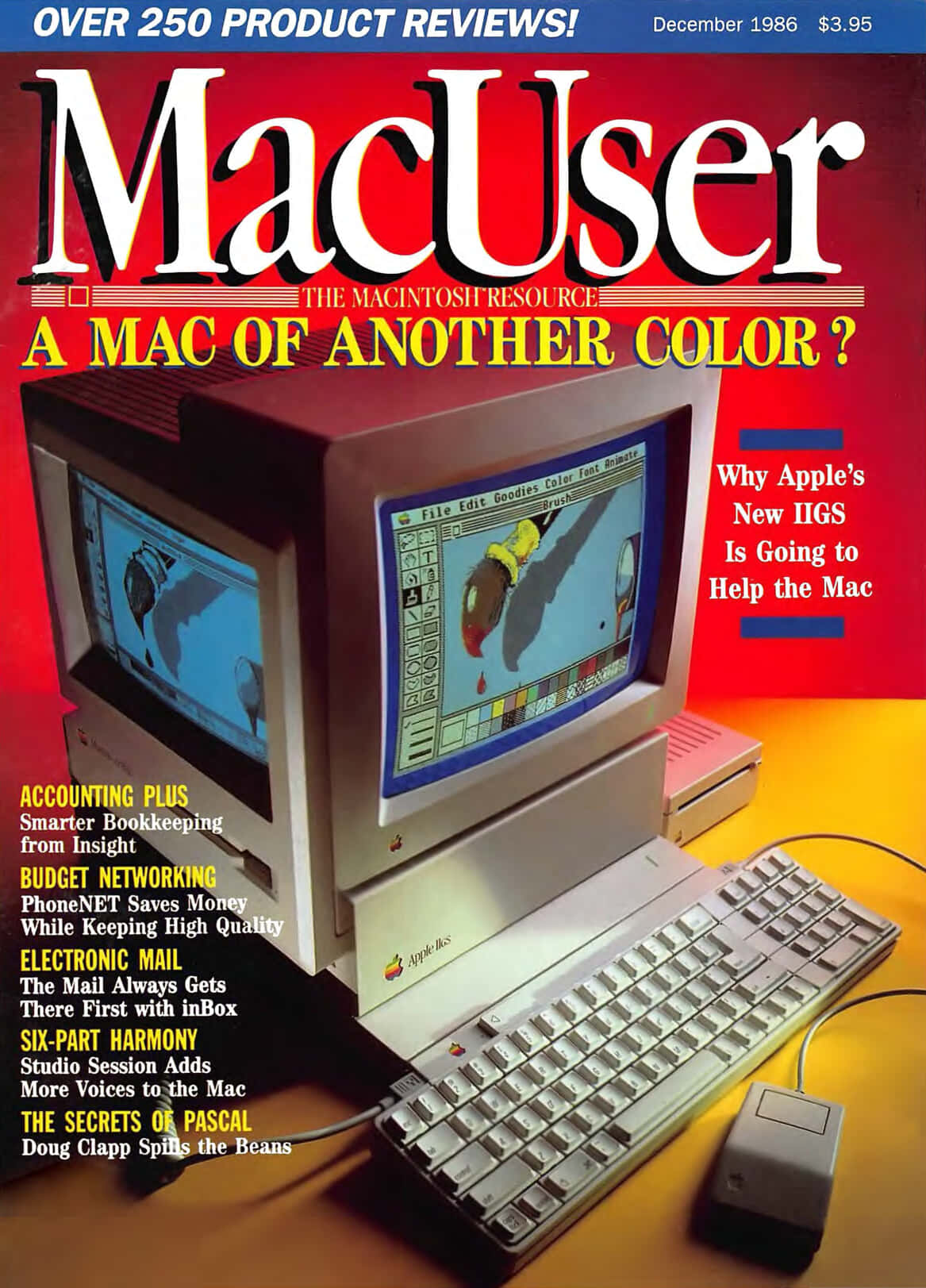

Mac History 86.12 - Apple IIGS and PhoneNET

This month we get colourful with the Apple IIGS, watch Apple adverts with Roger Ebert, build a network with PhoneNET, run an email server from a floppy disk, and rage against poor service from Apple dealers.

This is A Macintosh History: a history of the early Apple Mac told through the pages of MacUser magazine. This post is based on the December 1986 issue. New to the series? Start at the beginning with Welcome to Macintosh (Oct ‘85).

