Mac History 86.11 - Radius Full Page Display

This month we gaze at the Radius Full Page Display, hear of the fabulous 100 MHz Motorola 68040, create a blockbuster storyboard, return to labyrinthine wars, and dust off the mahjong tiles in Shanghai.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the November 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

November 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser November 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

Turbo Pascal Advert

Inside the front cover, we find an advert for Borland Turbo Pascal.

Doug Clapp discussed TML Pascal and the competition from Apple and Borland in Little Companies, Big Compilers (Sep ‘86).

Apple Programmer’s & Developer’s Association

On page 6, you’re invited to join the APDA.

The creator of the Pinball Construction Set (Jul ‘86) is a member, so what are you waiting for?

The Reek of Hot Toner

This month’s editorial sees Neil Shapiro talking desktop publishing with printers (the people, not the hardware) on page 15.

Printers can be very conservative. I’m entitled to say that because I have a bachelor’s degree in printing (along with journalism and photography) from the venerable Rochester Institute of Technology.

Only one thing can stop or slow down the desktop publishing revolution - and that is today’s printers and the printing industry. I am stopping short of predicting a secret cabal of printers wearing black armbands with silhouettes of Linotypes on them actually coming to your home or office, swinging lead-alloy sledgehammers and trashing your LaserWriter. But that’s just because I don’t think they could get away with that.

It’s Easier than Ever to Get Together

Apple’s commitment to User Groups is more than mere hype on page 33.

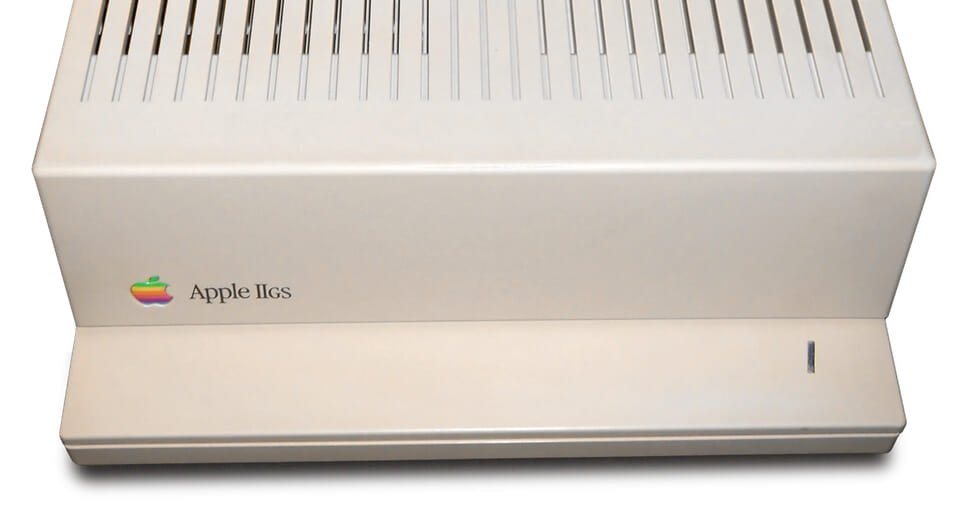

Enter the IIGS

Michael D. Wesley asks how the IIGS fit into Apple’s product line and speculates on a future Motorola CPU (pages 35 and 38).

Jim gets a bit confused at this point and asks the dealer to explain the difference between the IIGS and the Macintosh. The dealer says that the IIGS is a “high-end consumer” machine, while the Macintosh Enhanced 512 is a “low-end business product.” After a short demo of FullPaint on the Mac, Jim is quickly maneuvered over to the Mac Plus, the current “high-end” business tool. (“Until,” the dealer says secretively, “the open Mac comes out.”)

Apple IIGS photo by Cbmeeks in the Public Domain

Apple IIGS photo by Cbmeeks in the Public Domain

What Apple has with the IIGS is a fast and powerful color machine, with some of the capabilities of Macintosh. It uses a central processing chip that makes it possible to expand the machine’s memory up to 8 megabytes. It runs existing Apple II software up to 2.5 times faster than a IIe. The IIGS has window, menu and font managers and a complete “toolbox” so developers of new products can access QuickDraw. The IIGS is the first computer to reflect Apple’s commitment to bring the Apple II and Macintosh lines closer together. And it has color and sound that have to be experienced to be believed.

We have full coverage of the IIGS next month in A Mac of Another Color (Dec ‘86).

