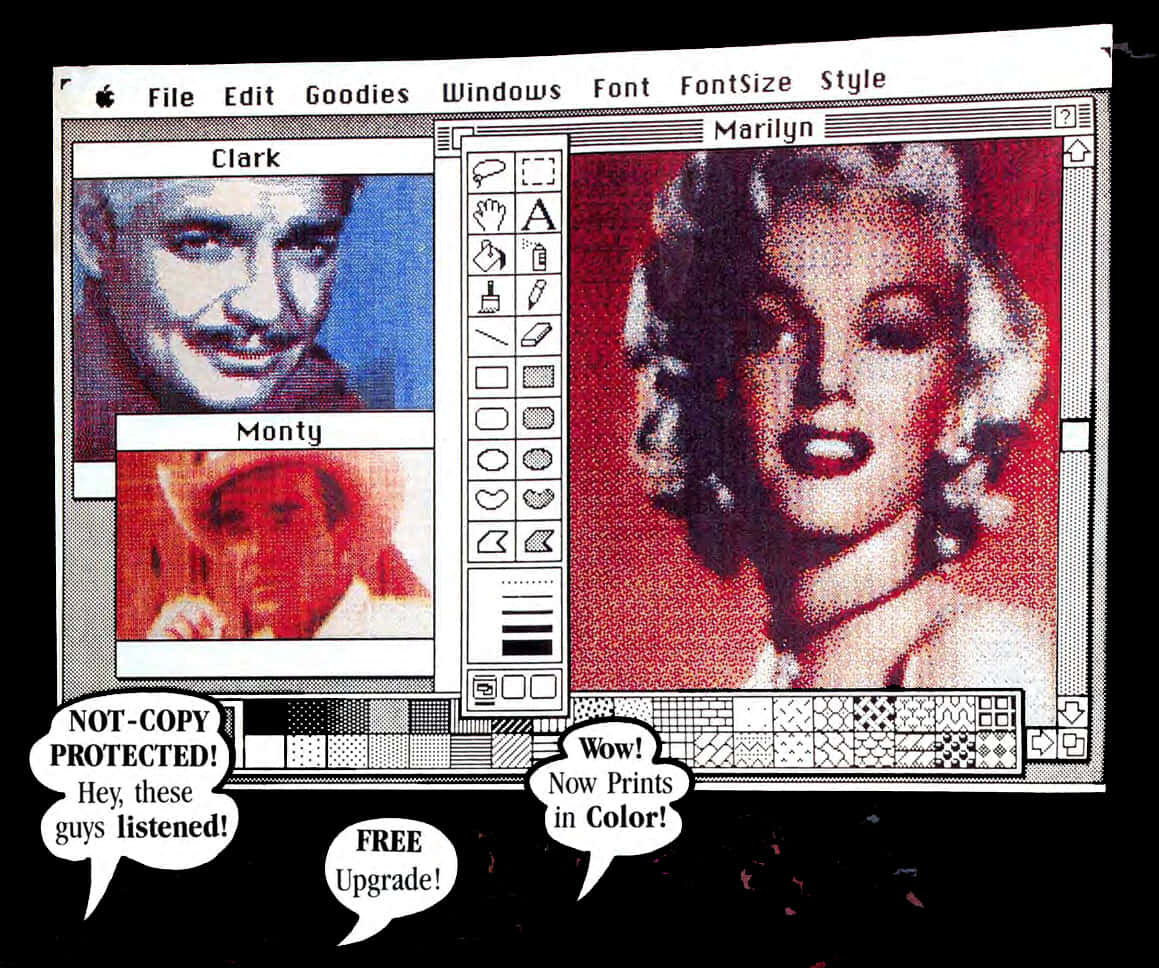

There’s a double-page advert for FullPaint on pages 6 and 7 that touts its colour printing capabilities and the removal of the “abominable copy protection” that so frustrated the reviewer:

32by32.com has a feature on FullPaint: it only enjoyed a brief time in the limelight, never making the transition to on-screen colour. Early in 1987, It’s Draw, It’s Paint, It’s SuperPaint! (Feb ‘87) raised the bar for paint packages.