December 1986

Pick up your copy of MacUser December 1986 from the Internet Archive. Download 68K Mac software from Macintosh Garden and Macintosh Repository.

How’s Your Dealer?

In 1986, buying a Macintosh direct was impossible: you had to go to a dealer. Neil Shapiro has some choice words for Apple dealers on page 19.

A few days ago I angrily walked out of an Apple dealership, as I have done many times before. This time I have come to a conclusion: I will never return to an Apple dealer to buy anything that I can just as easily mail-order, unless Apple changes many of the policies and procedures associated with their dealer network.

One dealer attempted to charge me $120 in labor for running a RAM test because it took 3 hours. (Of course, it was just the machine doing the work; you start the test, go away and come back at least 3 hours later to check the results on the screen.)

Then there was the time I had with the new modem cable. I had just purchased an Apple modem secondhand from a friend. It came without a cable. So, I went to one dealer who said that they didn’t have it in stock. By the sixth dealer I was smelling a rat. Sure enough, the dealer inadvertently revealed that he didn’t have cables to sell separately in stock. It turned out that if I did not buy my modem from him I was not entitled to purchase a cable. He simply refused to sell me a cable as he had six modems and six cables (packaged separately, each with its own parts number and each listed as a separate retail item).

Take a look at the 1987 Apple Personal Modem brochure (PDF on apple.asimov.net), including a choice of cables.

Letter of the Month

Tired of wall-to-wall DTP coverage? Sue Gelinas of Culver City certainly is (page 30):

I don’t know if I represent a large percentage of the Mac community, but I know this: I am really sick of hearing about desktop publishing. If desktop publishing is one thing the Mac does particularly well, fine. But the press seems to have snatched it up like a terrier snatches a rat and is determined to shake every last word our of it that can possibly be written.

All desktop publishing does is encourage people with very little to say to write enough so they can fold one page over, or make it a four-pager and distribute it with mail merge to innocent victims. Who really needs it? Who is making all these newsletters? More important, who is reading them? Please spare us any more on desktop publishing.

New on the Menu

Mac on the Tube

Apple has new TV commercials created by BBD&O (page 42).

There are a grand total of 11 and by far the best of the lot (in this writer’s humble opinion) are the Macintosh series of corporate minidramas. At the press luncheon unveiling the new advertising in October, Apple asked film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (At the Movies) to do their stuff.

Watch Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert discuss two of the ads in 1986:

"…and a budding genius will be found where once a face was seen, but not heard…"

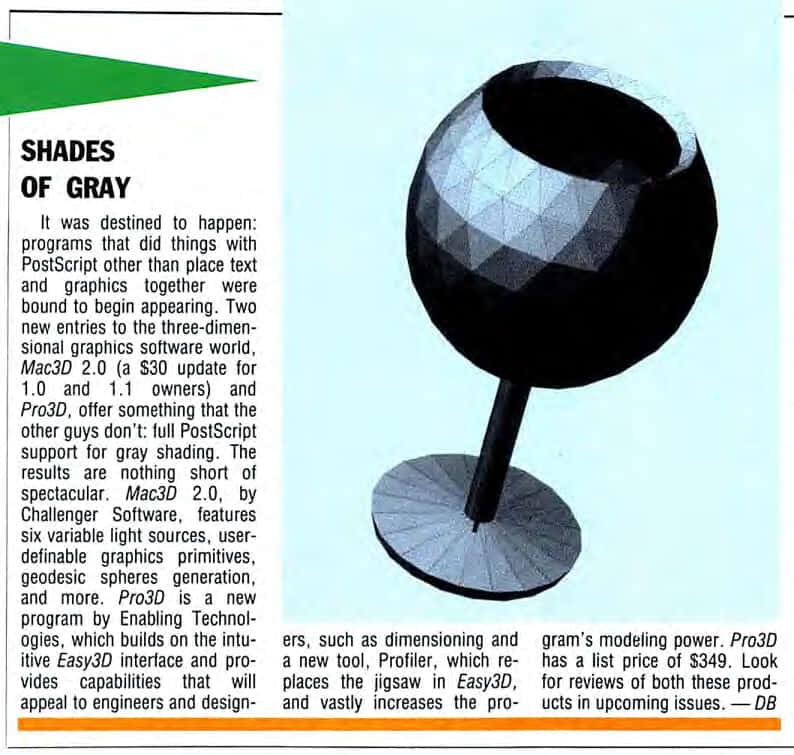

Shades of Gray

Grey shading comes to Postscript on page 49:

It was destined to happen: programs that did things with Postscript other than place text and graphics together were bound to begin appearing. Two new entries to the three-dimensional graphics software world, Mac3D 2.0 (a $30 update for 1.0 and 1.1 owners) and Pro3D, offer something that the other guys don’t: full Postscript support for gray shading. The results are nothing short of spectacular.