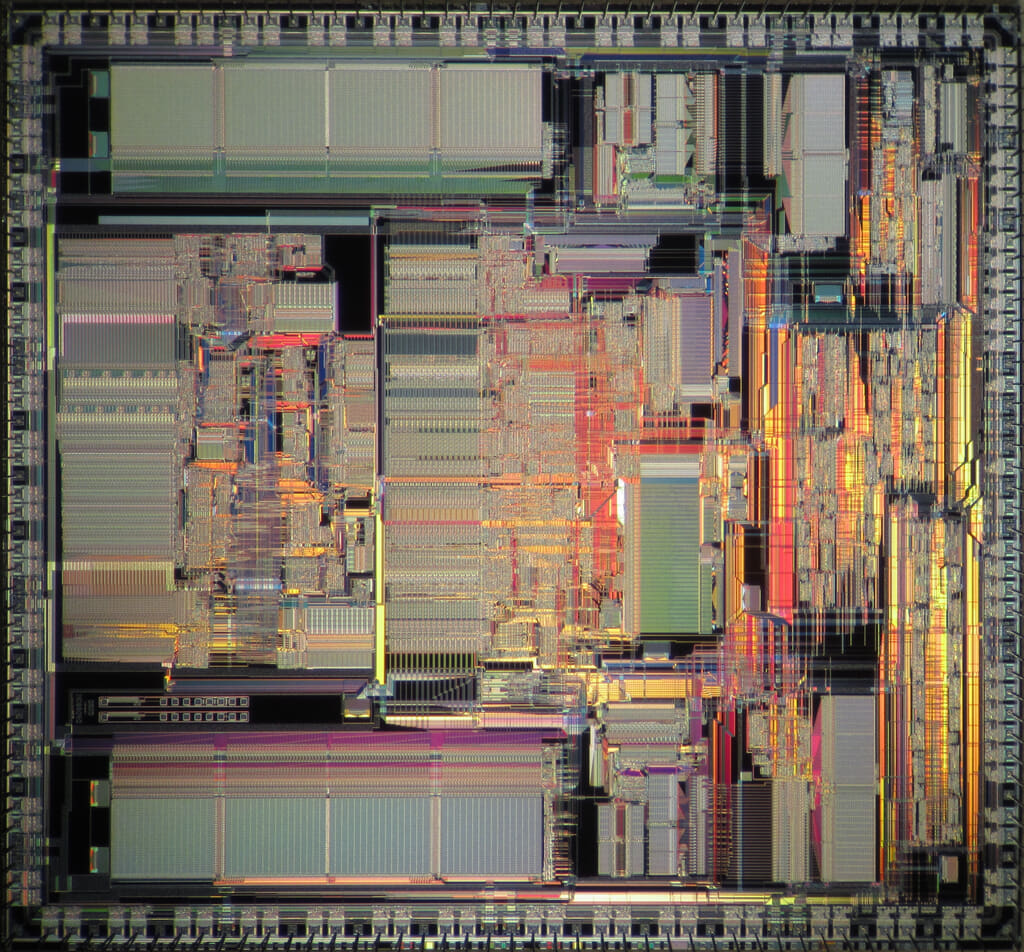

More of the Future

Beyond the 68000 lies a region as yet unexplored but with almost staggering potential. The next generation — the 68040. The Mac’s 68000 is a 16/32-bit processor and the 68020 is 32/32 (or “true 32-bit”) cruncher. Well, according to rumor, the 68040 is designed to be a 64/128-bit processor, and I am told that the design specification calls for it to run at 100 MHz (about 12 times faster than the Mac Plus). Unfortunately it will probably be 2 years before completion but then, who knows?

The 68040 didn’t quite live up to these rumours! Released in 1990, the ‘040 was a 32-bit processor running at 25 MHz, with later models topping out at 40 MHz. Apple used the ‘040 in the Quadra line.

68040 die photographed by Pauli Rautakorpi under CC BY 3.0

68040 die photographed by Pauli Rautakorpi under CC BY 3.0

The Real Cost of Software

Continuing from What’s the Disk Worth (Oct ‘86), Doug Clapp considers the costs outside the box.

Last month we pegged the price of software at about $10.50 per package, give or take. Royalties, disks, manual, a box for everything; that sort of thing. Not too complicated.

And, considering you can charge…well you can charge a lot more than $10.50 for each one! Maybe $79.95? Or $125.43? Or $325.99? If you can get it, go for it! Riches. Yachts. Porsches. Groceries. But maybe not. There are a few other expenses we didn’t discuss. And “a few” is a euphemism.

First and worst (or best, depending on your point of view) is advertising. Got any idea how much advertising costs? Ever thought about it?

Let’s say you purchased a 12-insertion contract in MacUser. The price for each ad drops to $4,090. A lot less than $4,577. Still, 12 times $4,090 is $49,080. “Ohmygod that’s over ALMOST FIFTY THOUSAND DOLLARS!”

Then there’s distribution of your product. You’ve got three choices. You can sell it yourself, by mail order. Or you can sell direct to dealers. Or you can sell to distributors, and let them sell to dealers. Or you can do some combination of the three.

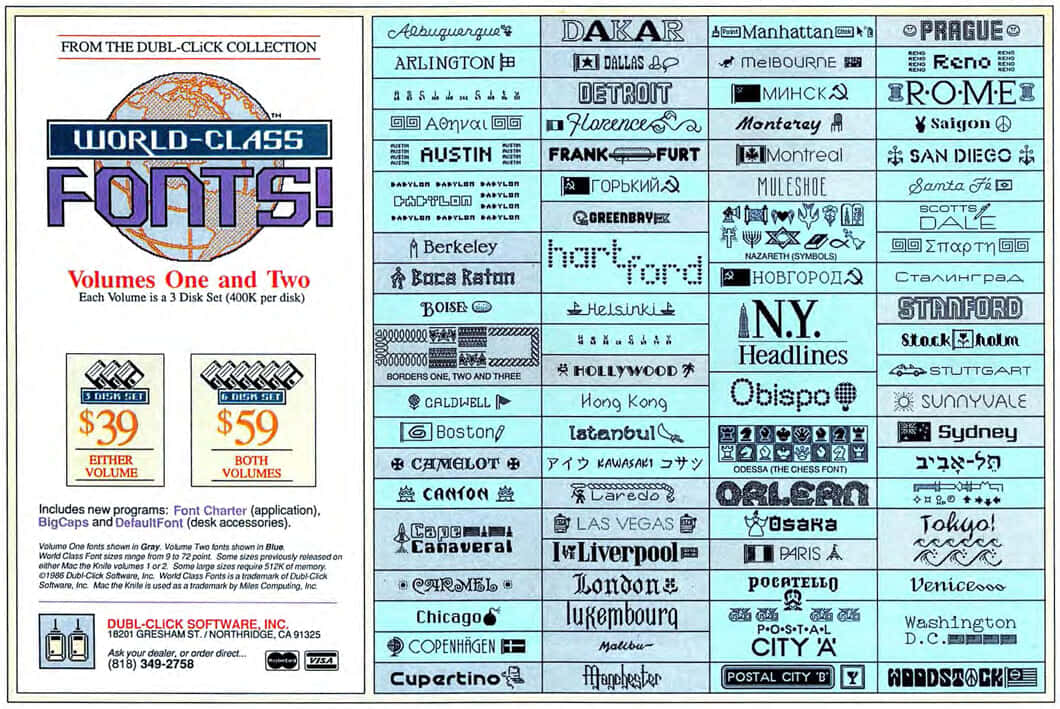

World Class Fonts

On page 48, there are “world-class” fonts for almost every city.

If you’re a typography fan, check out Fluent Fonts (Oct ‘85) and Adobe System Type Library (Sep ‘86).