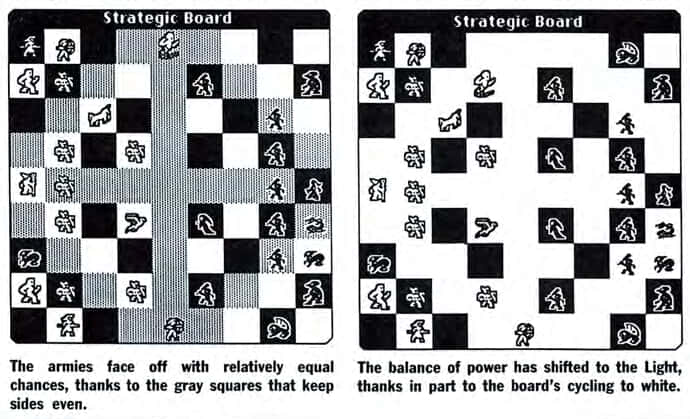

Archon

Tracie Forman Hines checks out the Macintosh port of Archon (page 92):

Have you ever seen a live-action chess game, where people actually playing the roles of the pieces move around in a huge board? Computer game designer John Freeman has. He’s even participated in them himself. The was what first gave him the idea behind Archon.

This strategic challenge of wits combines elements from chess and Capture the Flag, with a dash of medieval mythos thrown in for good measure.

Each army is different, but equal. For example, the light Knights and the dark Goblins both function in much the same ways that chess pawns do…

Having been designed in shades of black, white and gray, Archon is a graphic natural for the Mac — or at least, it should have been. Unfortunatly, the game’s graphics weren’t redesigned to look any sharper than they did on the old 48K Atari or the Commodore 64.

Archon may not shine as an action game, but its strategic challenge will keep players flexing their mental muscles for some time to come.

The Digital Antiquarian has an excellent article on Archon:

This very likely marks the first example of adaptive AI in the commercial game industry, a radical step in the direction of friendlier, more accessible gameplay — and in the direction of Trip Hawkins’s vision of consumer software — that deserves to be celebrated more than it has been.

Archon is only playable from a floppy on a Mac 512K or Mac Plus. However, you can run a cracked version using Mini vMac. The Macintosh Garden entry: Archon: The Light and the Dark has the download.

Or watch an Archon Let’s Play on a real Mac Plus:

1Bit Fever Dreams explains Mac Plus video capture in the video description:

The video signal comes straight from 4 wires from inside the Macintosh Plus, into a RGB2HDMI device that I self-assembled by using the info in this project: https://github.com/hoglet67/RGBtoHDMI

MacGolf Advert

Practical Computer Applications are touting a golf game on page 94:

MacGolf challenges beginners and experts with 3-dimensional animated golfers and graphics, realistic (digitized) sound effects, and two 18 hole golf courses. Up to four people can play.

MacGolf is briefly covered in Games to Shoot or Boot (Jul ‘86).

Finder’s Keepers

The Finder is the centre of attention in the feature on page 110:

Do you remember when you first got your Mac, looked inside the System folder, and found a few little Macs - one labeled System, and one labeled Finder? The System was easy enough to accept, even if you weren’t entirely sure what it was every computer needs some sort of operating system. But the Finder… what in the world was that for?

The desktop is so much a part of Mac that it seems hard-wired, somehow already hiding behind that gray screen when you turn the Mac on. But, it’s only the Finder doing its job. The Finder itself is “just” another application; and, like other applications, it can be upgraded - and it has been, a number of times.

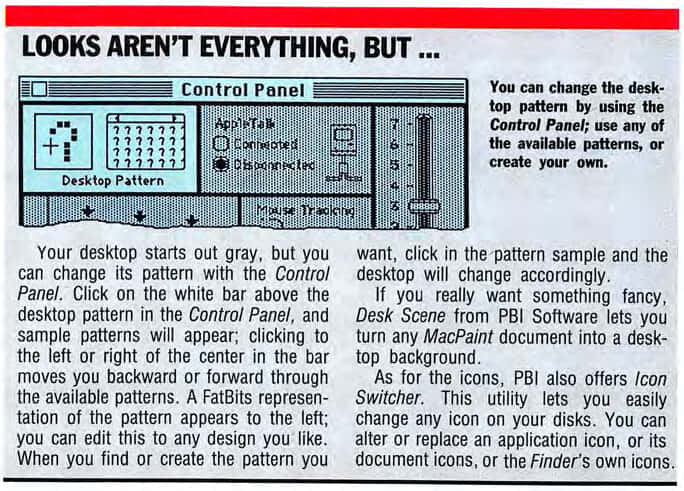

Your desktop starts out gray, but you can change its pattern with the Control Panel. Click on the white bar above the desktop pattern in the Control Panel, and sample patterns will appear; clicking to the left or right of the center in the bar moves you backward or forward through the available patterns. A FatBits representation of the pattern appears to the left; you can edit this to any design you like.