Read a quick review of Mac3D 2.0 (Jan ‘87).

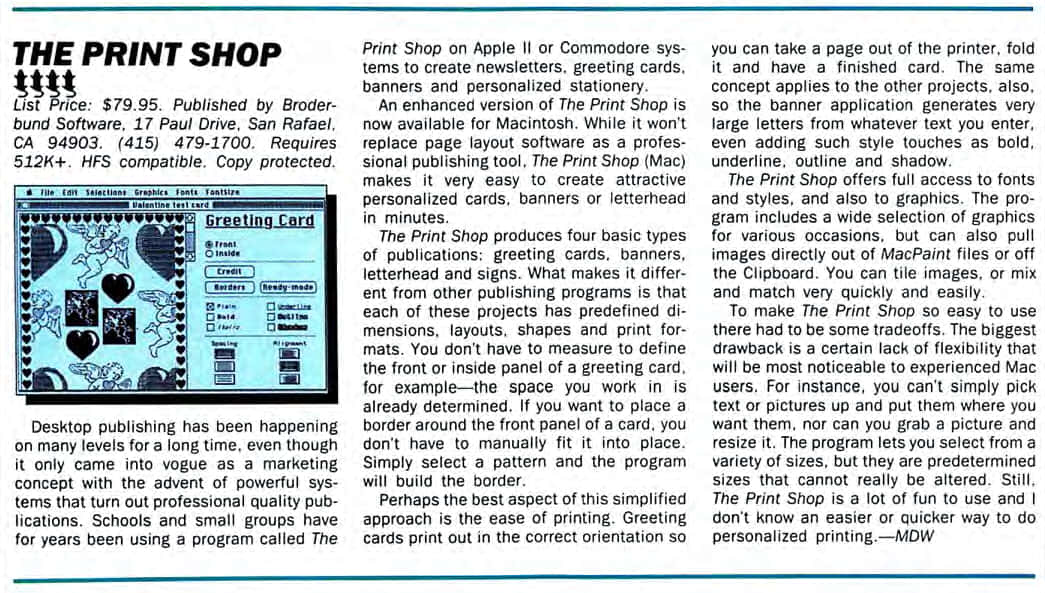

The Print Shop

Desktop publishing is far from new in The Print Shop (page 73).

Desktop publishing has been happening on many levels for a long time, even though it only came into vogue as a marketing concept with the advent of powerful systems that turn out professional quality publications. Schools and small groups have for years been using a program called The Print Shop on Apple II or Commodore systems to create newsletters, greeting cards, banners and personalized stationery.

The Apple II Age by Laine Nooney dedicates a chapter to the origin of The Print Shop.