MazeWars+

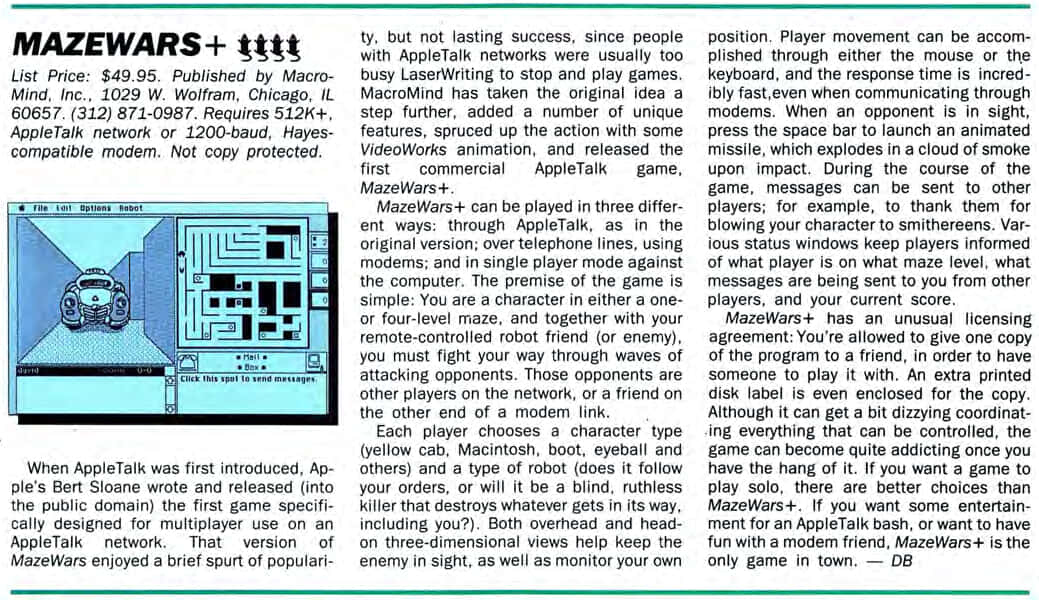

MazeWars returns with a plus on page 51.

MazeWars+ can be played in three different ways: through AppleTalk, as in the original version; over telephone lines, using modems; and in single player mode against the computer. The premise of the game is simple: You are a character in either a one- or four-level maze, and together with your remote-controlled robot friend (or enemy), you must fight your way through waves of attacking opponents. Those opponents are other players on the network, or a friend on the other end of a modem link.

MazeWars+ has an unusual licensing agreement: You’re allowed to give one copy of the program to a friend, in order to have someone to play it with. An extra printed disk label is even enclosed for the copy.

If you want a game to play solo, there are better choices than MazeWars+. If you want some entertainment for an AppleTalk bash, or want to have fun with a modem friend, MazeWars+ is the only game in town.

Read more about the original MazeWars in Beyond the LaserWriter (Mar ‘86).