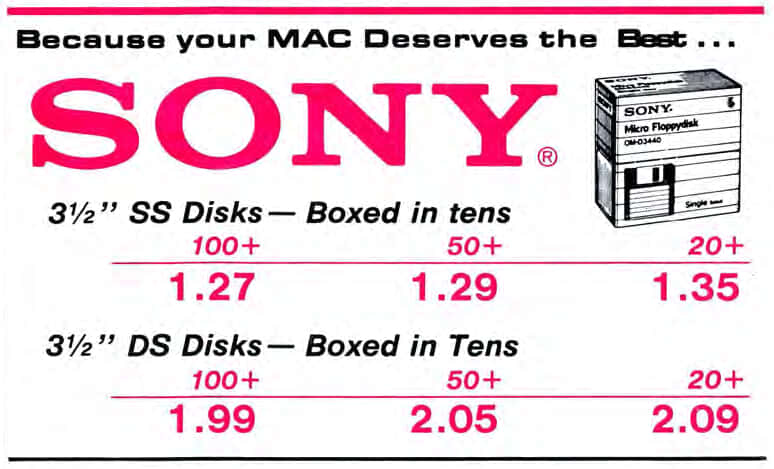

Floppy Disk Advert

Best Computer Supplies sells floppies in bulk on page 117:

Tip Sheet

On page 120, readers write in with their tips.

To temporarily disable the internal speaker, type ATM0 from your terminal program and RETURN. An “OK” verifies that the volume control is set to off. To turn it back on, type, ATM1 and press RETURN.

Bombs Away

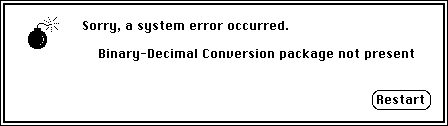

If you were an early Macintosh user, you caught your fair share of bombs. On page 125, reader Augustus Schoen-Rene seeks answers from the Mac Team:

I am sure that most every Mac user has run into a bomb at least once and not understood what was going wrong. For instance, I am running into a lot of numbers 14 and 10. What are these? What do all the other numbers mean?

I suspect Augustus would have been disappointed with the answer:

No document can detail the various Macintosh system errors because system error codes themselves are not very descriptive. The Macintosh provides almost no internal error reporting mechanism and the architecture’s complexity usually renders the error codes meaningless.

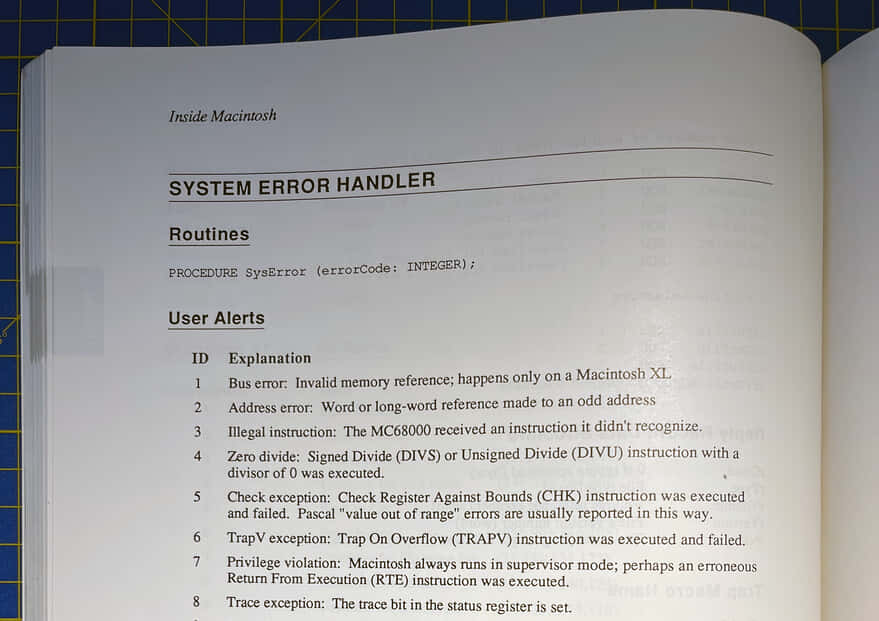

The reply goes on to provide terse descriptions of some error codes. Thankfully, we can seek enlightenment on page 176 of Inside Macintosh Volume III:

Not feeling enlightened? Maybe Apple Technical Comms were right after all.

Download a PDF of Inside Macintosh Volume III courtesy of Vintage Apple.

See also: Software Isn’t Fragile (Oct ‘85).

Other Features and Reviews

- As the Helix Twists: Double Helix reviewed (page 52)

- What’s Hot, What’s Not with Doug Clapp (page 60)

- Thoroughly Modern MAUG: the biggest online user group (page 86)

- A Play on Words: Macintosh word games (page 98)

- Pascal Programming Series, Part 3 (page 104) - started Jul ‘86

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 86.11 travels to November 1986. We gaze at the Radius Full Page Display, hear of the fabulous Motorola 68040, create a blockbuster storyboard, return to labyrinthine wars, and dust off the mahjong tiles in Shanghai. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