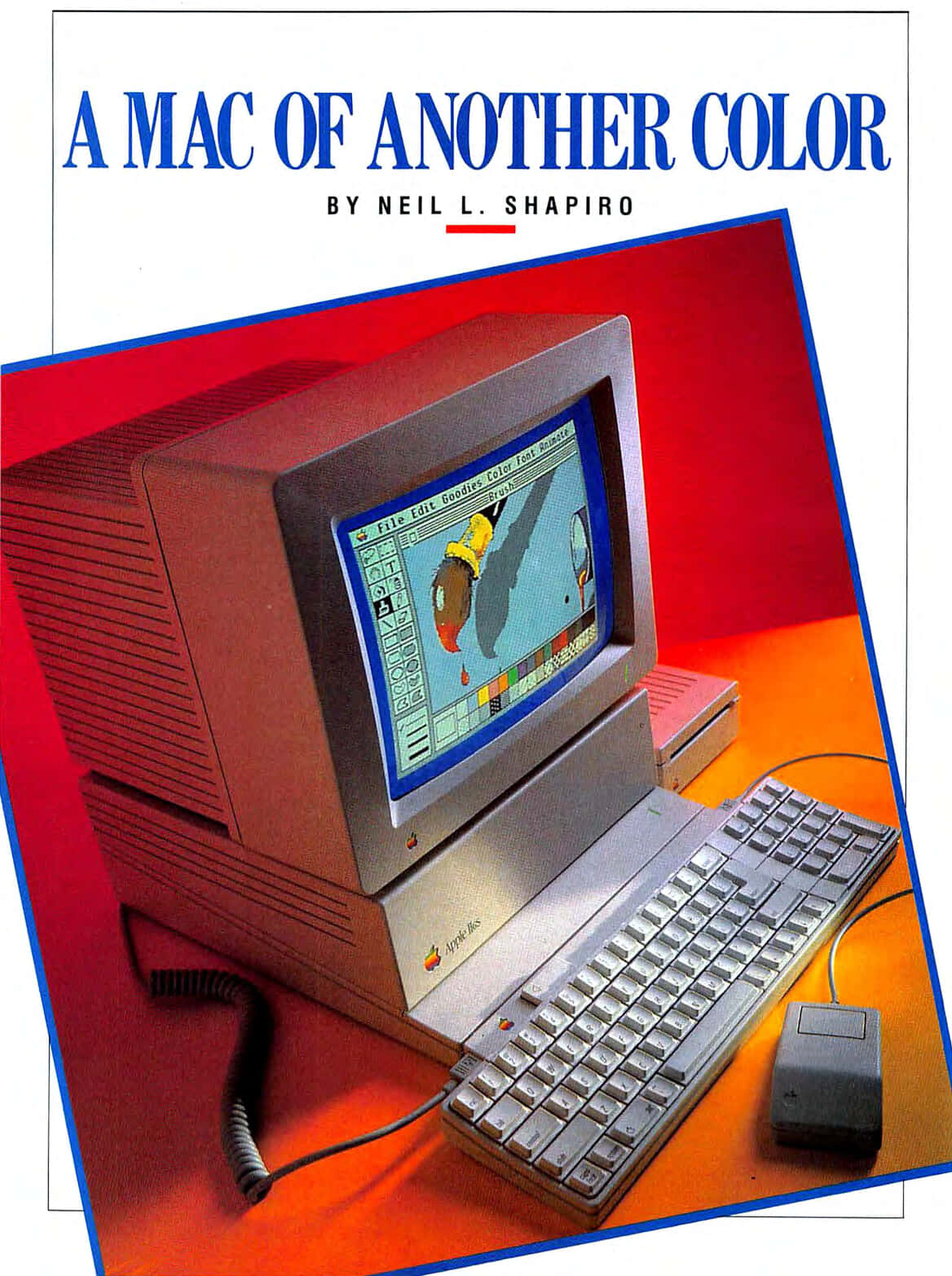

A Mac of Another Color

In late 1986, Apple launched a new colour computer, but it wasn’t a Macintosh. Turn to page 84 to meet the Apple IIGS.

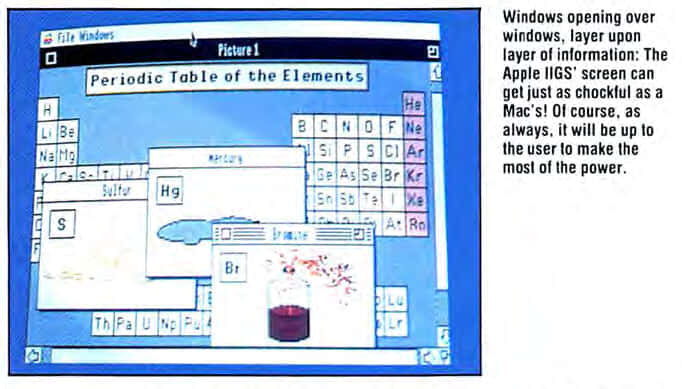

I moved a window around onscreen, resized it, played a bit with the scroll bars and then moused up to the menu bar. I clicked on the Color menu and pulled it down. Displayed were 16 different colors, each one a solid bar of color right across the menu space — looking for all the world like those bright chiclets of color pigments in a child’s watercolor set.

I was using Apple’s newest computer, the Apple IIGS. This latest addition to the Apple II family of computers features a 16-bit processor, color graphics, and the capability for a Mac-like interface style of programming and program design.

All the units are in a new color that Apple calls “platinum” but which my mother taught me to call “light gray.” But by any name it is a handsome, high-tech color.

Then you swing up the top of the system unit and look at the motherboard you see seven IO slots, much like in the Apple IIe.