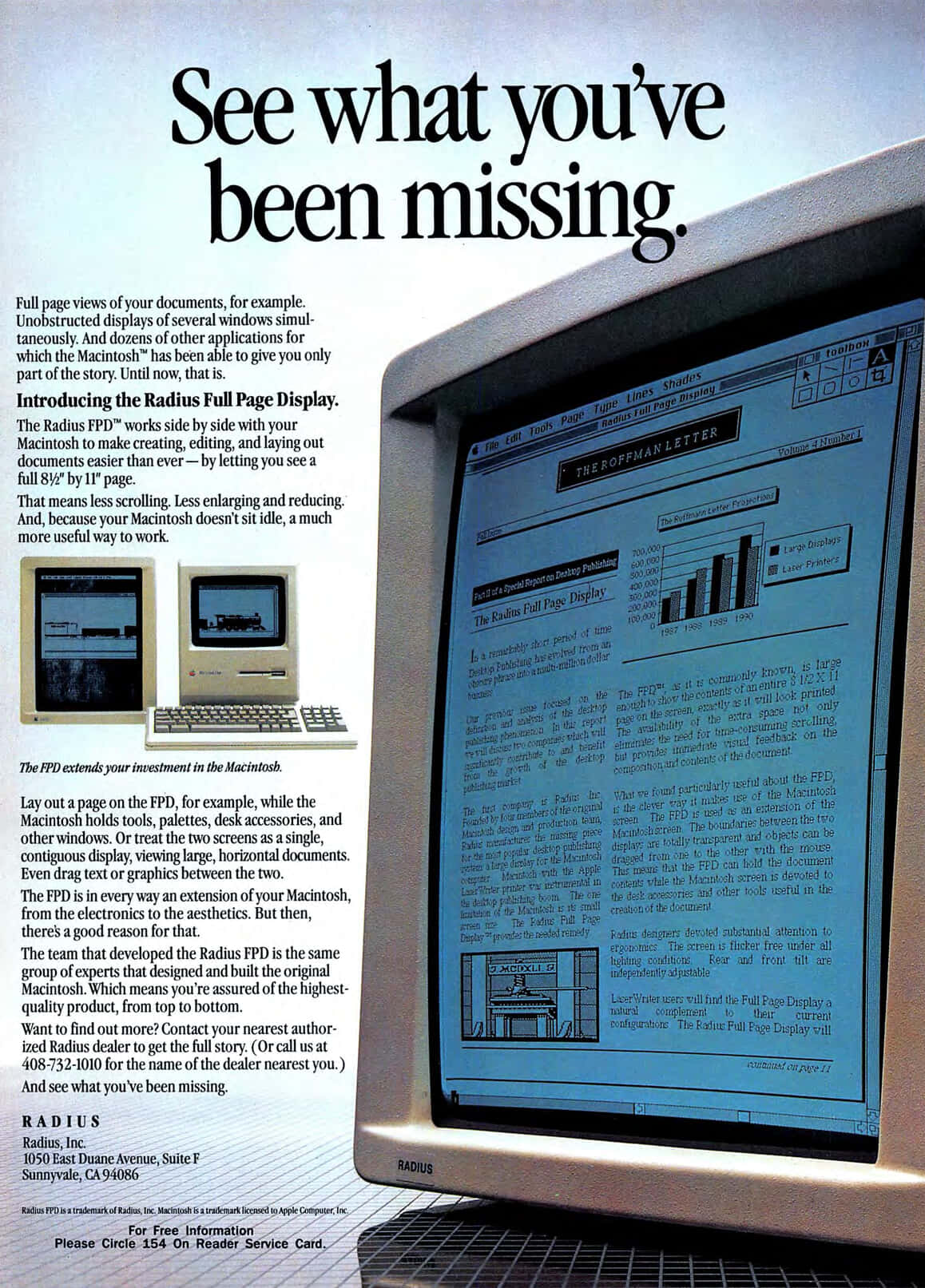

The Big Picture

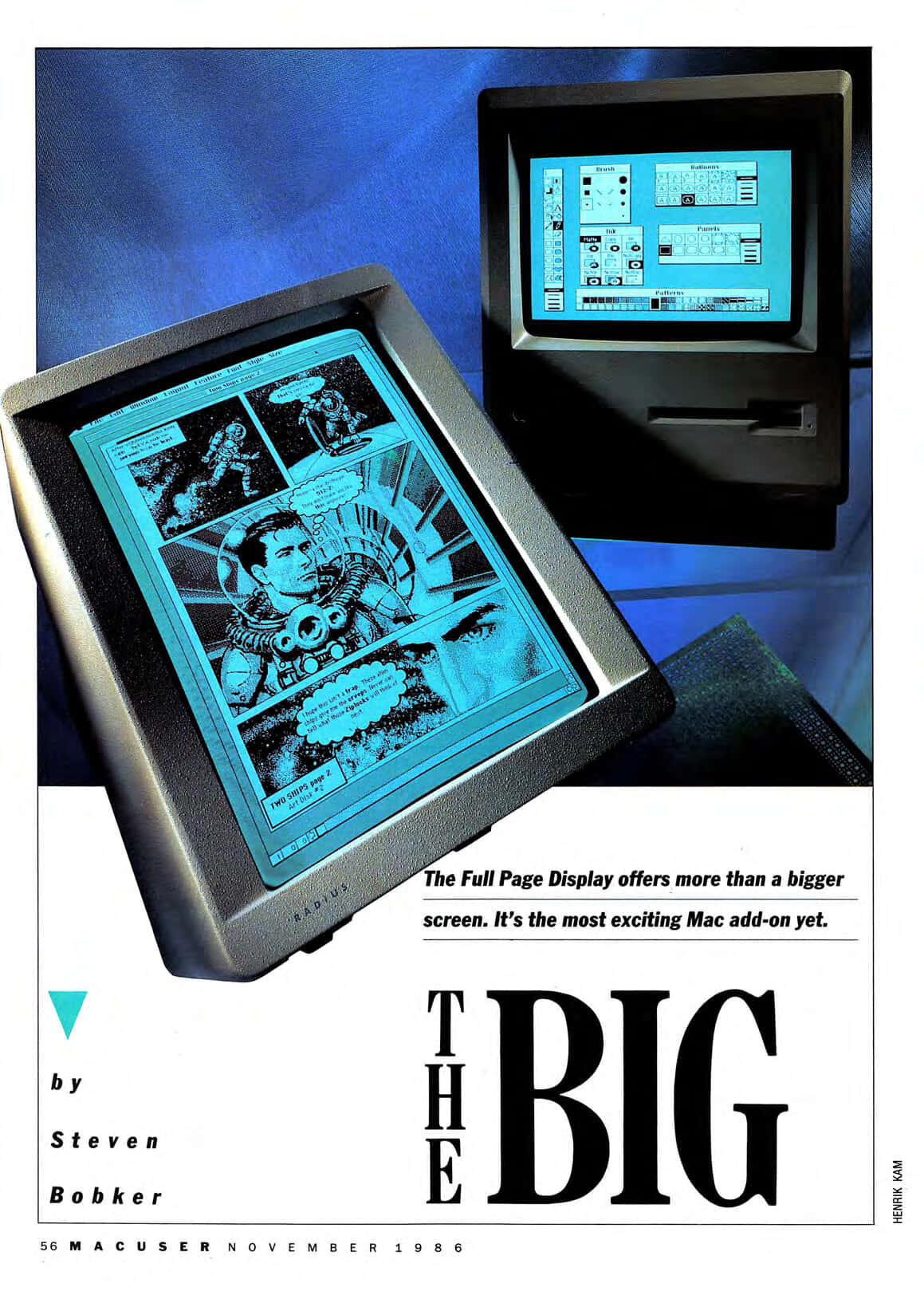

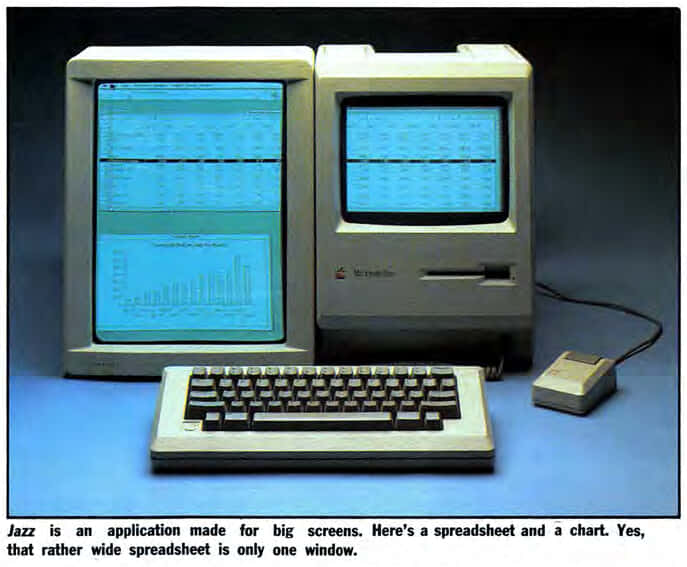

This month’s big story is Radius’ Full Page Display (FPD) on page 56.

One of the most persistent criticisms of the Macintosh has been that its screen is too small. Of course, those of us who actually had and used Macs knew differently. The screen was just fine, and anyone who said otherwise was just a stuffy old IBM user… It turns out the critics were not entirely wrong. A big screen does make a big difference in usability.

Burrell’s Wizardry

The FPD places a box just slightly larger than the Mac to either the left (preferred) or right side of the Mac. It connects to the Mac via a shielded cable that exits the Mac through a connector that’s mounted in the security slot. The Mac that is the master unit has to be modified by Radius also.

What you get is a new screen that can show a whole printed page. It’s 640 pixels wide by 864 pixels deep. While a normal Mac has a pixel density of 72 pixels per inch, this screen operates at a very slightly greater 75 pixels per inch. That means that its active area is just about 8.5 x 11.5 inches. And since this is a portrait mode screen (that is, the longer axis is vertical) a whole page is visible at all times.

If that was all the FPD did it would simply be another me-too large screen. However, it does much more. Its revolutionary hardware and firmware (ROM) design (by Burrell Smith and Andy Hertzfeld, respectively) not only gives this big screen a slightly higher quality than the Mac’s screen, but let’s you use the Mac’s own screen in conjunction with it. It operates as though there was no gap or space between the two physical screens. You might call the two separate screens one virtual screen. When you drag your mouse off the FPD display toward the Mac screen, it doesn’t stop. If the cursor’s position is high enough on the screen it simply moves right over to the Mac’s screen.

Andy’s Tricks

Since Andy Hertzfeld did the FPD’s programming, you wouldn’t expect run-of-the-mill results. And the code is anything but simple or staid. Andy is the programming wizard responsible for a lot of the original Mac software and firmware (including lots of the original ROM code). He’s also the genius who created Switcher, and now is working on Servant, a multitasking Finder replacement. The FPD will not only include Andy’s firmware, but also the latest available Servant.

At Your Service

What’s the big deal about Servant? Well, Andy Hertzfeld wrote it and he’s excited about it. Apple was excited enough to buy the rights to distribute it. And everyone who’s seen it has been very excited.

But that doesn’t answer the question. OK, Servant is a replacement application for the Finder. It will do everything the Finder does and a lot more. You’ll be able to have several applications running at once (multitasking). You’ll have a resource editing facility better than anything yet seen. You’ll be able to customize each individual folder and icon. And lots more.

Andy was showing and giving out version 0.79 in mid - August. That might be what the final product will look like, and knowing Andy, the release version may be very different. We’ll be keeping you informed about Servant’s progress.

Why Buy FPD?

Should the fact that the Radius Full Page Display is nearly as revolutionary and exciting as the first Macs were be a justification for spending nearly $2000 on one? No, of course not. But if you remember your first sit down session with a Mac, you’re in for more of the same with FPD. That first time is awesome.

The actual decision will have to take many factors into account. Do you use a Mac in your business? Do you regularly do page layout or other large graphics-intensive work? Do you find yourself often scrolling long distances, or needing wider spreadsheets, or bigger charts? Then the FPD may be for you. The added productivity that will result will cover its cost in a short time.

Radius has an advert on page 20 that provides a nice closeup of the screen.

Radius has an advert on page 20 that provides a nice closeup of the screen.

For a contemporary perspective on the Full Page Display, visit 32by32, or watch a demo from The Computer Chronicles (begins at 12m04):

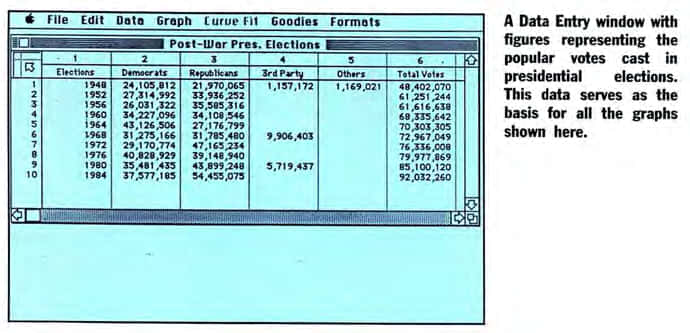

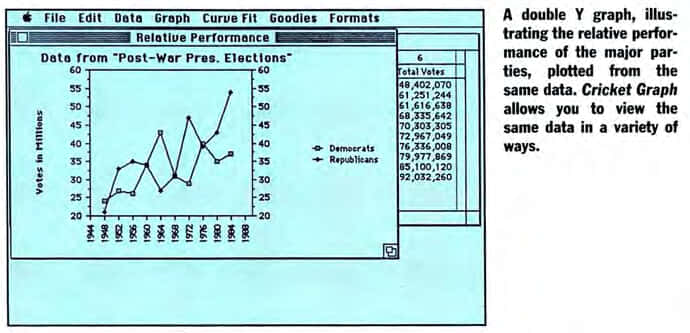

Dissecting Cricket Graph

Drawing conclusions is easier with good charts on page 82.

Everyone knows the shortcomings of “raw” data. Disorganized collections of facts and figures may contain a lot of useful information, but it’s hidden by its surroundings. Even after data has been “cooked” for many hours over the low fires of a spreadsheet, its meaning may still be obscured.

Cricket Graph Science and Business Graphics is both an excellent graph and chart generator and a useful data analyst. Cricket Graph can accept data directly entered via the keyboard, or imported from a spreadsheet or data base.

Cricket Graph requires a 512K or larger Mac. Both disks are needed to get started, so a two-drive system is essential. On a Mac Plus or on an Enhanced or upgraded 512K Mac with 800K drives, you can simplify the issue by transferring all the files on to one disk.

Twelve graphing and charting possibilities are available. You’ll find the common bar, line, column and pie charts, as well as the less common scatter, area, stacked bar, stacked column, polar, double Y, and quality control (QC) charts.