Before we lower the hood and look at the screen display we do need to examine one chip in depth. It’s called the DOC chip which stands for “Digital Oscillator Chip.” It’s the one with the name “Ensoniq” emblazoned on top. The Ensoniq Corporation is very famous in the world of music for its digital synthesizing devices and equipment. This particular chip contains 32 oscillators for up to 15 voices. It also has “sampling” ability so that a circuit could be offered to record sounds or voices to be played back and modified by the chip’s ability to work on waveforms.

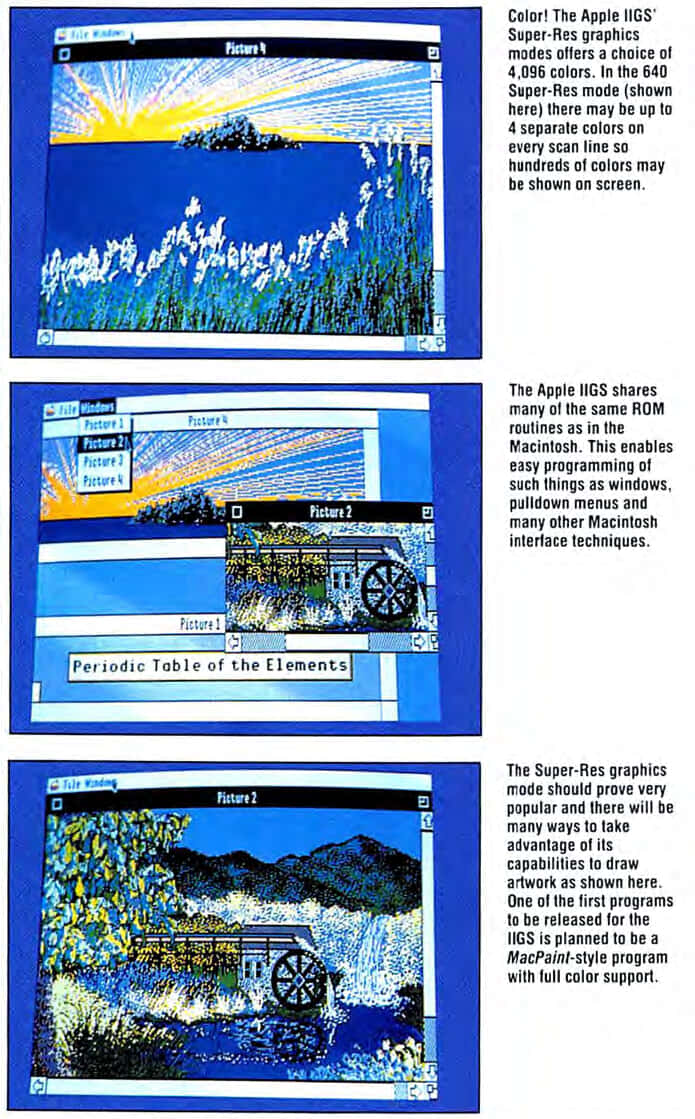

The Apple IIGS shares all of the three graphic modes possible in earlier Apple lls. Lo-Res (40 X 40, 16 colors), High-Res (260 X 192, 6 colors) and Double-Res (560 X 192, 16 colors) are all fully supported. To this the Apple IIGS adds Super-Res graphics, which, itself is available in two “flavors.” The 320 Super-Res graphics (320x200) may access 4096 colors with up to 16 of those colors appearing on each scan line. The 640 Super-Res graphics (640x200) may also access from a choice of of 4096 colors but with only 4 colors appearing on each scan line.

Now that the Apple IIGS has been released it is clear that Apple Computer should be able to hold onto, and even expand, their complete market share of the personal computing field. Beyond that, the way the two machines complement each other is truly an interesting topic. Keep in mind the similarities in the Toolbox calls and programmability.

The Apple IIGS is a big jump over the IIe, but pricey at $999 ($2,000 in 20201).

Byte October 1986 (archive.org) provides an alternative perspective:

The Apple II GS hog-tied by Apple II compatibility, approaches but does not match or exceed current microcomputer capabilities. The 8086-like segmented memory of the 65C816 is not as elegant as that of the 68000, used in the Apple Macintosh, the Commodore Amiga, and the Atari 520ST. In addition, the 65C816 lacks the hardware multiply and divide instructions available in both the 8086 and the 68000 processors. The Apple II GS’s graphics, though now competitive, do not offer any advantages over the Amiga’s or the Atari ST’s, nor is its price competitive with either. Its only clear superiority is in its sound capabilities, which for many buyers will not outweigh graphics and price.