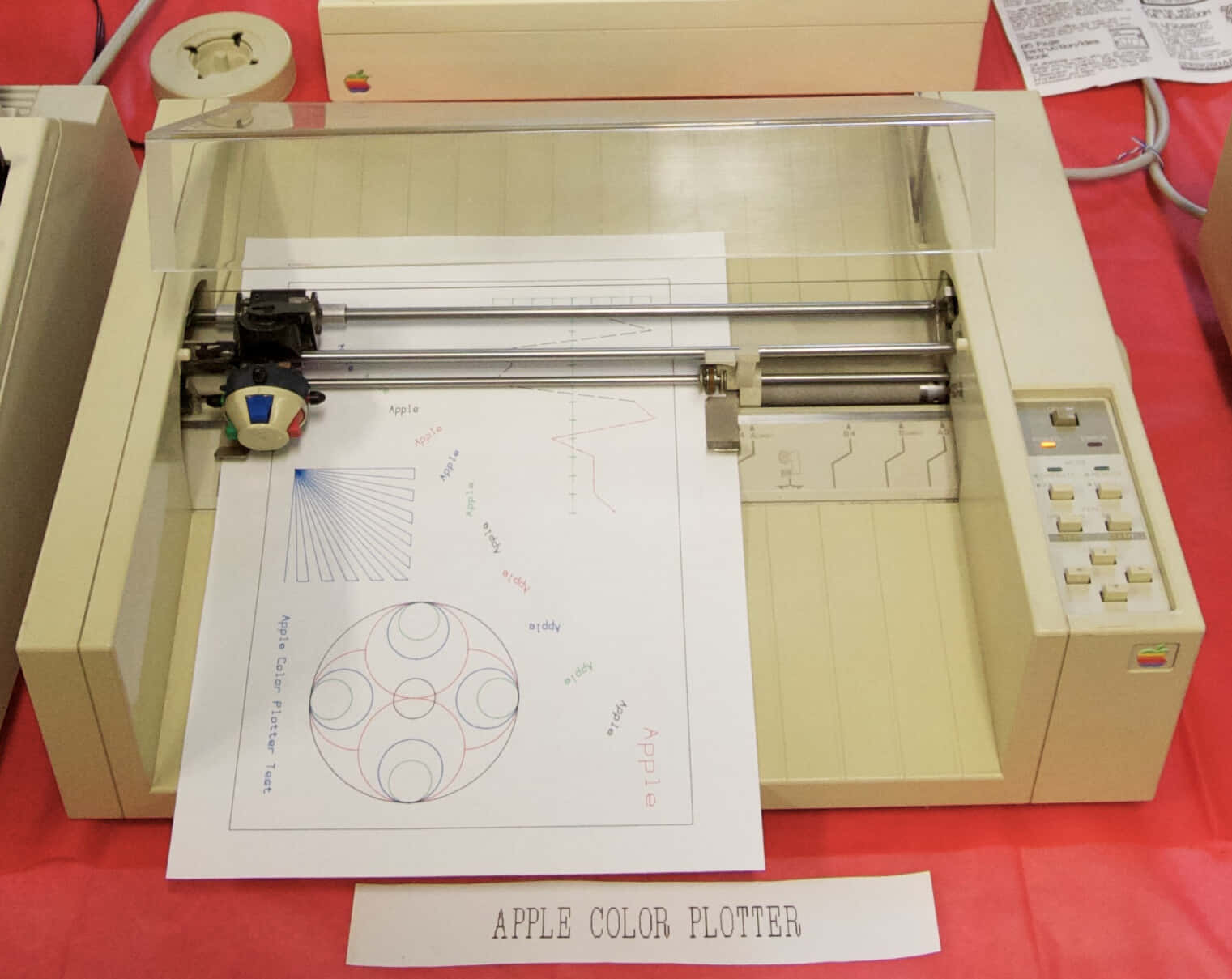

Along with the ImageWriter, Cricket Graph supports a number of popular plotters. Drivers for the Apple Color Plotter and for the Hewlett Packard 7470A, 7475A, 7550A, and Color Pro, are included.

Apple Color Plotter photo by Marcin Wichary under CC BY 2.0

Apple Color Plotter photo by Marcin Wichary under CC BY 2.0

Of course, Cricket Graph is not a spreadsheet. Nor is it a statistical analysis package. It is first and foremost a tool for creating graphics. But the integration of excellent graphics with competent visual and numerical analytical capabilities makes for a powerful combination. With Cricket Graph you might find yourself drawing conclusions with greater insight and perspective.

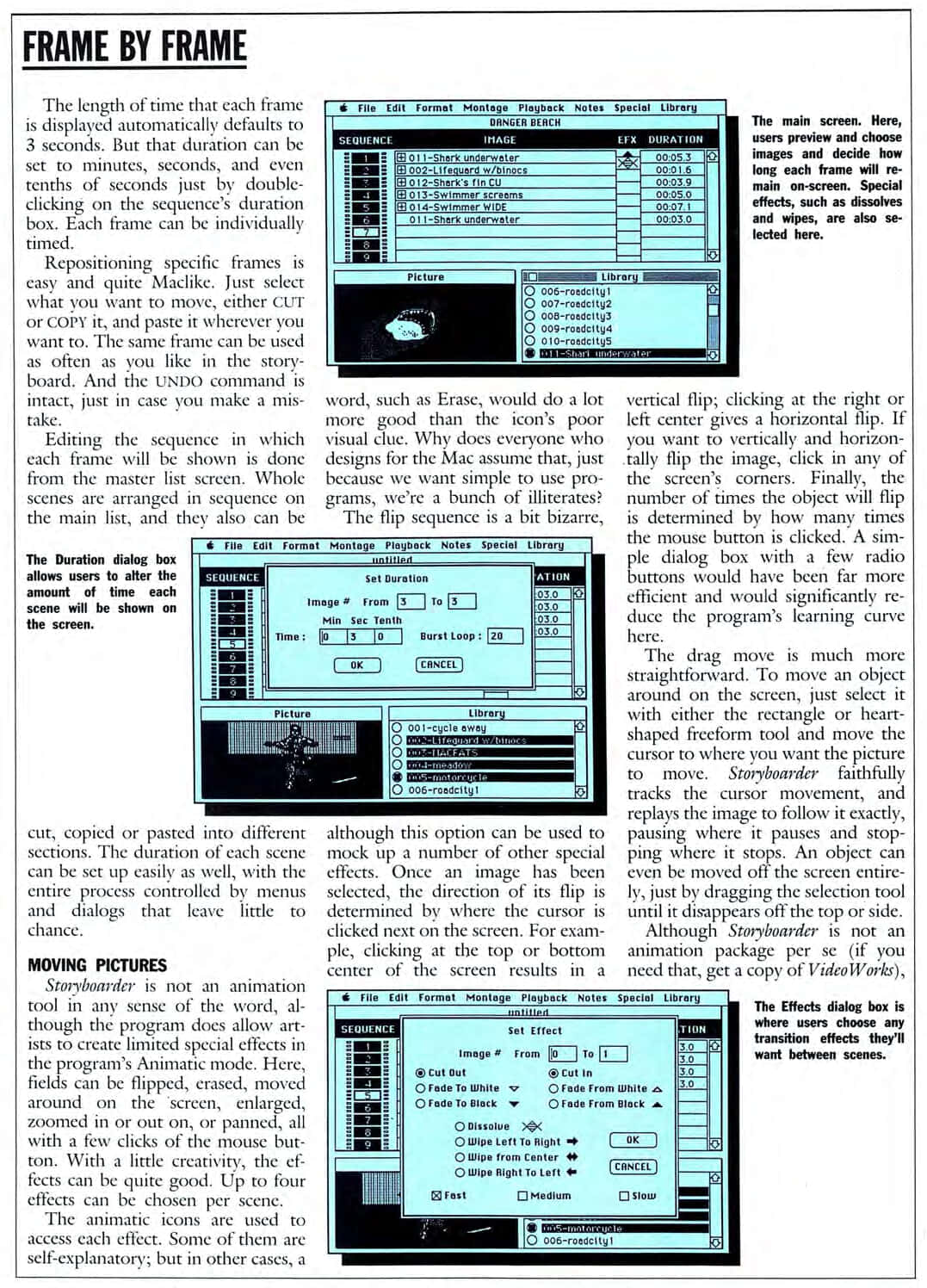

Storyboarder

Create a storyboard for your next blockbuster (page 88).

Hitchcock did it. Spielberg still does it. And so does anyone who works with film or video production… Storyboards are to visual media what outlines are to written words — a rough draft of what the finished product will look like.

Now, with the help of a program called Storyboarer, the Mac’s potential for creating and modifying storyboards is realized. Add the fact that Storyboard accepts MacPaint pictures (or any documents saved in PICT format) and the combination is nearly irresistable.

Storyboarder is not an animation tool in any sense of the word, although the program docs allow artists to create limited special effects in the program’s Animatic mode. Here, fields can be flipped, erased, moved around on the screen, enlarged, zoomed in or out on, or panned, all with a few clicks of the mouse button. With a little creativity, the effects can be quite good. Up to four effects can be chosen per scene.

Storyboarder is the first of an anticipated MacFats series meant for television and film industry users. If American Intelliware can work out the few bugs, Storyboarder is an indication that the series could just help those of us who work with both words and pictures.

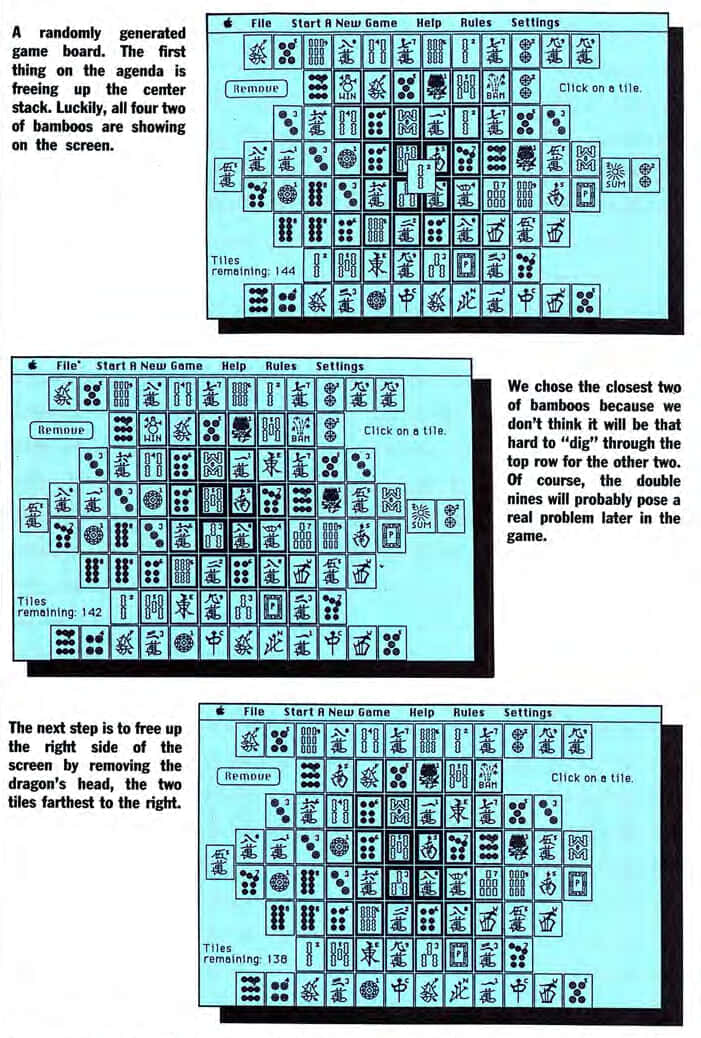

Shanghai Surprise

Defeat the dragon by skill alone (page 110).