Apple II Books

For a deeper look into the Apple II, I can recommend two very different books:

- Sophistication & Simplicity: The Life & Times of the Apple II by Steven Weyhrich

- The Apple II Age: How the Computer Became Personal by Laine Nooney

The Electronic Postman

InBox brings sophisticated mail to the Macintosh on page 100. Email may be a chore in the 2020s, but it was an exciting new application in 1986.

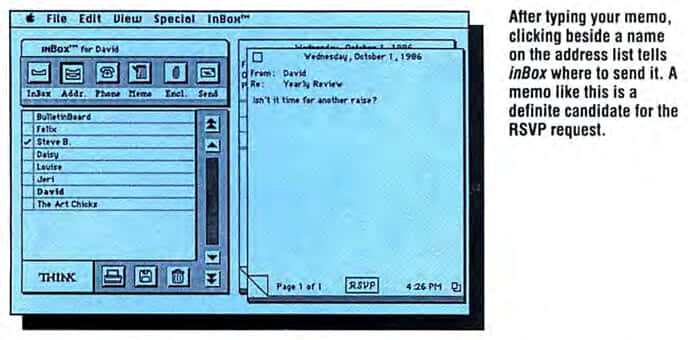

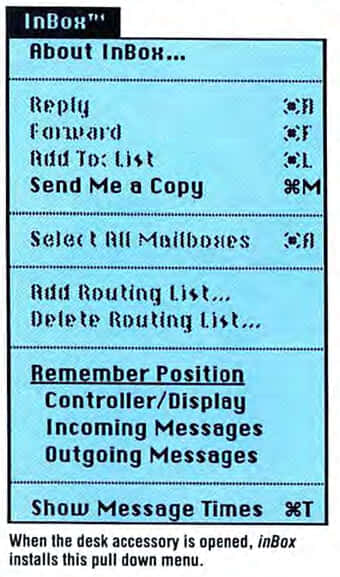

InBox allows any user to send memos, documents, and even entire application programs to anyone on an AppleTalk network who also has inBox installed.

The most powerful feature of inBox is that you can send mail whether or not the addressee is logged onto the system… And therein lies the one potential problem with inBox for some Mac offices: in order to keep track of items being sent to individuals not on the system, you must dedicate a single Mac with at least 512K of memory to function as the inBox file server.

You then create a file called inBox Data, where all the message activity will reside. (If you anticipate that one 800K drive with System, Finder and 350K for inBox itself, 6K per mailbox and 1K for every two short messages may provide enough storage room for your messages, a floppy system will work for you; otherwise, a hard disk will be essential.)

Clicking the Memo icon brings up an electronic memo pad, with the date, time and your name already filled in… Memos can be as long as 30 pages. If you need to enclose a file, a spreadsheet, a MacPaint document, indeed anything you’ve created on the Mac — you click on the Paper Clip icon, and up comes a dialog box that allows you to click through disks and scroll through files.

After using inBox for two months, I can unequivocally say that it has vastly improved the communications process within my organization and has made it even more clear that the Macintosh office is becoming more and more capable of serving the needs of business.

Party Line

PhoneNET offers a new way to connect Macs to AppleTalk on page 106.

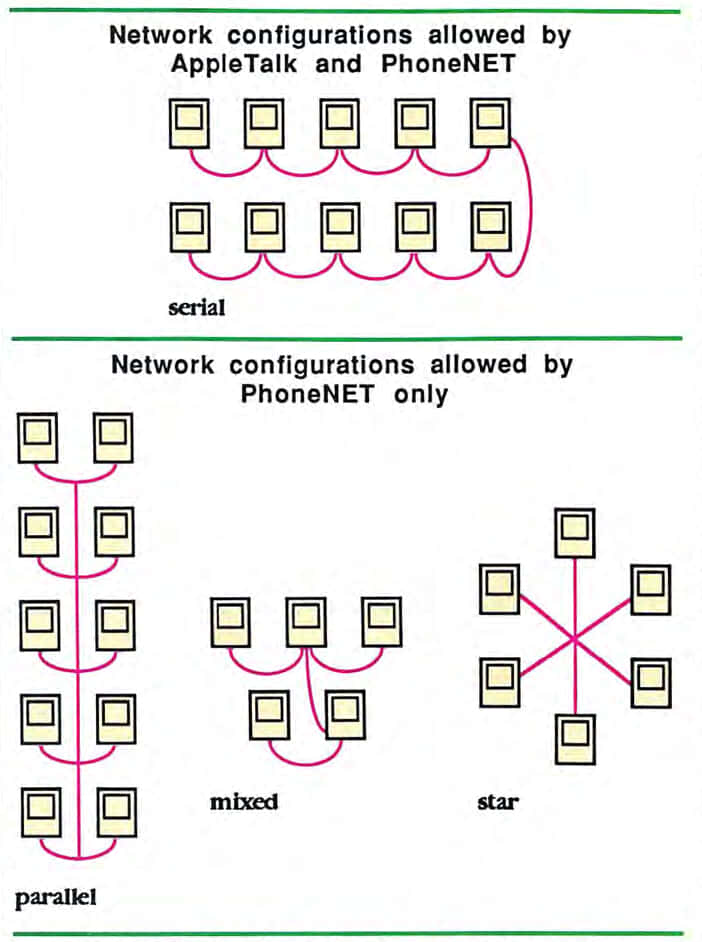

The simplicity and power of AppleTalk have changed how people think about local area networks. But before you install a new AppleTalk network or use an old one for much longer, take a look at PhoneNET. It’s fully AppleTalk-compatible and offers some important advantages over using Apple connectors in every Mac network.

Many offices and homes already have all the cable they need for a network, going right where they want it, in their telephone lines. Although almost every telephone cable has four wires, only two of them (the red and green) are used for single telephone lines. The other two (yellow and black) carry no signal. Now that the phone companies have decreed that you own the wiring within your office or home, you are free to run whatever you like through the extra pair of wires. PhoneNET lets you plug in a phone cable connector from your wall jack to your Mac with no charge for buying or installing cable.

Because PhoneNET operates more like a digital phone network than a linear data network, it allows you to set up your wiring in stars and branches. The only limitation is that you may not create loops or circles anywhere in the network.

PhoneNET and LocalTalk connectors by Bill Woodcock under CC BY-SA 4.0

PhoneNET and LocalTalk connectors by Bill Woodcock under CC BY-SA 4.0

PhoneNET uses the same RS-422 serial ports and operates at the same 230 kbits/s speed as LocalTalk. Farallon charged $49 for connectors (transceivers) in 1986. You can read the original Farallon PhoneNET User’s Guide courtesy of the Internet Archive.

See also The Seeds of AppleTalk (Mar ‘86) and check out Memories of Farallon PhoneNet (juliandunn.net), and AppleTalk, LocalTalk, and PhoneNet (lowendmac.com).

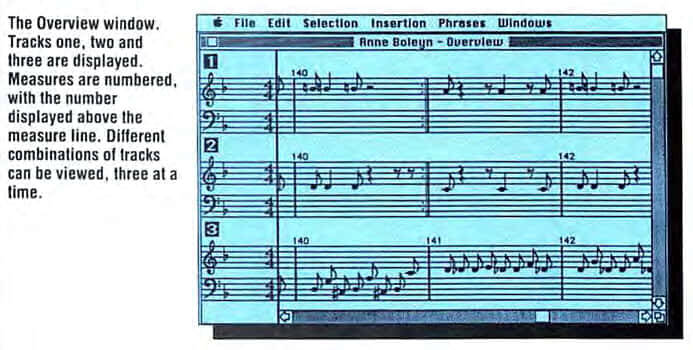

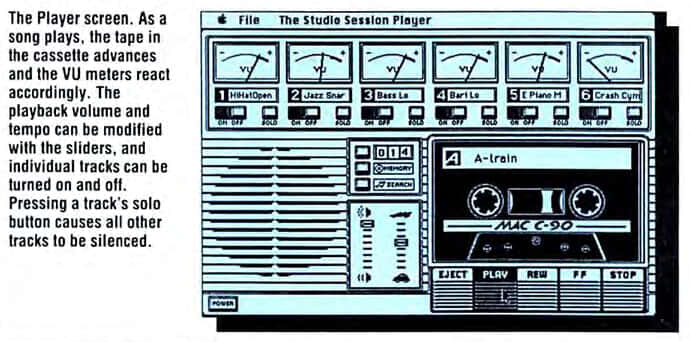

Studio Session

Sampled music comes to the Mac (page 110).