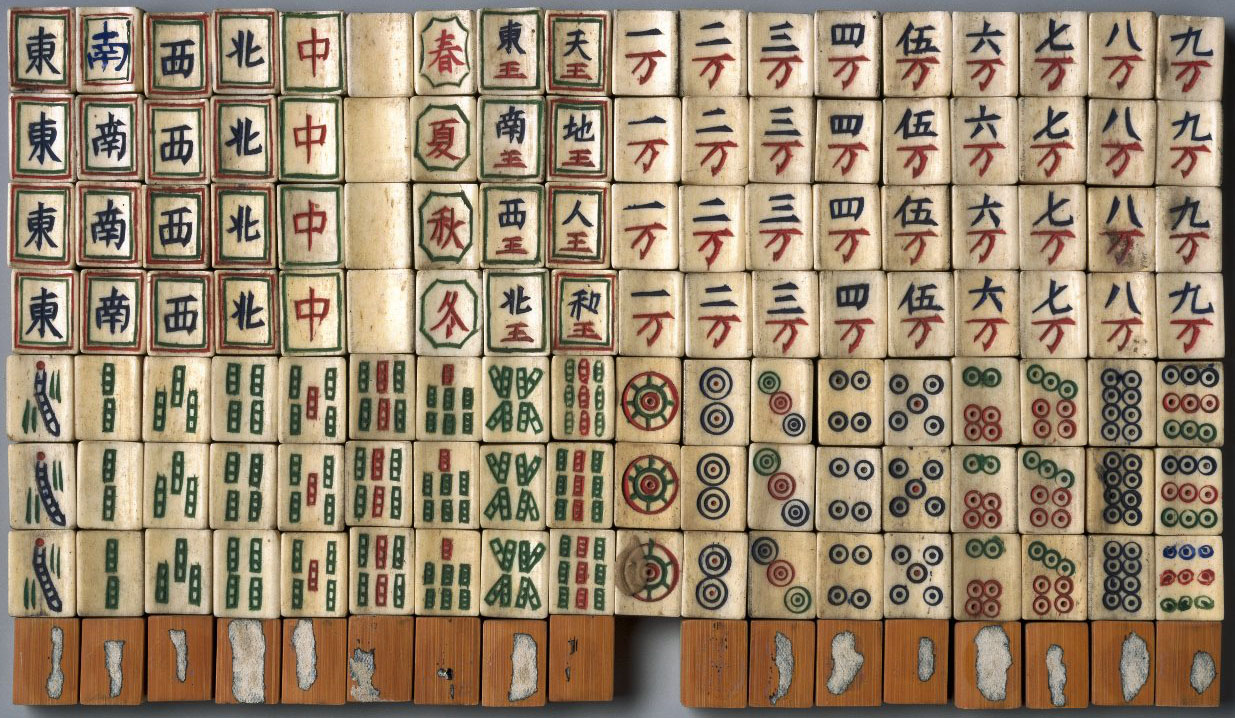

Activision’s new strategy game is just full of surprises. Surprise Number One is that it uses mah-jongg tiles. That’s right — mah-jongg. The most popular housewives’ game since canasta. Surprise Number Two is that, although it looks a lot like mahjongg, get just below the surface and you’ll realize Shanghai is a completely different game. But the real surprise about Shanghai is just how addictive a solitaire game can be.

The object of Shanghai is to clear the game board of all its 144 tiles, two by two. Simply choose exact matches and remove them from the board.

Not necessarily. If there were only two of each type of tile, things would be pretty straightforward. But there are four tiles to each set. And when the game begins, quite a few of these tiles are hidden in stacks.

Real strategy comes into play in choosing which tiles to remove, and when. For example, it may not make sense to remove a particular set of matching tiles when you can see three out of the set of four. That’s because you never know where the fourth matching tile will show up, and take a chance on trapping it, possibly under its own exact match, unless you try to figure out your strategy logically.

Mahjong Tiles photograph courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum under CC BY 3.0

Mahjong Tiles photograph courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum under CC BY 3.0

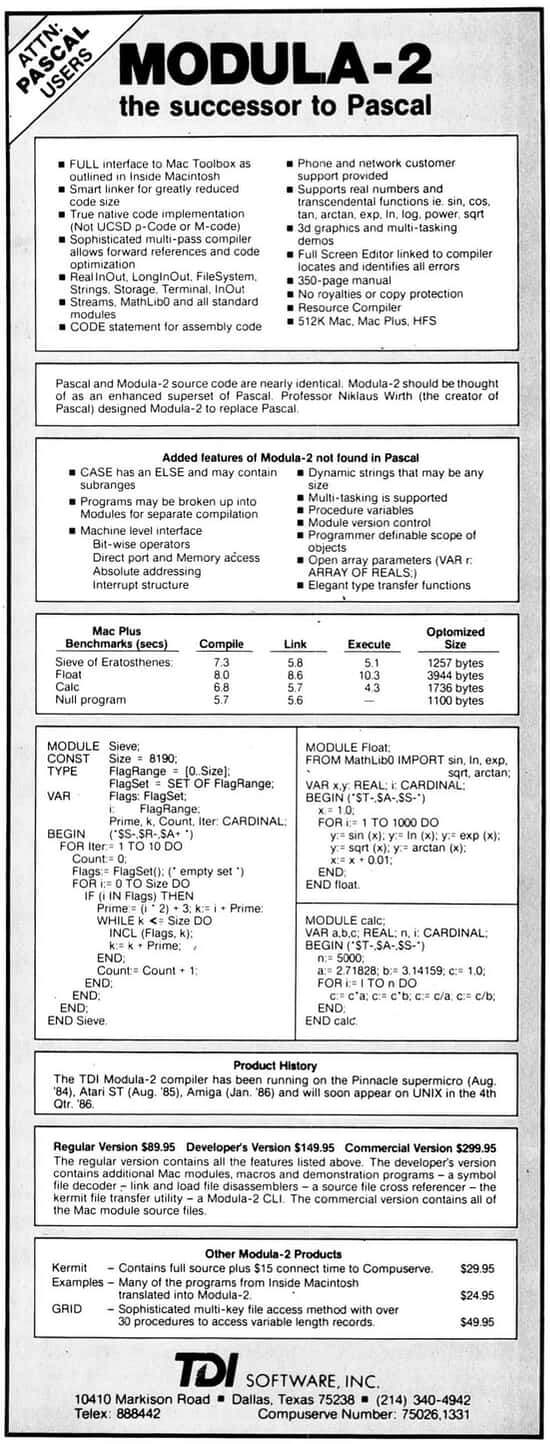

The Successor to Pascal

We began with an advert for (Turbo) Pascal and finish with an advert for its successor, Modula-2, that includes source code (page 174).

Modula-2 is on the cover of Byte August 1984 (archive.org), while inside, Niklaus Wirth discusses its history and goals on page 145. Wirth also led the group that developed the Lilith Workstation (Wikipedia) using Modula-2:

The development of Lilith was influenced by the Xerox Alto from the Xerox PARC (1973) where Niklaus Wirth spent a sabbatical from 1976 to 1977.

The influence of Xerox PARC is felt yet again.

Niklaus Wirth was a giant of software design who died in 2024. The Register has an excellent obituary: RIP: Software design pioneer and Pascal creator Niklaus Wirth.

The modern software industry has signally failed to learn from him. Although he has left us, his work still has much more to teach.

Other Features and Reviews

- The Money’s in the Works: financial functions in MS Works (page 60)

- Covering dBASES: dMAC III brings dBASE III to Mac (page 68)

- Bringing PageMaker to Life: get to grips with the doyen of DTP (page 74)

- Let’s Talk Telecommunications: a friendly guide (page 96)

- Up and Away: Flight Simulator and Orbiter reviewed (page 100)

- Pascal Programming Series, Part 4 (page 118) - started Jul ‘86

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 86.12 travels to December 1986. We get colourful with the Apple IIGS, watch Apple adverts with Roger Ebert, build a network with PhoneNET, run an email server from a floppy disk, and rage against poor service from Apple dealers. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