So far, Macintosh music software has been relatively good… But no matter how well the software was written, or how smoothly it worked, there was always an underlying problem that couldn’t easily be solved: the music from these programs sounds computer generated.

Enter Studio Session. This inexpensive ($79.95) program gives the average Mac musician the kind of flexibility that can be found only on multitrack sampling systems such as the FairLight CMI ($80,000+) and the Synclavier ($75,000+). Of course, these systems far outweigh Studio Session in terms of capabilities and ultimate sound quality. But they’re also priced many orders of magnitude above Studio Session, are nowhere near as easy to learn and weigh a lot more.

The premise behind Studio Session is simple: take sounds digitized from real life, get Steve Capps (of Finder fame) to help out with getting the Mac to produce six voices of sound (when it thinks it can only really handle four), create a notation-processor to type the tunes in, set to a low boil, and come up with a music program that can produce sound like no other microcomputer music package (similar software designed for the Amiga hasn’t shown up on the market yet, although it’s been promised). Even though it has some shortcomings, Studio Session is a glimpse into what music software will sound like in years to come.

Check out MIDI to the Macs (Dec ‘85) and the Fairlight CMI (Wikipedia).

ZBasic is Zmost

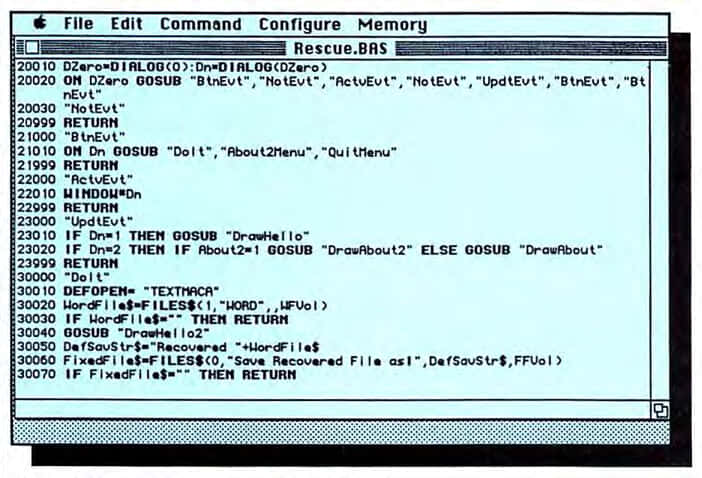

Basic joins the fast lane on page 136.

BASIC is still the language used by more programmers than any other. More people use BASIC on the Mac than C or Pascal… But until recently the programs were slow and required either that you have the full BASIC interpreter or a special non-programmable, runtime version of the language… That’s finally changed. Zedcor creators of ZBasic have released a version for the Mac.

Mac programs are generally interrupt-driven. That is, the programmer sets up the path for the program to take for events (what to do if a menu is selected or a button pushed) and then waits for some event to happen in a loop. The event-handling capabilities of ZBasic therefore are important.

If you have used MS BASIC; you will be reassured when you find that ZBasic has most of the same logical constructs. There is the familiar On Event Gosub type, for example. But ZBasic only evaluates for events at the beginning of a statement line (between the Event ON and Event OFF statements), so exactly how you state the event trapping can become important for proper evaluation by the parser.

In summary, I like ZBasic. While there are thing I would like to see it do better, the ability to generate standalone BASIC applications that use the full Mac interface is one that many people have been yearning for since the introduction of the Mac.

See also: The Great Language Face-Off (Jan ‘86) and and A Vote for MacBASIC (Jun ‘86), which explains how BASIC could have been even better on the Macintosh.

You can find an advert for ZBasic on page 197:

Adverts

We finish with two adverts. Long before ChatGPT, there was AI Prolog (page 157):

Get ready for Christmas with MacCarols (page 182):

Other Features and Reviews

- Insight accounting (page 78)

- StatView 512+ statistical analysis (page 90)

- Orbquest game review (page 118)

- Why is this game smarter than I am? (page 122)

- The Secrets of Pascal (page 128)

What’s Next?

A Macintosh History 87.01 travels to January 1987. We read Zen and the Art of the Macintosh, enter the Dungeon of Doom, seek a guru for Apple, visit Microsoft in Seattle, discover the best products of 1986, do more with MORE, put a tail on our Mac, and prep for nuclear attack. Or check out other posts from A Macintosh History.

Get in touch on Mastodon, Bluesky, or X. Enjoy my work? Please sponsor me. 🙏